The Other Lever

#86: Will the Fed achieve balance sheet normalization in 2024?

Happy Friday and Happy New Year!

I’m excited to release two lengthy reports in January - one on Bitcoin’s role in the global financial system, and another on the shifting Chinese economy and opportunities in its equity markets. But since we have spent the last several weeks discussing markets — with more to come this month — let’s briefly shift gears to monetary policy in the year ahead.

I find it somewhat fascinating, if not somewhat frustrating, how outdated the public discussion on monetary policy has become. From newspapers to FOMC pressers, one hears constantly about the role of interest rates — the traditional tool of monetary policy — but often not a word about the balance sheet — i.e. quantitative easing and tightening. And while the Fed provides years of forward guidance and qualitative explanation of its interest rate policy, it gives relatively little insight into balance sheet policy, which has remained unchanged for over 18 months.

Charitably, the lack of attention on the balance sheet is likely due to its relatively recent introduction to the central banking toolkit. We have a hundred-year history of attempting to understand how the Fed influences interest rates and how interest rates in turn influence the economy. Large-scale asset purchases (“QE”) is a new tool by comparison, introduced in the U.S. in 2008 (an emergency policy that has since become a permanent fixture). Balance sheet reduction, or quantitative tightening (“QT”), is even more recent — implemented for the first time in 2017 before ending abruptly in 2019.

There is also not a clear consensus on how balance sheet policy impacts financial markets or the economy. Some have even suggested that QE/QT does nothing at all (the “asset-swap” argument), though such arguments are unconvincing against recent experience. And it is true that the circumstances are important1. The first rounds of QE served to recapitalize the banking sector. The post-GFC QE from 2011 - 2014 offset stagnant private-sector credit growth to maintain consistent, but not excessive, growth in money supply. The most recent rounds of QE/QT since 2020 meanwhile were extreme in scale, and when tied with fiscal policy, resulted in a massive direct impact on base and broad money.

But regardless of the circumstance, we should care about the balance sheet. It’s impossible to understand modern monetary policy without it. And moving into 2024, we may see a significant shift in the path of this policy.

Inflation Volatility

In prior years, the Fed sought to influence private sector lending and borrowing through changes in interest rates policy. Lower interest rates increased demand for credit and accelerated bank lending, which in turn expanded the money supply. Today, the Fed still controls interest rates, but money supply since 2020 has not been driven by private sector lending, but rather by the Fed’s balance sheet decisions.

This dynamic is obvious when looking at the Fed’s total balance sheet and its measure of money supply, M2. And even if you dislike the composition of M22, it is clear that recent balance sheet movements have had a direct influence on base money (i.e. bank reserves or currency) and broad money (i.e. bank deposits or money market balances).

This new paradigm — money creation by central bank edict — has led to the most dramatic swings of broad money in recent history. First a 27% YoY expansion in M2 during the QE phase of the pandemic — which was necessary to fund the historic fiscal stimulus — and then, a highly unusual contraction in M2 as the Fed sought to put the toothpaste back in the tube.

In the endless inflation debate, it often seems that two sides are talking past each other, and neither appear to be consistent. On the one hand, some folks are so entrenched in blaming the Fed’s money printing for inflation that they ignore the simple fact that the Fed has been shredding money via QT since mid-2022. Others simply wish to excuse fiscal and monetary policy for any blame to begin with and now are taking a belated and disingenuous victory lap for “transitory, supply-side” inflation.

The fact is that rapid inflation occurred during a historic expansion in money supply and that rapid disinflation occurred during a historic contraction in money supply, just as a traditional understanding of monetary policy would dictate. And more importantly these shifts were not driven by interest rates, but rather by the Fed’s balance sheet policy.

I’m begrudgingly rehashing these debates not for a post-hoc adjudication of inflation, but rather to emphasize that balance sheet policy is important — arguably more important than interest rate policy over the past several years.

And beyond the impact on inflation, QE and QT have significant ramifications for the stability of the banking sector.

Reserve Volatility

As a general rule, QE decreases leverage and adds liquidity within the banking system while QT adds leverage and reduces liquidity.

While any single bank has some degree of managerial control over its leverage and liquidity positions, the banking system as a whole is largely at the whim of the Federal Reserve. Banks cannot create or destroy base money, even if they can trade it amongst each other. And as the Fed has shifted back and forth between balance sheet expansion and contraction, banks are forced to contend with these fluctuations.

Pre-2008, the environment was one of scarce but consistent liquidity. Now aggregate bank reserves are far greater, but banks must instead deal with reserve volatility.

This volatility is usually not a problem during QE as banks are de-levering, but can quickly become problematic during QT. In 2019, the first ever round of QT came to an abrupt conclusion as the repo markets froze and required Fed intervention.

The same dynamic can be seen among small banks in the lead up to the Silicon Valley Bank collapse in March of 2023. Again, emergency lending from the Fed (including the newly created Bank Term Funding Program “BTFP”) was required to provide a cash infusion to the banking sector. While cash levels at small banks today remain more robust than March 2023, a significant portion of liquidity comes from BTFP borrowing, which is still temporary in nature.

The Fed has not shown much ability to preemptively address these concerns, despite their own policy being at the center of the matter. At a minimum it suggests that QT is not something to “set and forget”, but rather an inherently delicate undertaking that should be executed with constant attention.

Saving Grace

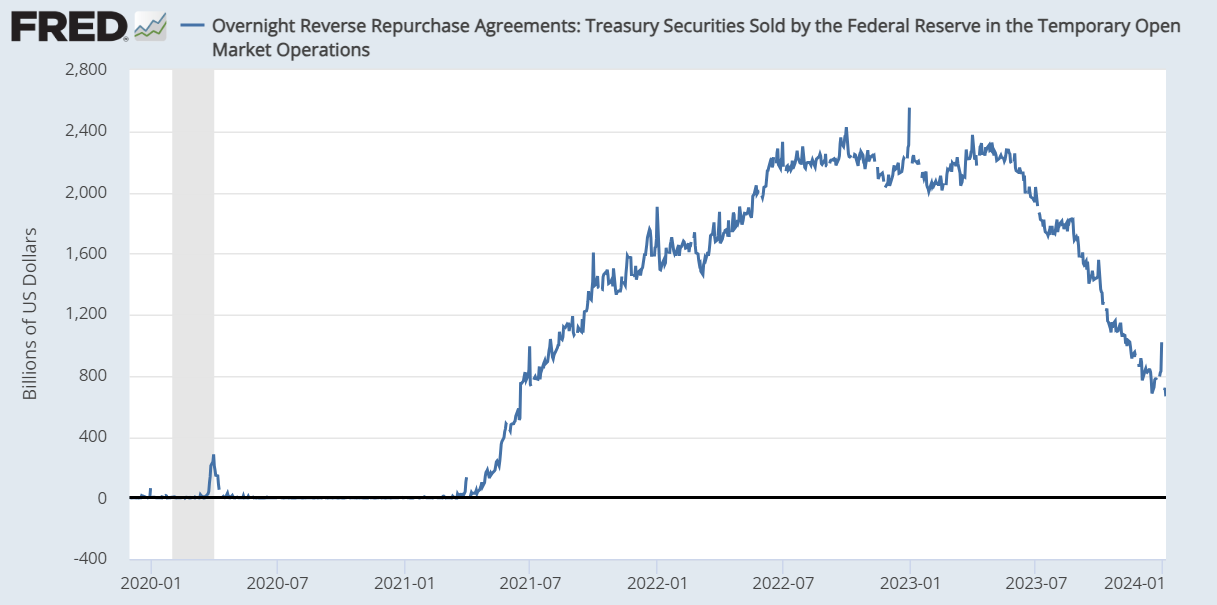

Somewhat ironically, the Fed’s former excess is now its saving grace. An astounding $2.3 trillion of reserves created during the pandemic QE found their way into the Reverse Repo facility (RRP) — effectively an overflow facility meant to enforce the Fed’s short term interest rate target. (For a frame of reference, this total is substantially more cash than was held across the entire banking sector in early 2020).

The Treasury’s massive issuance of T-bills since the debt ceiling was lifted in June 2023 has unlocked this trapped liquidity, allowing QT to continue with relatively little disruptive impact.

The chart below shows the total cash assets across commercial banks (red) and the combined total of bank cash and the RRP (blue). As I’ve highlighted in prior posts, the draining of the RRP since June 2023 has funded the refill of the Treasury General Account (TGA), ongoing QT, and even added to aggregate bank reserves.

But the RRP balance has fallen by over $1,600 billion since this past June, leaving just $664 billion remaining as of this week. Roughly speaking, this should offset roughly six more months of QT at its effective pace of ~$80 billion per month. After which point, ongoing QT must come from bank reserves, adding leverage and reducing liquidity in the banking system yet again.

There is also a growing divergence between the position of small and large U.S. banks. Cash balances at large banks are growing while cash balances at small banks are shrinking. Given that small banks are also more reliant on the temporary BTFP facility, it is likely that stress re-emerges in regional banks if QT continues unabated.

The differing position of individual banks highlights the shortcomings of the concept of the lowest comfortable level of reserves (“LCLOR”). LCLOR somehow assumes that all banks will reach their minimum at the same time. In reality, certain banks are cash flush while others are cash poor, and while there is some amount of rebalancing that can occur among banks, some are destined to run into trouble before a theoretical LCLOR is reached.

Moving Forward

If the Fed is now content with the current pace of inflation, normalizing its balance sheet is at least as significant as cutting interest rates. Balance sheet dynamics have been the primary driver of the swings in money supply and provide a better explanation for the whiplash in inflation than interest rate policy alone. Further, large swings in the balance sheet subject the banking sector to liquidity volatility and rapidly shifting leverage profiles.

In other words, if the goal of 2024 is to “normalize” monetary policy, then the Fed should return to a normal balance sheet — one without massive swings in either direction.

Based on the totality of circumstances, I think it’s possible that the Fed announces a pause of QT around the middle of 2024. Rather than premature, I think such a decision would prove to be a prudent and proactive shift in balance sheet policy — an area where the Fed has too often been reactive.

If QT ends in mid-2024, it would leave the balance sheet at roughly $7 trillion, a 22% reduction from the peak. And while there would still be “excess” reserves in the banking system, it would provide runway for banks to continue to extend private credit and organically expand the money supply for years to come without further influence from the Fed. Banks would be left in a position reminiscent of 2014, not 2019.

Of course, this may not happen. The Fed may choose to let balance sheet runoff continue past the exhaustion of the RRP and attempt to discover the lowest comfortable level of bank reserves by force3. Such a path would allow for further balance sheet shrinkage but is destined to put pressure on the weakest positioned banks, and is likely to prompt an emergency infusion of liquidity at some point down the road. It also runs the risk of unnecessary monetary tightening in a system that appears to be reaching a more healthy equilibrium.

In today’s system, the balance sheet does much of the heavy lifting, and deserves our attention and scrutiny. If the Fed wishes to stick a soft landing, it must normalize both its rate and balance sheet policy.

Thank you for subscribing to The Last Bear Standing. If you like what you’ve read, hit the like button and share it with a friend. Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

TLBS

The number one rule to keep in mind is that when QE/QT involves a non-bank entity, it has a direct impact on broad money supply (M2).

While I think M2 is still a very relevant figure, it is also important to think about the wider range of money-like securities, as discussed in Money on the Spectrum.

If the Fed was to succeed in reaching the LCLOR, the “binding limit” of QT, what happens next? By definition, banks would be reserve constrained and unable to grow total assets without incremental liquidity from the Fed. In other words, taking the balance sheet down to its minimum only ensures the next wave of balance sheet expansion, and therefore is self-defeating.

Superarticle for starting 2024! Thank you Mr. Bear!

Based on the Fed minutes from December’s meeting, it appears Powell and the Fed are already planting those seeds in the minds of investors. The preliminary “talking about talking about” period is upon us.