QE for Dummies

#7: Understanding Quantitative Easing, and why it matters.

Monetary Policy is important. Monetary Policy shapes how our society is constructed; it influences who has a job, who has influence, who is wealthy, who is poor.

Money is Power. The ability to create, distribute and destroy money is a great power.

As the Federal Reserve and central banks around the globe expand their monetary authority and toolkit in exotic and far-reaching ways, it is essential that they be subjected to the highest standards of analysis and scrutiny.

But Monetary Policy - particularly in its modern incarnation- is complicated. The first step to assessing these policies is to understand them: what they do, and what they don’t do. Misunderstanding the mechanics of Quantitative Easing (“QE”) or Quantitative Tightening (“QT”) leads to misdiagnosis. Misdiagnosis leads to bad prescriptions.

I worry that some have misinterpreted these mechanics and their impact on society. I also worry that the policies are either confusing or invisible to the the average person who nonetheless feels the impact and is vaguely aware that something has shifted.

This week’s post will discuss QE, a policy first implemented just fourteen years ago but now essential to interpreting modern finance and economics. Next week, we will discuss QT.

Credible people may disagree with my thoughts below, but I’m compelled to provide my views for others to absorb, disregard or dispute. Hopefully my analysis will be clear and data-centered. I’m obligated to get on my soap box and preach.

Quantitative Easing

Quantitative Easing is a meaningless term, both confusing and boring in nature. Let’s explore the topic with specifics:

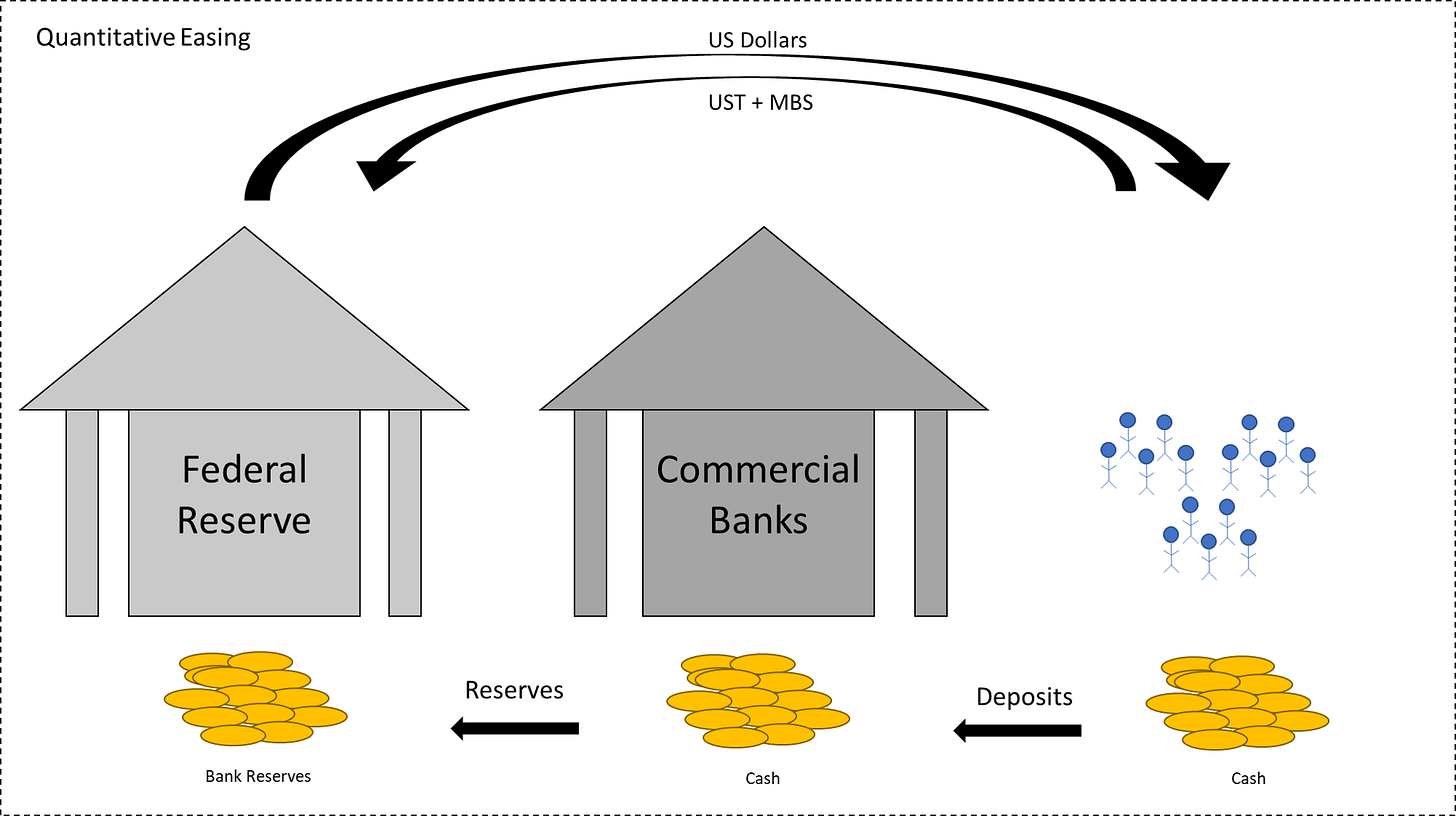

When the Federal Reserve engages in QE, it purchases US Treasuries (“UST”) and Mortgage-Backed Securities (“MBS”) from the public domain. The seller of the security receives US Dollars that were created by the Federal Reserve to fund the purchase. The Fed can purchase as many bonds as it desires; it has an unlimited ability to create Dollars.

There are two direct impacts:

First, the intervention in the UST and MBS market influences interest rates. The Fed’s demand for these securities increases their price and lowers their yield (or interest rate). Since these securities are used as benchmarks for all interest rates, this lowers market-wide interest rates, other things equal.

Second, the number Dollars in existence increases.

Both of these impacts - on interest rates and on money supply - are critical to understanding the current monetary and economic environment, but at times are downplayed due to misunderstanding of the mechanics of QE.

In the following two sections, I’ve summarized two popular theories that I think lead to a skewed understanding of how QE works and its implications.

Gated-Reserves Theory

The Gated-Reserves Theory1 (“GRT”) suggests that while QE may technically create Dollars, it does not create “real” money as we know it. Rather, this line of thinking argues that the Dollars created through QE are stuck in the commercial banking system as “bank reserves”. In order for these reserves to make their way into people’s pockets, commercial banks must loan out this money, creating spendable deposits.

In other words, the central bank provides dry powder to commercial banks via QE, but until that dry power is transformed into real economy money via lending, it is irrelevant. The Fed could do $10 trillion of QE tomorrow with relatively limited real world impact. Commercial banks are the true arbiter of money supply, and the central banks are merely pushing on a string.

There is some merit to this theory:

Historically, commercial bank lending has accounted for a majority of the expansion in money supply. Prior to QE, a central bank’s primary influence on money supply was through interest rate policy to encourage or discourage commercial lending.

If the Fed buys UST and MBS off the balance sheets of commercial banks, total money supply does not increase2.

But critically, Gated-Reserve Theory gets the flow backwards. The Fed is not buying trillions worth of securities off the balance sheets of commercial banks. Rather, a vast majority of UST and MBS is owned by the non-bank investors, not commercial banks. In fact, commercial banks have consistently increased their net total holdings of UST and MBS since QE began, adding over $3 trillion in such holdings since 2010 - the exact opposite of GRT’s implicit insinuation.

Cash in the banking system increases with QE because the Fed is buying securities from investors, and investors deposit their money in commercial banks. In turn, commercial banks store their money with central banks as reserves.

All of these transactions happen simultaneously obscuring the flow - but understanding the direction conceptually is important. The entire point of QE is to allow a central bank to directly intervene in the public markets rather than rely on the power of persuasion through rate policy. The central bank “jumps the gate”.

The increase in cash at commercial banks is not because banks sold assets to the Fed, but rather due to new deposits from investors who sold assets to the Fed3. The cash infusion to commercial banks improves bank liquidity and leverage ratios, increasing the banks’ ability to lend in the process, but that is a second order effect.

Begrudgingly, this point may be accepted by proponents of GRT. They may admit that if4 UST and MBS are sold to the Fed by non-bank investors, then money supply increases, but this still does not constitute real world money because it is held by financial investors. If a large asset manager like PIMCO sells US Treasuries and receives cash, it will just use the cash to purchase another financial asset, rather than spend it in the real economy. This is often referred to as the “portfolio rebalancing effect”.

It may be true that QE Dollars first bounce around financial markets, bidding up financial assets in the process. But there is no wall that separates the financial markets from the real economy. The entire purpose of financial markets is to finance activity in the real economy. Money in financial markets is money in the real economy, even if the transmission process from large scale institutional deposits to individual checking accounts is not immediate.

There are several paths that QE can take to go from its starting place in financial markets to spending on everyday goods and services.

First, when a company raises debt or equity in capital markets, it takes cash from institutional investors (like a PIMCO) and uses it to fund capital expenditures, buy inventory, pay employees or send money to shareholders. As a simple example, think of a company funding salaries through IPO proceeds.

Second, sellers of UST and MBS may simply be liquidating (selling) their investments to buy real world goods or services themselves. This could be a sovereign nation selling UST to buy barrels of oil, or it could be a retail investor selling $TLT (an ETF of long-term US Treasuries) to buy a boat.

A third most direct route is through federal deficit spending. If the Fed provides trillions of liquidity to the UST market to pre-fund US government deficit spending, such as the COVID stimulus packages, the dollars are first brought into the Treasury General Account5 and then sent along to individual checking accounts as stimulus checks or similar measures.

Quantitative Easing creates Dollars, indistinguishable from any others in existence. These new Dollars are injected into the UST and MBS markets, initially bidding up financial asset prices, and over time the trickling down to everyday purchases of goods and services.

Asset-Swap Theory

Another common refrain is the Asset-Swap Theory6 (“AST”). AST correctly notes that a central bank does not give away money with QE, rather it purchases an asset (bonds) with another asset (Dollars) at fair market value. Therefore, the total value of assets held by the public has not changed as a result of QE. Looking only at a single transaction, and ignoring the impact that QE has on the fair market value of bonds, this is true.

AST goes further; the only difference between cash and US Treasuries is duration: cash is just a zero-duration asset. Therefore, QE really only changes the duration of the private market’s balance sheet.

The implication of AST is to downplay the dramatic increase in US dollars in existence as a mere shift in duration of the private sector balance sheet. Such an interpretation leaves one blind to the implications of a dramatic increase in Dollar supply.

It is true that Dollars and short-term Treasuries have similarities, and often times are grouped together. Corporate balance sheets regularly use the term “cash and cash-equivalents” which includes both cash and high quality short-term debt.

But non-cash assets and cash assets are categorically different:

$1,000 is 1,000 Dollars.

$1,000 of UST is a piece of paper that you expect to be able to sell for 1,000 Dollars

We call things “cash equivalent” not because they are cash, but rather because of their ability to quickly and reliably be exchanged for cash. You can’t buy a coffee with a T-bill. You have to sell (or borrow against) the T-bill to get Dollars to buy a coffee. For a corporate CFO, the two may be functionally the same, but to understand monetary policy the distinction is very important.

Because all non-cash assets are priced in Dollar terms, the relative proportion of Dollars to non-cash assets is critical.

All non-cash assets whether financial (equity, debt, crypto) or real (goods, services, real estate) are constantly battling with each other for share of dollar liquidity. How much is a tube of toothpaste or a three-bedroom house worth? They are effectively priced against each other on a relative value basis as they all compete for the same universal asset, Dollars.

If the number of Dollars and the number of non-cash assets remain relatively constant, so too will prices. However a sharp increase in Dollar liquidity without a corresponding increase in the supply of non-cash assets will translate into sharp increases in the prices for those assets.

Since QE reduces the availability of non-cash assets (taking bonds out of the public domain) while increasing Dollar liquidity, the impact is higher prices - both for financial assets and goods and services, other things equal7. Without a massive increase in Dollar liquidity it would be impossible for the prices across asset categories to increase simultaneously.

Conclusion

Since most of this post focused on misconceptions, let us close with the takeaways.

QE increases the supply of US Dollars by purchasing UST and MBS from non-bank financial institutions

Dollars created from QE are not trapped inside the banking system or financial markets

The time lag from institutional deposits to individual checking accounts depends on the path of transmission

Dollars are categorically different than non-cash assets

QE adds Dollars and removes non-cash assets, increasing the nominal price of both financial and non-financial assets, other things equal

Without understanding these mechanics, one would not be able to predict or explain the simultaneous surge in all categories of asset prices; financial, real estate, goods and services. One might also miss the plain reality that the number US Dollars in the public domain has increased eight-fold since QE’s inception in 2008.

By clearly identifying the mechanics of Monetary Policy we can analyze the decisions of policy makers. Nothing here implies right or wrong decisions, but rather it provides a basis of understanding to make such judgements. If you misdiagnosis you will prescribe the wrong medicines. Correct diagnoses lead to the cure.

Next week, we discuss Quantitative Tightening… the conclusions may surprise you.

This is a term I’ve coined here, so it won’t help to Google it. This is meant to be an umbrella for a number of arguments that I’ve encountered with the same basic premise. The purpose here is not to put words in anyone’s mouth or mischaracterize other’s perspectives, but rather to address a school of thought that seems unavoidable when discussing QE in a public forum.

Although even if it is a commercial bank selling the bonds, new Dollars are still created. The monetary base increases, even if broad money supply does not. Perhaps an explanation of different money aggregates would be a good topic for a future post.

I’m front-running any comment that explains in a T-chart how all these accounts balance. I love accounting, I have a degree in accounting, but the difference between an accountant and a businessperson is that an accountant knows how to balance a journal entry, and a businessperson understands what is happening in practice. Of course there is a balanced journal entry for a QE transaction, journal entries must balance by definition, however that tells you little about what is actually happening.

Generally this is presented as an “exception” to the rule rather than acknowledging that all of QE purchases on a net basis have come from non-bank investors.

The Treasury General Account is the federal government’s own bank account. This is where tax receipts and debt issuance proceeds are collected, and in turn funds government spending.

Again, this is a term I’ve coined here.

Throughout the piece, I’ve intentionally avoided using the term inflation because there are many measures of inflation and factors that influence consumer prices in any period beyond strict monetary expansion. The purpose of this piece is to clarify monetary mechanics that allow for inflation.

Love the reading

All models are wrong, some models are useful and some models are dangerous