Money on the Spectrum

#69: Money supply shrinks but capital markets surge.

What is money?

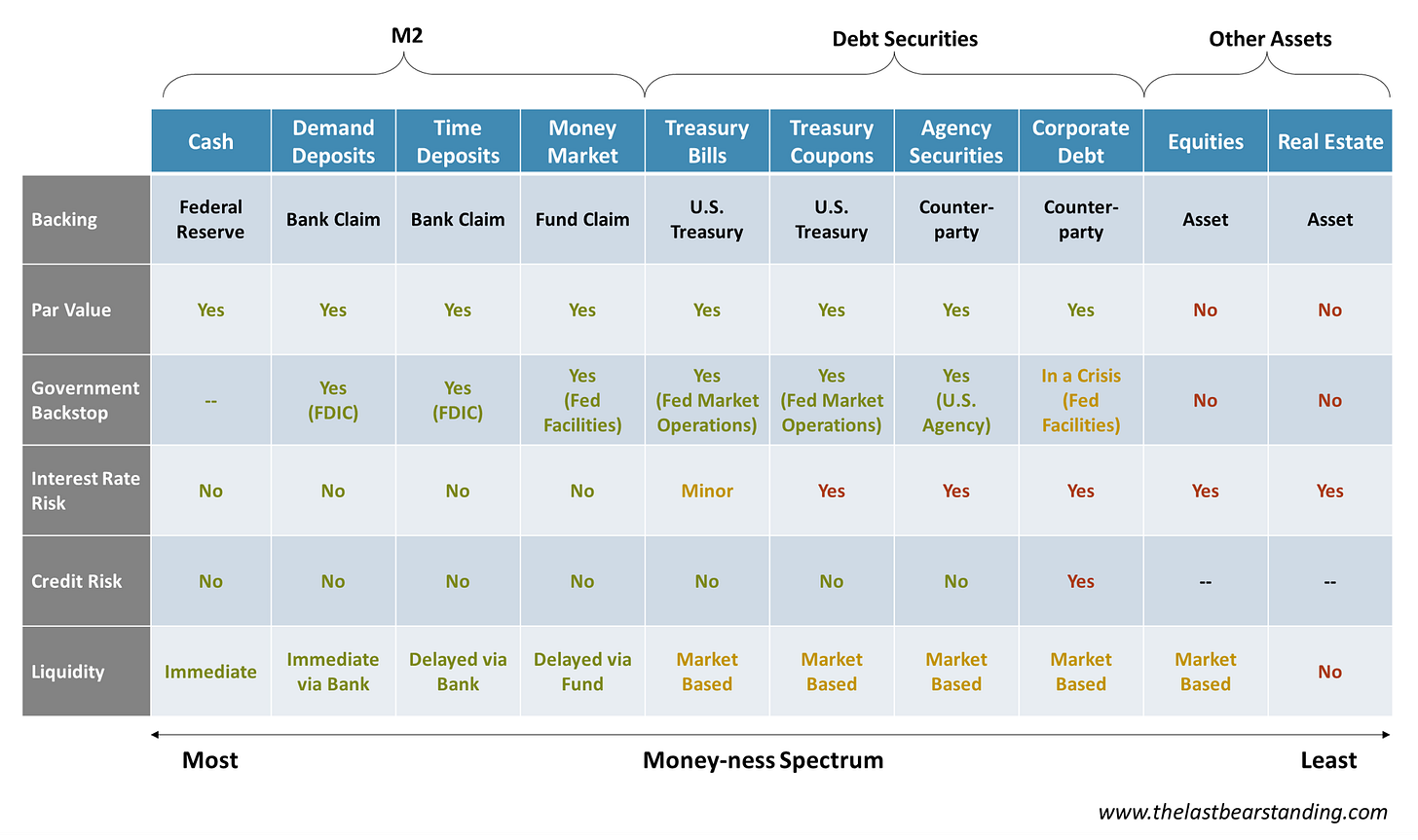

The $20 bill in my wallet is money. The $20 in my checking account is probably money. Twenty shares of a money market fund worth $20 is money-like. How about a Treasury Bill, or a Corporate bond?

Because various assets in the economy and financial system have money-like qualities, it can be surprisingly hard to know exactly how much money exists, how it is created or destroyed, and what it means for the economy. Due to definitional disagreements, money to some degree is determined by the eyes of the beholder. If acorns are money, then money grows on trees.

Traditional measures of money supply (i.e. M2) focus on the banking system - currency and bank deposits1. These are the most spendable forms of money in the economy and therefore deserve plenty of attention. But banking is only one form of credit creation and deposits are only one type of financial asset.

The other major venue of credit creation is capital markets. In the U.S., the majority of debt outstanding doesn’t sit on bank balance sheets but is held directly by investors in the form of securities. According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), debt capital markets provide 75% of debt financing for non-financial corporations (with the remainder coming from bank loans).2

Debt securities are not strictly money because they can’t be used as a form of payment, but many securities can be quickly converted into cash, making them “money-like” in some sense. So long as the market stays liquid and open, these money-like instruments can continue to multiply.

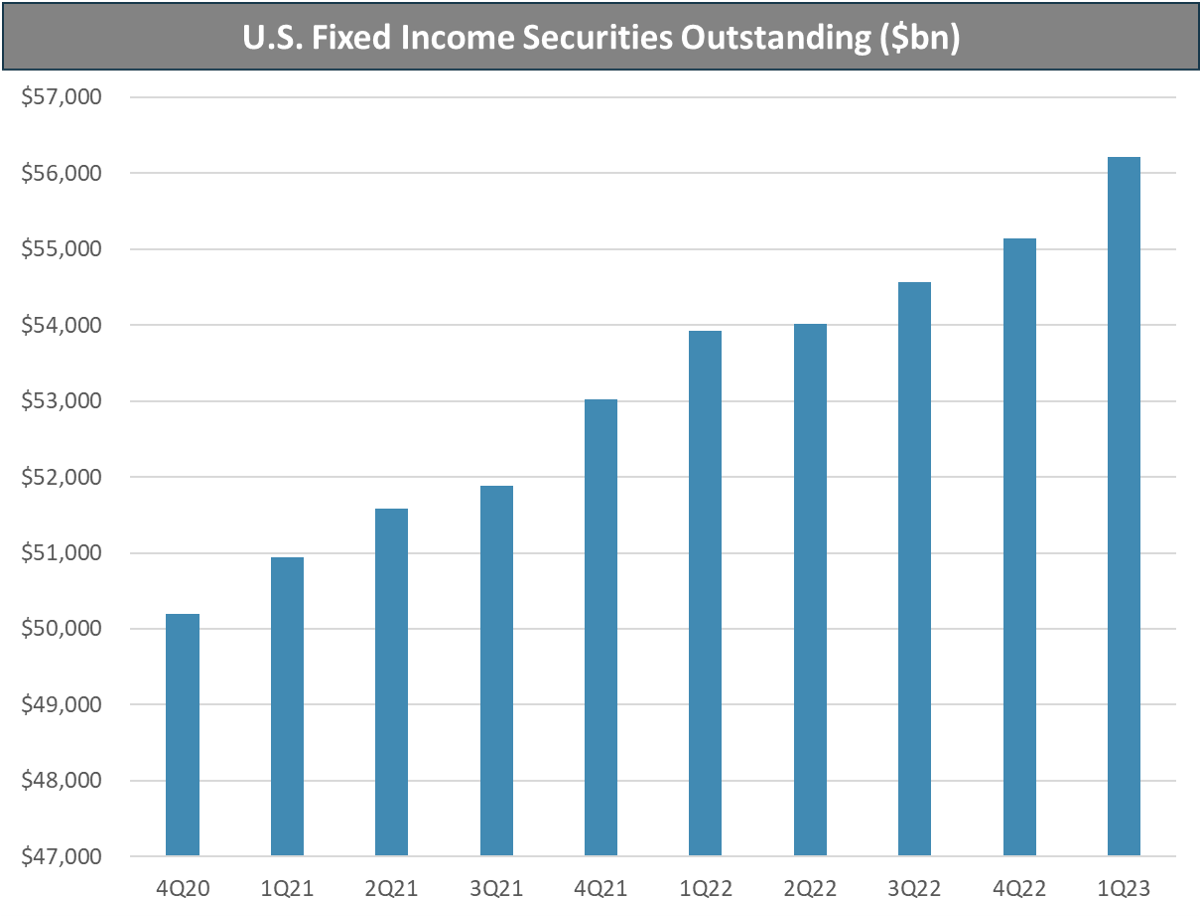

Typically, both money supply and debt securities outstanding are expanding, making the distinction between the two markets less interesting. But today, they are moving in opposite directions. M2 is contracting but the universe of debt securities is growing.

The Spectrum

Bank lending and capital markets function in similar ways. Each transfers money from lenders to borrowers but importantly, the lender maintains access to liquidity. This pooling of capital and provision of liquidity allows the quantity of money to effectively multiply beyond the literal dollars in circulation.

Bank Lending: Depositors lend to borrowers, with the bank serving as an intermediary. A depositor doesn’t care how the bank invests his or her deposits, because the bank maintains enough cash on hand to meet withdrawal requests. If the bank fails, the government steps in. In this process, capital flows to borrowers and depositors maintain access to liquidity.

Capital Markets: In capital markets there is no intermediary. Lenders provide money directly to borrowers in exchange for securities. But lenders rely on an actively traded market if they want their money back prior to maturity. So long as that market functions, capital flows to borrowers and depositors maintain access to liquidity.

Both banks and capital markets enjoy some level of implicit or explicit government backstopping. The Fed provides emergency liquidity to banks and the FDIC insures bank deposits, but the Fed also backstops a wide range of capital markets through specialized facilities and open market operations.

The Fed’s unprecedented market intervention into corporate bonds and ETFs during the pandemic expanded the government’s implicit backstopping of capital markets, beyond U.S. Treasuries and U.S. Agency debt.

Despite these similarities, there are still important differences that affect the “money-ness” of different financial assets. They differ in terms of their backstopping, risks, and liquidity. Money exists on a spectrum.

Rather than draw a perfect box around what constitutes “money”, it’s more important to understand a wide range of claims and securities may have money-like qualities. Moreover, “money-like” credit creation in capital markets should be considered together with traditional M2 measures, particularly given today’s circumstance.

Money Measures

Because the banking system is strictly regulated, we have high quality weekly data on the quantity of deposits and currency outstanding. Bank lending is restricted both by the amount of reserves in the banking sector (a product of central bank policy) as well as banking regulations (a product of legislative policy).

Over the past several years, M2 money supply and bank deposits have been driven largely by the Fed’s asset purchases. Consequently, money supply rose rapidly from 2020 - 2022 during quantitative easing (QE) and has been falling since last summer when quantitative tightening (QT) began3.

Shrinking deposits matter. They represent the most money-like claims and are likely a better indication of the median consumer’s financial circumstance than capital markets which inherently skew towards the investment accounts of the wealthy. The tripling of demand deposits during the pandemic was likely a major driver of excess demand and inflation. Further, as banks feel the squeeze of a shrinking deposit base, bank lending must slow.

But outside the confines of the bank regulatory system, there are no limits on capital market issuance or the number of debt securities outstanding. So long as there are willing lenders and borrowers, the securities outstanding can continue to expand.

Today as M2 contracts, the fixed income market expands. Based on data from SIFMA, the total U.S. fixed income market grew to $56.2 trillion as of 1Q234, more than double the total M2 money supply. The quarterly increase was the second largest of all time, after 4Q21.

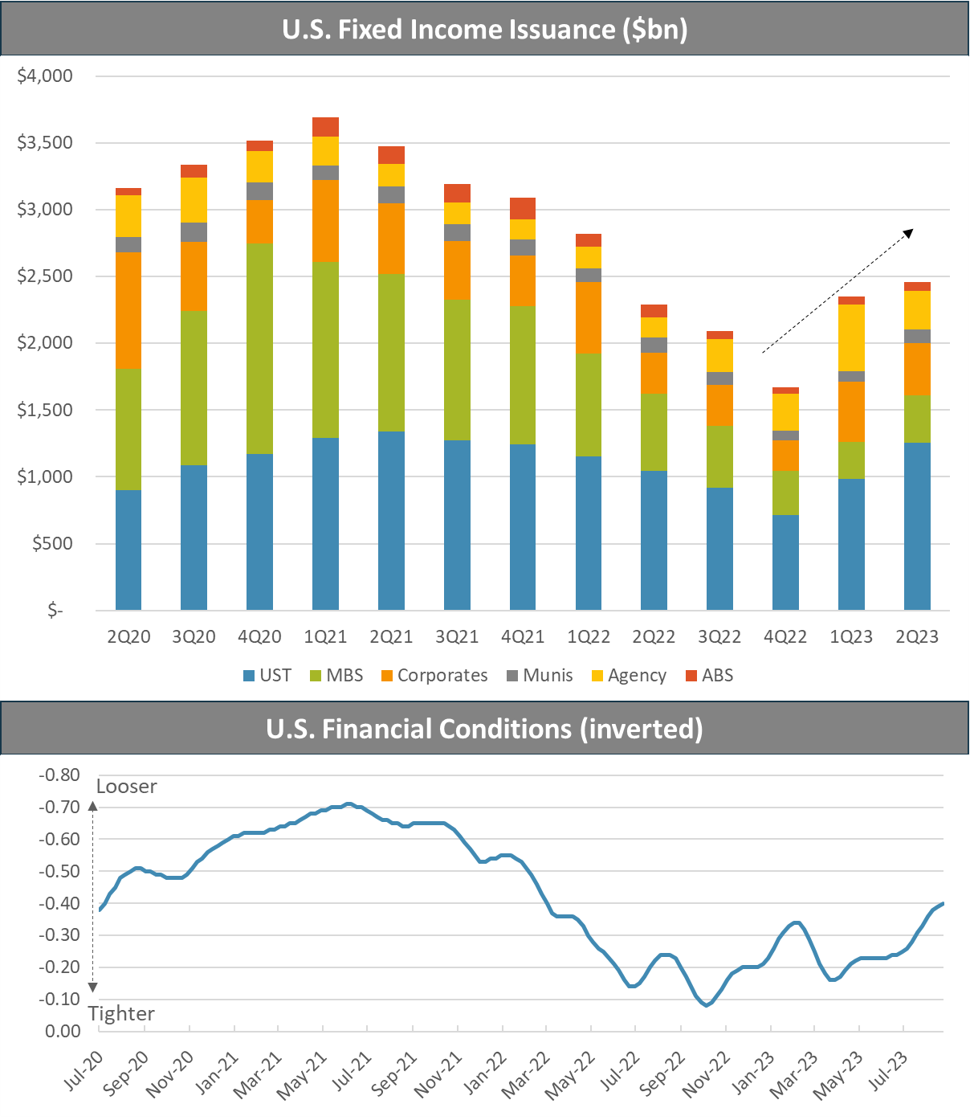

Moreover, while issuance of debt securities initially slowed, as the Fed raised rates and began to shrink its balance sheet, this activity has rebounded substantially in 2023. While still well off pandemic highs, the second quarter of 2023 saw the largest issuance since 1Q22 and a 47% increase over 4Q22 volumes.

The rebound in fixed income issuance has been aided by a broad easing of financial conditions, lower market volatility, resilient economic growth, and a stronger equity market.

In part, this expansion is driven by the U.S. Treasury’s deficits, which are funded primarily through capital markets rather than bank balance sheets. Ironically, the shrinking of bank balance sheets via QT pushes more and more debt creation towards capital markets. While these securities are excluded from M2 and are less money-like than bank deposits, they nevertheless represent claims with some degree of liquidity and government support.

The positive implications for capital flow and economic activity are also important. New credit creation in capital markets provides money for borrowers to spend while lenders retain a liquid financial asset. This credit channel may help explain the surprising resilience of the economy in the face of shrinking money supply (so far).

Finally, as stricter bank regulations are being considered, more and more lending will be pushed away from banks and into capital markets, making it even more important to monitor the size of debt markets along with bank balance sheets when aggregating credit extension and economic health.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, the economic importance of capital markets has only grown, and the money-ness of debt securities has increased.

Post-GFC banking regulations pushed riskier lending into debt markets while bank capital requirements grew more stringent.

Ballooning U.S. fiscal deficits have doubled the size of the U.S. Treasury market held by the public, from $12.5 trillion in 2014 to $24.9 trillion today.

The Federal Reserve’s unprecedented intervention in capital markets during the pandemic expanded the government’s implicit backstopping of a wide range of debt securities.

QT shrinks bank balance sheets and forces capital markets to absorb a greater portion of overall debt.

The recent rebound in capital markets activity in 2023 has helped counterbalance a shrinking money supply and has softened the impact on the real economy. The rebound also demonstrates the significance of loosening financial conditions on overall credit creation, even as QT mechanically reduces bank balance sheets.

Accordingly, capital market activity will be critical in gauging the broad supply of credit and money in the economy going forward.

Happy Labor Day Weekend!

Thank you for reading The Last Bear Standing. To get more content every Friday morning, hit “Subscribe” below. Please let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

As always, thank you for reading.

-TLBS

As well as retail money-market funds. The full definition of M2 can be found at the Fed’s H.6 report.

Generally speaking, deposits are created when banks extend credit or when securities held by non-bank entities are monetized by the Fed in quantitative easing (QE). Deposits can be destroyed through contraction in lending or quantitative tightening (QT).

Note, SIFMA’s US Treasury data only includes coupon treasuries held by the public.

Highlighting what I think is an important distinction - viewing this through the lens of the Perry Mehrling money view / balance sheet framework (all money is someone else’s liability etc) we think about bank lending as money creation insofar as a loan and deposit are simultaneously created “by the stroke of a bookkeeper’s pen.” This balance sheet expansion (and resultant money creation) stands in contrast to the notion of a financial intermediary simply channeling already-existing savings to borrowers.

How do you think about this in capital markets? I.e in order for capital market lending to function as money creation, there needs to be a balance sheet expansion somewhere , right ? E.g. if a high net worth individual funds capital markets issuance with their existing saved income, no money was created.

Obviously if this capital market issuance is funded in repo , and the repo system effectively expands its balance sheet, then that indeed could be seen as money creation.

I guess the main point here is - if bank balance sheets are not expanding, then whose balance sheet is expanding ? Given that we need balance sheet expansion in order for this to qualify as “money creations

Thanks v much

So if money is effectively being forced out of banks and into capital markets - would this explain the great YTD % so far in the stock market is likely to continue? Or is that too much of a reach and simplification?