The Trouble With Charles Schwab

#73: The bank beneath the world's largest brokerage is showing cracks.

I can’t tell you that Charles Schwab is going to go bust — a ticking time bomb destined to blow — because it’s not necessarily true.

But objectively, the company’s financial position has substantially weakened. Its bank deposits have fallen by $202 billion or 44% over the past five quarters. Deposit outflows have strained the company’s liquidity, forcing the firm to draw down its cash balances and turn to short-term borrowing to plug the gap. At the same time, the firm has experienced substantial unrealized losses on its large security portfolio, reducing its equity capital. As a result the company’s Tangible Common Equity capital sits at just 1.8% of total assets as of June 30, 2023. By fair-market-value, the company likely has negative tangible equity value today, despite a market capitalization of $99 billion.

The future of Charles Schwab hinges on what happens next — customers’ decisions, monetary policy, regulatory action, and how the firm navigates these challenges. Today, we take a closer look.

Background

The Charles Schwab Corporation (NYSE: SCHW) is a financial conglomerate, most well known as a securities broker, investment advisor, and wealth management firm. Over the years, its assets have grown organically and through acquisition, reaching over $8.0 trillion of client assets as of June 30, 2023, making it the largest brokerage in the world.

The Charles Schwab Corporation (CSC) is actually a holding company that operates through subsidiaries, including one primary bank and several broker-dealers1.

A majority of the firm’s assets and liabilities reside at its banking subsidiary, Charles Schwab Bank (CSB), which holds the cash balances of its brokerage accounts. Both CSC and CSB are subject to banking regulations, designated as a Financial Holding Company and a Texas-chartered savings bank, respectively.

With $515 billion of consolidated assets, the company would rank as the 9th largest bank in the country by assets - roughly 2.5x larger than Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic. Meanwhile, its total client assets rank puts it among the largest asset managers. Because its size and importance, its financial health is consequential.

Deposits & Liquidity

The primary source of funding for Charles Schwab Bank is cash deposits from the firm’s brokerage accounts. When customers transfer cash to a Schwab account, it is deposited and held within CSB until it is used to purchase investments.

While the decline in system-wide banking deposits is primarily a function of quantitative tightening rather than “yield chasing” or “deposit flight”, Charles Schwab is the exception.

Unlike most normal banks, where individuals and businesses hold deposits for everyday transactions and spending, Charles Schwab Bank’s deposits are specifically earmarked for investment. Deposits at the bank are inherently seeking the highest return and reside on a platform that facilitates exactly those types of transactions.

Therefore deposits at Schwab Bank are uniquely sensitive to increases in interest rates - as the company duly notes throughout its SEC disclosures:

Our clients’ allocation of cash held on our balance sheet as bank deposits or payables to brokerage clients is sensitive to interest rate levels, with clients typically increasing their utilization of investment cash solutions such as purchased money market funds and certain fixed income products when those yields are higher than those of cash sweep features.

Indeed, as rates have risen, customers have invested in these higher yielding products, moving substantial sums out of the bank. Excluding brokered CDs, the company has lost $202 billion or 44% of its total deposits from $465 billion in 1Q22 — the start of Fed’s rate hiking cycle — to just $263 billion as of 2Q23, an average loss of $40 billion per quarter.

Today, Charles Schwab’s organic deposits are at the lowest levels since December 2019, before COVID unleashed the monetary bazooka. While deposits have shrank across the banking sector over the past year, CSB’s declines are truly unique. Total deposits at all commercial banks have fallen less than 4% since 1Q23, compared to 44% at Schwab.

To plug this unusually large cash outflow, the company has drawn down its cash balance, reduced its securities portfolio, increased short-term borrowings, and brokered high-cost Certificates of Deposit, as shown below.

Yet, even as the dramatic decline in deposits has stretched the company’s liquidity position, it maintains access to substantially more cash if needed.

Per its 2Q23 10Q, Schwab details $95 billion of available liquidity through existing pledged collateral, and a total available liquidity of $315 billion when including unpledged collateral and cash on hand. A large majority of the borrowing capacity comes from the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB) and the Federal Reserve via the Bank Term Funding Program and Discount Window, secured by the company’s portfolio of loans and securities.

Given these resources, the company can technically cover ongoing deposit outflows. Though with market interest rates over 5% compared to its current asset yield of 3.36%, any incremental borrowing or brokered deposits would be dilutive to net interest margins today and capital balances over a longer term. Further, maxing its FHLB capacity and usage of the Fed’s facilities would likely draw increasing concern around the firm’s financial health.

Nevertheless, the company is not in imminent danger of a liquidity crisis at the status quo trajectory. And there are decent reasons to expect that deposit outflows will ease.

For one, the Fed’s hiking cycle has slowed, with only 25bps of incremental hikes since the end last quarter2. Secondly, there is probably some minimum level of cash that investors will hold as a result of ongoing trading activity, or simple ignorance to the preferential rates elsewhere. The company noted in its 2Q23 earnings call that deposit outflows slowed substantially throughout the quarter.

In isolation, this drawdown in deposits and liquidity is damaging but not existential. But the drawdown is not happening in isolation.

Equity (in the Eye of the Beholder)

While rising interest rates have driven deposit outflows, pressuring the company’s funding (or liabilities), it has also impaired the value of the company’s assets.

In particular, the company’s $292 billion security portfolio, primarily consisting of U.S. Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities, has a weighted average interest rate of just 1.9% - well below today’s market rates.

As a result, the company has unrealized losses totaling $27 billion across its available-for-sale (AFS) and held-to-maturity (HTM) securities holdings. The fair value of its small loan book has also declined by $3 billion, bringing the total unrealized losses across its assets to $30 billion. Roughly $21 billion of these losses are included in the firm’s reported Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI), while the remaining $9 billion are not3.

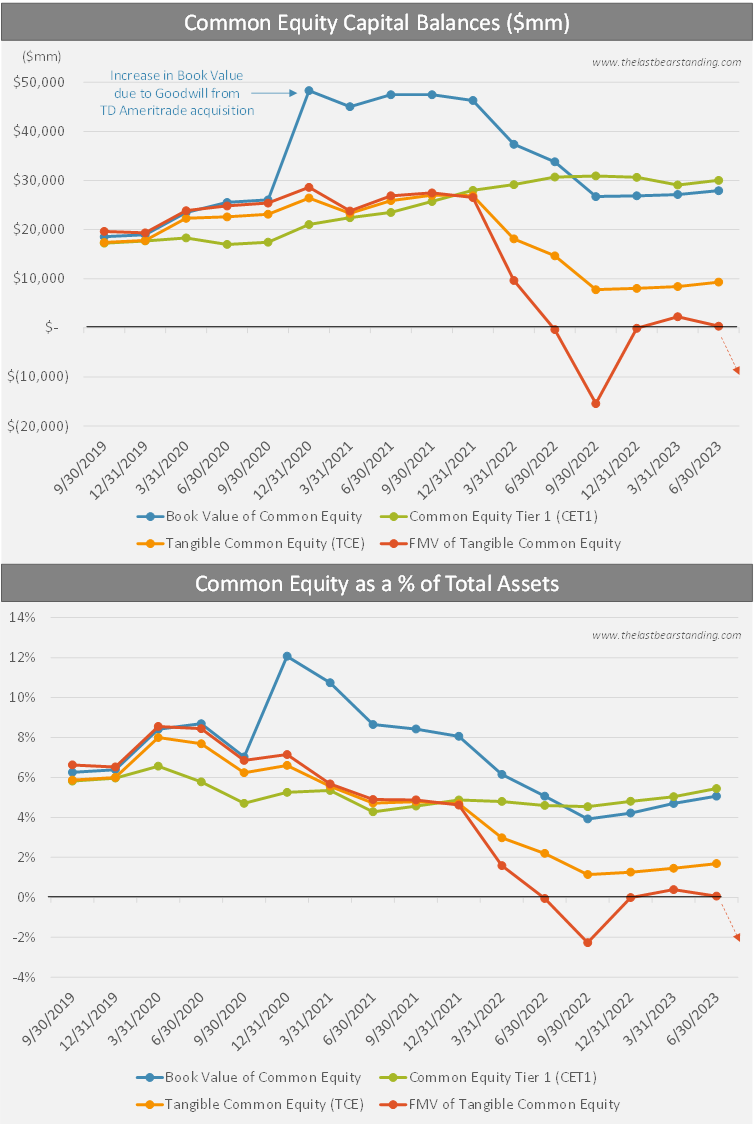

These unrealized losses have significantly impaired the company’s equity capital position - the difference between the value of its assets and liabilities (depending on who’s asking).

There are many different ways to measure equity capital, and in this circumstance, the methodology you assume leads to vastly different conclusions about Schwab’s health. Below we chart the progression of four measures of equity capital (a full reconciliation is included in the Appendix).

Book Value of Common Equity (GAAP)

Common Equity Tier 1 (“CET1”) (used for most regulatory purposes)

Tangible Common Equity (“TCE”)

Fair-Market-Value of Tangible Common Equity

Using the more practical Tangible Common Equity or FMV of Tangible Common Equity, we see the notable decline in the company’s equity balance since early 2022. Even the book value of equity, which includes intangible assets like goodwill, has been shrinking materially since rate hikes began.

Despite this, Schwab’s CET1 - the primary measure used for regulatory purposes - stands at $30 billion - and has remained relatively constant over the past two years even as all other equity measures have deteriorated substantially. Why?

Given Schwab’s size, it is able to qualify as a “Category III” bank under current regulations. Category III banks can exclude AOCI from their capital calculations.

Schwab’s CET1 regulatory capital excludes all $30 billion of its unrealized losses.

Does this treatment seem prudent given that unrealized losses had led to two of the largest bank failures in recent memory earlier this year? It doesn’t. And new regulations are set to change this treatment.

According to the Fed’s recently announced plan, this AOCI exclusion will be phased out over a three year period beginning in 3Q 2025.

Under current treatment, both the Charles Schwab and the Schwab Bank subsidiary, pass the Tier 1 Leverage regulatory test by excluding $20 billion in AOCI losses. But without this AOCI exclusion, neither CSC or CSB would meet minimum capital requirements today - a point that is made explicitly in the company’s filings:

As of June 30, 2023, our adjusted Tier 1 Leverage Ratio, which reflects the inclusion of AOCI in the ratio, was 3.7% for CSC consolidated and [3.98%] for CSB [compared to a minimum requirement of 4.0%]… The Company is continuing to accrete and retain capital while it continues to evaluate the impacts of the proposal.

If this regulatory change comes to pass as intended, it will be a headwind to Schwab’s earnings and balance-sheet flexibility, as it is forced to de-lever.

But even this AOCI inclusion will still omit unrealized losses on its loan book and HTM portfolio, which are substantial. Using fair-market-value across the firm’s entire asset book as of June 30, 2023 - approximately $30 billion - the company had effectively zero tangible equity value. And rates have risen substantially since then, to the highest levels since 3Q22.

When the firm closes its third quarter books using today’s market values, it will record a material drop in fair values. Using mortgage-backed security ETFs as a rough proxy for the impact of the interest rate change over the past three months, the total value of Schwab’s securities will decline roughly 4.5% from current fair values, or an incremental ~$13 billion of losses.

Because most of these losses will occur within the HTM portfolio (rather than AFS), there likely won’t be a substantial decrease in the company’s calculated book value of common equity, CET1, or even tangible common equity. But nevertheless, on a fair-market-value basis the company will report negative tangible equity capital.

Does this matter?

The firm has liquidity available to conduct its operations. Its reported regulatory capital ratios will continue to look fine. Its reported Tangible Common Equity will remain thin, but positive.

A negative FMV of equity only matters if people decide that it matters.