The Matador

The 2025 Bear Market

In the ancient spectacle of the bullfight (or corrida de toros), the Matador must understand the bull's nature, anticipate its movements, and recognize the precise moment when its confidence becomes its vulnerability. The corrida is carefully planned and executed, layered into a series of phases that must each be completed skillfully before the killing blow (the estocada).

The Matador must remain calm, knowing that behind the frenzy is the inevitable exhaustion. And the moment that exhaustion appears, perhaps even before it is known to the bull (who has been in a frenzied attack for hours), the death blow is delivered.

In markets, like bullfights, the ferocity continues until it absolutely can no longer. If there is a singular task that every bull market in history has accomplished with ruthless efficiency, it is the silencing of contrarian voices by the end of its run. Those with the audacity to have warned of risks before the point of absolute exhaustion end up derided and ignored.

This effect persists well after prices have begun to crack, and when combined with the lessons of recent successful bouts of dip buying, create the “complacency” phase of perhaps one of the most acknowledged and ignored charts in markets.

While the length of this piece is…manifesto-y, it’s a necessary exercise in examining the market holistically. That’s because I am more convinced than ever that we have entered the complacency phase of the cycle.

While recent events have taken some of the air out of the most egregiously crowded trades in the market, we have so much further to go. Exceedingly few are truly positioned for the bear market and the bulls haven’t given up without a fight. Investors are frozen, even as they realize that things are, in fact, getting worse.

However, there are still a few that see this for what it is. One of those is my friend and legendary strategist Marko Kolanovic, unique among Wall Street’s outspoken voices for not capitulating on his conviction that the market has climbed to unsustainable heights and is complacent, if not ignorant, to the significant downside risk.

In many ways, he is truly one of the Last Bears Standing. He’s been kind enough to author the foreword to Matador: The Bull Killer

Foreword

By: Marko Kolanovic

When my friends at The Last Bear Standing asked me to write my thoughts about markets, I agreed. I have been intensely thinking about recent market developments and the enormous levels of uncertainty across the world—perhaps last seen during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the 2020 pandemic.

Let me start by saying that global macro and geopolitical developments are so profound and complex that one should assess developments day by day and remain flexible to adjust their outlook based on new developments.

Before formulating a view, one needs to first understand where we are currently in the historical context and, more importantly, how markets arrived at their present state. I will start with the 2020 COVID crisis—a great recession that never materialized due to a massive wave of fiscal and monetary easing across the world. As such, the 2020 recession never performed its role of purging unviable businesses and market excesses, and hence it never set the stage for healthy and sustainable growth. If anything, we saw the emergence of inherently worthless assets and shaky businesses with sky-high valuations. Economies grew increasingly dependent on government projects and handouts. It should not be surprising that the combination of COVID disruptions and these monetary and fiscal excesses resulted in inflation not seen since the 1970s.

When the Federal Reserve (being late) began hiking rates in 2022, air came out of broad markets and various speculative assets. Inflation breakevens dropped quickly by early 2023, but the Fed continued hiking to 5.5%. The yield curve inverted—a historical signal of recession. I did not believe that markets would thrive in 2024 with these high rates, even though recessions typically start with a significant lag (1–2 years after yield curve inversion). However, in 2024, everybody forgot about the inversion, rising defaults and recession risks, and it became extremely rare and unpopular to have a cautious market view. Despite near-unanimous optimism, low-end consumers still faced pressure from high credit card and other debts, small businesses struggled with financing costs, and real estate markets remained paralyzed. These concerns were set aside as the economy thrived on promises of AI, the stock market’s wealth effect, record government spending, and interest rate cuts that began just before key elections (here). Markets ended 2024 with P/E multiple near the highest level since the dot-com bubble burst, with narrow leadership—concentration levels not seen in over 50 years. However, there were many signs that a major rebalancing in markets is about to happen which I discussed here, and here.

It didn’t take very long for a correction to begin. The bubble in momentum stocks (both large and small) started unraveling in January 2025 (here). If a stock has a multiple of ~400, a 40% drop should not surprise anyone (here). What followed, however, was far more devastating for markets and the real economy: the start of an unwinnable trade war between the U.S. and much of the world (here, here). Students of markets should recall the first trade war in 2018—not only President Trump’s tactics and response functions, and his relationship with Chairman Powell (here), but also take into account the differences between his first and second presidential terms. I warned that markets would experience a larger drawdown, with the so-called put option strike lower than most anticipated (here, here). Since the trade war began, damage has grown daily, and most economists now estimate a ~50% or higher probability of an imminent recession. In early April 2025, markets crashed, and the VIX reached levels seen during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and COVID-19 pandemic.

The probability of a recession is indeed very high, and we may already be in one. Notably, the yield curve inversion that started in 2022 typically indicates a recession when the curve finally un-inverts. Well, three years after the first rate hikes, we saw that signal in 2025. Declining asset prices (both stocks and bonds) have eroded the wealth effect, negatively impacting economic activity. The new administration intends to cut, rather than increase, spending. Low-end consumers continue to struggle, and with the prospect of layoffs, their situation is likely to worsen. The trade war is expected to slow the global economy, and the Fed is not yet signaling relief just yet (here). In addition there is a risk of inflated private assets and crypto.

Where does this leave us after the recent bounce and partial market retracement? The S&P 500’s forward multiple is 20x, and earnings are not properly reflecting recession risks. With a multiple of 20x, how much upside remains? In many recent crises—such as the 2002 double bottom, the 2011 European debt crisis, the 2015 emerging markets crisis, the 2018 trade war, and the 2022 rate hikes—the S&P 500’s multiple dropped to ~15, suggesting a ~20% decline from current levels. I have not yet heard a compelling argument why the multiple would not fall to ~15x and remain there for more than a few days during this crisis. Even assuming a quick earnings recovery to $300, a multiple of ~15x would place the S&P 500 below 5,000. Worse scenarios are plausible: if earnings decline (as in a recession) and the multiple drops to ~15x, the S&P 500 could fall to the high 3,000s or low 4,000s. Even more severe outcomes, though less likely, are also possible—during the GFC, earnings plummeted, and the multiple fell to ~12, and stayed there for a few years.

Downside risk for markets remains substantial, with limited upside after the recent rally. Current prices assume an optimistic resolution to the significant economic, political, and geopolitical challenges the world faces. Trade with caution and evaluate new developments as they arise.

Marko Kolanovic, PhD

Traje de Luces: The Setup

There is a moment when the writing is on the wall for anyone that cares to look, but few do. I would describe this well-established dynamic, but there is no way I’d do it better than Colm O’Shea in his Hedge Fund Market Wizards interview:

Anyone that has been paying close enough attention can see the echoes of the last market top and reversal. Today, we face some similar concerns to the ones that unwound the 2021 peak – a compression in multiples from an overheated equity market, cost and inflationary pressures, and trade concerns.

But in 2022, the US economy was still in a strong state of rebound with a massive labor shortage and rapid jobs growth. Inflation was largely driven by excessive demand and the negative drag of monetary policy was balanced by a growing fiscal impulse.

Today, economic growth is slowing after reaching unsustainable levels. Trade is coming to a halt and fiscal outlays are being slashed. The easy narrative of inflation reversion and Fed panic has given way to a multitude of threats. The days for this bull market — built on unsustainable capital allocation, misplaced trust in institutions, and a speculative fervor — are over.

Here is the opinion of this Bear. The market’s current decline is not a correction, a bump in the road, or a dip to be bought.

We have entered a protracted bear market that will result in sub-par equity returns from current levels. If investors push this bear market rally higher, I will be happily selling to them the whole way. This unwind has been in the making for nearly four years, and now it is time for the conclusion..

The Three Pillars of the New Bear Market

The market today faces a unique and dangerous confluence of risks spanning three critical categories. They are:

Macroeconomic risk: Growth is sputtering: Real GDP is decelerating, credit stress is growing, consumer sentiment hovers near a 70-year low, and factory surveys flash bright red. These cracks, formed before the latest policy shocks, have been split wide open.

Policy risk: Washington has flipped the script on globalization: Tariffs have halted Chinese goods and alienated allies, while shocking ports, supply chains and prices. The fiscal impulse has reversed.

Market risk: The foundation is brittle: Valuations assume earnings growth that no sober model supports. Leverage in ETFs and options will serve to shatter the glass house they helped construct. Complacency sets the stage for a slide worse than 2022’s shake-out.

Every bear market tells a story. The narrative often crystallizes around a central theme, a dominant fear that grips markets and drives asset prices lower. We saw it in 2022, as the specter of runaway inflation and an aggressive Federal Reserve ended the post-COVID euphoria. We saw it in 2020, when a novel virus (extremely briefly) brought the global economy to a standstill. Go back further: the 2018 taper tantrum, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis born from subprime excess, the 2001 bursting of the dot-com bubble. Each downturn had its defining characteristic, its unique signature of risk.

Today, as markets navigate treacherous crosscurrents, the question arises: what is the theme of this potential bear market?

It is hard to put a neat box around the innumerable and cross correlated factors of market pricing. But, across the landscape, several undercurrents keep appearing – the three pillars of the new bear market.

First, is the Capital Cycle

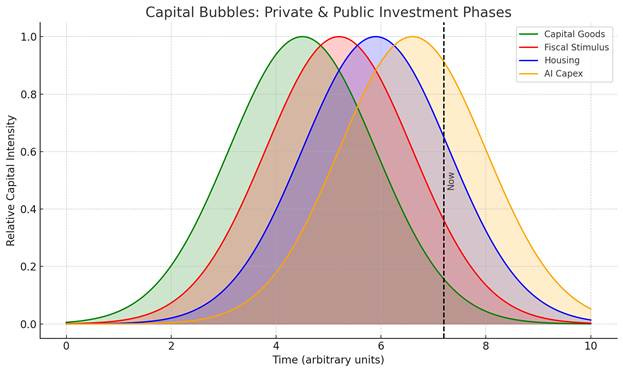

The market has benefited from both a public and private capital cycle, driven by new technology and stimulative policy. The effects on estimates and earnings alike has been impossible to miss. But the cycle is turning.

Second, is the Trade War.

Without exaggeration, we are witnessing the most dramatic rejection of the free-trade ethos that has defined the post-Cold War era – an ethos that has greatly benefitted corporate valuations and profits.

Finally, there is the Market Mirage.

Driven by crowded trades and the proliferation of leverage, many stock have completely disconnected from fundamentals. What’s more, an overwhelming sense of investor complacency has emerged out of a virtuous cycle of reassurance from the market’s consistent rebounds. Signal after signal, sometimes dire, are ignored.

Calling a bear market is one thing, the real question is how to trade it?

This is my first comprehensive analysis of asymmetric opportunities as we enter what is sure to be one of the most hated bear markets in history. Complacency may last for longer than is comfortable on the short side, it always has. Take, for example, 2008…

The writing was on the wall as early as 2007. Bear Stearns collapsed in March 2008. Still, by mid-May, SPX was a meager 9% off of its highs.

So, as we prepare for the inevitable conclusion to this saga, here’s my cross-sector, high-level takes on the micro aspect of a very macro slowdown. I explore how each of these risks is likely to manifest in single names and discuss setups I feel will serve well as the market weakens.

I. Macro Risk: Tercio de Varas

Even before tariffs throttled trade and policy chaos cracked the confidence of CEOs, the underlying economy was flashing warning signs. Consumers — especially low and middle-income consumers — have been struggling for years though widely ignored. The employment market has been deteriorating since 2022.

Consumers polled by the University of Michigan expecting worse business conditions in a year is at its highest level since the survey began, which began rising in Q1 2025:

Outside of the lucky few, businesses aren’t faring much better. Borrowing costs have remained elevated for nearly the years, dashing the hopes for a refi for those struggling with debt service coverage, and small businesses are reporting the worst outlook on the economy that they have in years. PMIs have been in contraction for five months, trucking volumes are already down ~20% YoY and the wave of negative earnings guidance revisions is surging higher. Long before the recent collapse in new orders, manufacturing optimism had peaked most surveys:

And while we are nowhere near the default rates that were present even before the GFC, it’s evident that any sort of buoyancy to the consumer’s position provided by COVID-era stimulus has been completely exhausted, as evidenced by high levels of serious delinquencies.

Sometimes, it’s as simple as listening to the companies. Downward EPS guidance revisions have increased to the highest level since the 2022 downturn.

Earnings calls have taken a dour turn. Just over the past week:

“Saving money because of concerns around the economy was the overwhelming reason consumers were reducing the frequency of restaurant visits.” — Chipotle CEO Scott Boatwright

“Relative to where we were three months ago, we probably aren’t feeling as good about the consumer now” — Pepsi CFO Jamie Caulfield

“I don’t care if you call it a recession or not, in this industry, that’s a recession” — Southwest Airlines CEO Robert Jordan

Back in February, Equifax flagged a slowdown in hiring that had not yet translated to a meaningful increase in unemployment claims — but it’s hard to imagine that doesn’t come to fruition after what’s occurred since. The labor market has been cyclically tight, but not secularly in the way some would have you think.

Put simply: the real economy can’t hold up given the massive headwinds it faces. The market may have rebounded, but the consumer is strained and the corporate sector is cautious. The sugar highs of fiscal spending are wearing off. And with cost pressure suddenly rising, the Fed is boxed in and government policy backstops will see none of the bipartisan support nor the speed of the COVID bills (and to some degree the IRA) that saved us from recession in 2022.

The Capital Cycle

Capital investment is at the heart of economic growth but also highly cyclical. This duality explains how massive capital buildouts, from railroads in the 1850s to internet infrastructure in the last 1999s, often coincide with market booms and busts. The underlying technology is often a long-term winner, but the pattern of optimism leading to overhype and overcapacity is repeated again and again.

The nature of accounting also adds to these swings. In the early phases, there is a widespread overstatement of earnings as the spender’s costs are capitalized while the providers immediately recognize these sums in earnings. As the expense shows up in lagging depreciation earnings it depressed earnings for future periods.

This cycle we’ve just lived through was driven by a surge in capital goods, fiscal spending on infrastructure, new residential construction, and a massive buildout AI. The timeline looks something like this.

We’ve already seen the boom…

AI: Shifting Narratives

After leading the market for much of 2023 and 2024, sentiment for the AI capex trade has clearly already peaked. Early signs of wavering were amplified by the DeepSeek scare — the first true moment of disbelief.

The AI buildout, a key driver of both economic and market activity over the past two years, is no longer a clean macro story. Capex remains high, but efficiency demands are rising. As LLM commodification concerns lead to more prudent and exacting capital plans, many of the “AI winners” are being reset. The next leg requires proof of ROI, not just ambition.

Hyperscalers, which hold the handle of the bullwhip, are increasingly cautious on excessive capex, after already committing to some of the massive spending ever undertaken in the tech industry. Now, architectural improvement and commodification of the LLM foundational models — not to mention the sheer scale of current spending — threatens the ROI on investment while a wave of depreciation expense is only beginning to drag on earnings.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that AI capex is going to collapse. Rather, I’m arguing that it’s impossible to maintain the rate of change that has occurred over the past two years. For picks and shovels, the rate of change is critical, as they require increasing investment for ongoing growth.

Moreso, market perception and valuation is likely to overshoot fundamentals on both the upside and downside. If there is a moderation, pause or decline in hyperscaler capex, the bullwhip will sting through a long value chain of suppliers and beneficiaries, from chips, to hardware, to integrators, and datacenter hosts.

All of these companies, and their suppliers, owners, and employees, have a significant exposure to the direction of spending.

Betting against the capex cycle is not a bet against AI. It is a bet based on the psychology of the hype cycle, a moderation of spending growth rates, and an evolution of more efficient AI development across both training and inference combined with the ongoing rapid deployment of incremental GPU capacity.

Here are the names most at risk.

First up, after collaborating on the Haves vs. Have Nots, I’ve asked CitriniResearch to weigh in on the risks to the King Kong of the AI trade: Nvidia.

NVIDIA Corporation (NVDA)

The semiconductor complex, led by Nvidia, has driven markets for much of the 2020s, but cracks are showing. Nvidia still walks on water at 20x next-year sales and a 75% gross margin, yet markets rarely let one firm own a gold rush forever. Five cracks already spider across the surface: customers rolling their own chips, insurgents routing around Mellanox, software abstractions flattening CUDA, efficiency breakthroughs bending the compute curve, and a product road map that keeps skipping beats. When perfection is priced in, even a hairline fracture can wobble the story.

First: the hardware. After years of writing blank checks to Nvidia, hyperscalers now parade TPUs, Trainiums, and next-gen ASICs that hit “good-enough” throughput at cost. Cerebras welds an entire 300mm wafer into one die and Groq’s deterministic TPUs run 1,400 tokens per second. Both dodge the bandwidth chokepoint that props up Nvidia’s ASP. If a data-center manager can clear the same inference load with fewer boxes, the H-series premium looks fragile.

Second: the efficiency gains. While the parade of Jevon’s Paradox explainers has subsided, it still seems as though there is a disconnect between market understanding and the reality of exponential efficiency improvements. My first interaction with The Last Bear Standing was after he called the top in the AI Power Trade, and those insights (that power efficiency will likely result in power demand not expanding due to AI at the pace the market expects) apply across the technology - not just in the power theme.

Third: the cycle. A refrain I’ve found myself repeating all too often over the past 5 years or so: Just because AI or <insert exciting new technology> is a real thing does not mean semiconductors aren’t cyclical anymore. Nvidia just ate a 5.5 billion-dollar writedown on Hopper-derived H20 parts that never found a home. Blackwell, a stop-gap tuned for jumbo context windows, arrives as customers digest excess gear. Management is already teasing “Rubin,” a lower-precision workhorse aimed at robotics. Three overlapping architectures, swelling inventories, and a softening order book rhyme with the margin punch-out that clipped the stock in 2022. It’s starting to feel like we’ve seen this movie before.

Put this all together and the asymmetry tilts bearish, although NVDA is certainly an excellent operator and a company I’d want to own, the fact is I can’t underwrite these risks currently with the potential for such minimal near-term reward. A modest dip in compute demand or a modest nick to pricing cascades straight through a high-operating-leverage model. Cracks in the armor of NVDA’s CUDA moat or a significant series of breakthroughs on ASICs or TPUs from Amazon or Google. More open-sourced efficiency improvements a la DeepSeek.

Now, NVDA is not just training, and inference demand accelerating can be a big tailwind (although AMD may be better positioned and have more favorable base effects for that occurrence). Rubin could ship cleanly while buybacks plug the valuation gap.

Still, when every pixel of the canvas is priced for brilliance, “good” can trade like “bad” and “not perfect” can still pay.

Oracle Corporation (ORCL)

As early mover Microsoft takes a step back, Oracle is beginning to fill its shoes taking on much of pre-training capex through its Stargate partnership with OpenAI and Softbank. But unlike Microsoft, whose massive growth in profitability over the past several years has provided plenty of organic funding for capex, Oracle is going “all-in”.

Even as Oracle’s current capex spending is smaller than the other hyperscalers, it is much larger relative to its cash flow generation. In the most recent quarter, its $5.8 billion capex spend was equal to its entire cash from operations – reinvesting the entire business’ cash flow into the buildout.

In short, it’s leveraging the company on this bet. The spending will certainly provide incremental growth uplift, but if return on investment falters, forward earnings will be blanketed with the long and lagging drag of depreciation for years with little to show for it. If Microsoft’s hesitance proves wise, there is significant downside risk in the stock.

Historically speaking, ORCL hasn’t needed to rely on aggressive capex, so the current bevy of moves smacks of desperation. I see this aggressive business pivot towards growth-at-big-cost to be a misguided departure from the mature tech-giant playbook which generally includes inorganic growth at reasonable hurdle rates and a lot of buybacks.

Broadcom Inc. (AVGO)

As a major component supplier to datacenters, Broadcom has ridden the AI capex wave, but unlike NVDA which has seen its forward valuation metrics rapidly compress to cycle lows, AVGO’s forward metrics expanded significantly since 2023. On a NTM basis, AVGO trades at double its historical multiple and a 20% premium to NVDA.

While much of the company’s recent growth has been driven by US datacenter builds, AVGO’s business is much broader, with exposure across a range of applications and end uses. The company also has significant revenue exposure to China (and Singapore as a proxy), which could present challenges given the geopolitical landscape. Meanwhile AVGO faces competitive pressures within the AI market as recent news shows Google shifting towards MediaTek to help design its Tensor Processing Units (beginning with next generation designs in 2026).

Long-time CEO/Architect Hock Tan and AVGO management are well aware of their saturated position in the communications chip and embedded interconnect markets, so much so that they have made it a point to use cash generated by the chip business to expand into other verticals. The company went on an acquisition spree between 2018 and 2021, spending more than $110 billion on three software companies, with the bulk of that being on virtualization giant VMWare.

While virtualization is clearly a winning theme in the distributed, heterogeneous computing world, Broadcom is running the subsidiary as if it were a private equity firm, raising unit prices by 1,200% in some instances and increasing minimum core purchases from 12 to 72.

A slowdown in AI spending or sentiment could lead to significant multiple contraction, while its broader business portfolio demonstrates significantly slower growth with global macroeconomic sensitivity.

AI Coattail Riders

Many names adjacent to AI infrastructure have ridden the trend as investors scrambled for any hint of companies utilizing AI in a manner that demonstrably increased revenue. This frenzy to own “AI implementers” has handily overlooked the fact that AI itself poses an existential risk to these businesses. Operating in areas that can quickly be commoditized (thanks to current struggle to generate ROI in AI outside supplying the data centers), these companies are pitched as the “scaffolding”. Perhaps investors have forgotten that the scaffolding is dismantled and hauled away once the building is constructed…

Innodata Inc (INOD): Assisting in One’s Own Demise

Innodata’s core business is paid data grunt work: armies of offshore staff label images, transcripts, medical notes, and code snippets so that clients can train or fine-tune large models. The company wraps this labor in basic workflow software, then markets the bundle as “AI data engineering.” No wonder investors have flocked to the stock - after all, inno- + -data. What a winning combo for the AI era.

Innodata’s revenue spiked to about $59 million last quarter, EPS turned positive at $0.34, and operating margin hit 19% — nice optics, to be sure. But investors appear to believe the company is a picks-and-shovels royalty on generative AI demand rather than a people-per-hour, overearning contract services shop that is easily disintermediated by the very technology that has caused its earnings to spike.

INOD trades at more than 6 times sales, roughly in-line with Salesforce (CRM).

That premium ignores how easily the service can be replaced even if AI demand explodes. Hyperscalers and foundation-model labs are moving labeling in-house, using active-learning loops that cut human clicks by 70 percent. Open-source tools like Label Studio and commercial platforms such as Scale AI make it trivial for customers to spin up their own pipelines. On top of that, synthetic data generation and self-supervised techniques keep reducing the need for meticulously hand-tagged datasets.

Eighty percent of run-rate revenue comes from one hyperscaler, and the rest is “lumpy” by management’s own admission. Additionally, the model depends on thousands of offshore annotators, so wage inflation flows straight to cost of goods. Scale AI, Appen, and in-house labeling tools from the same hyperscalers are undercutting bids every quarter, crimping price and capping margin.

If that flagship customer trims volumes by even 20%, the promised 40% growth in 2025 vanishes, EBITDA could halve, and a services multiple of three times sales puts the stock in the mid-teens. Unless Innodata lands new whales fast or proves it owns defensible tooling rather than interchangeable labor, investors are paying a SaaS valuation for a business that can be automated out of existence.

Another example of this ironic setup is…

Intapp (INTA): Commoditized Offering, Differentiated Valuation

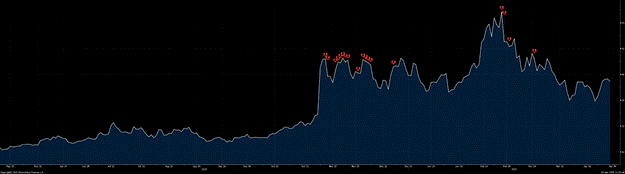

Take, for example, IntApp (INTA), which has risen 500% since 2022 lows despite just a ~50% increase in revenue.

Intapp sells cloud workflow tools to law firms, private-equity shops, and consulting partnerships. Management touts “AI-assisted knowledge management,” yet the letters AI appear far more often in the marketing deck than in the income statement. Even so the stock changes hands at about 9x sales and roughly 44x free cash flow—a richer multiple than ServiceNow commanded at the same size. Net cash is thin, and the company still reports GAAP losses. The bull case says legal and deal advisers cannot afford not to “AI-up,” but legal startup Harvey will likely surpass INTA’s SaaS ARR this year and make it clear that they hardly have an edge.

Don’t get me wrong, these are both businesses that I’d love to have operated for the past couple years. They’ve benefitted hugely from the demand for AI. But, as an investor, the terminal value proposition is dismal. The C-Suite will walk away having paid themselves handsomely for being in the right place at the right time, and investors will get shafted as the companies are relegated to the stock market equivalent of that cardboard box in your garage with all the power adapters for old cable boxes and first generation iPads. We can see that playing out in the insider transactions for INOD already:

Healthcare AI Hope Trades

Both GE Healthcare (GEHC) and Veeva (VEEV) have been bandied about as “AI winners” in the healthcare industry. While the outlook for AI deployments remains dynamic and could certainly accrue to the benefit of these companies, there is nothing material in the near-term, and in the meantime, both have seriously challenged core businesses.

In the case of GEHC, the company supplies capital equipment such as imaging machines and patient monitoring systems to hospitals and other healthcare facilities. A double-digit percentage of their earnings comes from China, putting them squarely in the middle of the trade war, and the bulk of their US business comes from hospitals that face a significant risk of funding cuts under the Trump administration.

Meanwhile, VEEV, a software company, sells technology to drug developers to help manage trials. While drug development activity is picking back up after a long lull, the timing of this rebound is in question, and in the meantime, VEEV faces significant competitive pressure from larger players like Salesforce (CRM) as well as from internally developed solutions from their customers.

Another Healthcare AI hopeful, Doximity (DOCS), is trading near an all-time high selling technology solutions that help pharmaceutical companies market their products to doctors. Not only is this a challenging business with significant potential competition, but pharmaceutical advertising is in the crosshairs. The Trump administration has spoken directly about limiting how the industry markets, but more importantly, a slew of negative potential policy actions, including tariffs targeting the industry and tax reform, will impact bottom-lines in the pharmaceutical industry and, as a result, advertising budgets. This puts DOCS revenue at significant risk.

Below the Paywall: Policy and Market risk to define 2025 and 40 more single stock discussions.