The Tale of Two Chinas

#89: The Bullish Case from a China Bear

Back in June 2021, I started writing about the mounting stress in China’s financial system, which I collated into a “China Credit Thesis”. The argument was both tangible and systemic, and most certainly dramatic. In short, I suspected that the Chinese economy was on the brink of turmoil. It went like this.

For the past 25 years, since the liberalization of the country’s property laws, much of China’s tremendous growth has been driven through property and infrastructure development. Local governments raise funds by selling state owned land to property developers. Developers build concrete compounds to house the country’s massive urbanizing population, while governments build the infrastructure to support it. All of this has been funded through the massive expansion of credit.

As a result, property is central to the Chinese economy - far more so than in other countries. Property values make up the vast majority of citizen wealth. Property development creates employment in construction and supports a wide range of upstream suppliers, from raw materials to finished goods. Banks provide massive loans to this industry. For all of these reasons, property was considered by most to be too big to fail, which actually added to its investment appeal.

This development model worked for two decades, outlasting many accusations of a

“housing bubble”. But while new housing developments helped achieve top-down economic targets, the actual economic benefit of endless empty flats was rapidly diminishing. Simply, the country did not need any more housing and desperately needed to redirect its investment into more productive avenues. Further, the growing piles of debt across developers, banks, local governments, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) was endemic and problematic, enabled by the moral hazard of longstanding government support.

This was the tale of two Chinas.

From the outside, China appeared to be the ascendant superpower. Internally, the model of growth was broken.

Breaking the Backstop

The key to the China Credit Thesis was not a market-based analysis of debt ratios or sustainability. Rather, the façade of growth could continue on so long as it continued to be blessed (and backstopped) by the government.

Rather, the critical shift was a policy decision. Beijing seemed intent on reforming its property sector and debt markets with more than just words.

Throughout late 2020 into 2021, various banks, property developers and state-owned enterprises began defaulting on loans. This was very unusual. Historically, such defaults were exceedingly rare and most debt in the country was priced with very little credit risk as a result. The working assumption was that all state-owned or systemically important borrowers enjoyed an implicit government backstop. Growing credit stress in financially significant industries like banking or property would raise concern in any economy, but in the context of China’s growth and debt model, the deeper implication was profound.

Allowing the failure of rural banks like Baosheng, or extreme distress in state-owned Huarong, revealed a new era of Chinese policy within the financial sector. More significantly, the Three Red Lines policy established in August 2020 halted the flow of new credit to property developers. For developers that were reliant on ever growing debts to remain liquid (which most were), the Three Red Lines was a death sentence.

This gambit was both necessary and deeply risky. Investment needed to shift into more productive ventures. But removing the backstop in a massively over-levered economy that had ignored credit-risk for years, could result in a massive, sudden repricing of credit and asset prices with potentially explosive effects.

By the summer of 2021, the Three Red Lines claimed its first major victim, property developer Evergrande. The significance of Evergrande was not just in the demise of one massive, highly-distressed company, but rather in the authorities response.

There was no response.

Contrary to the vast majority of opinion at the time, there was no bailout for the company. Its owners or creditors would likely receive nothing. The implication was massive for the rest of the property market. With any implicit backstop severed, funding channels froze, and the property market began to tumble. I argued in September 2021 that contagion was rapidly spreading and nearly every other property developer would soon suffer the same fate as Evergrande.

And they have.

Since then, we have seen near total losses in property sector stocks and bonds, while the underlying property market remains under deep pressure. As one example, below is the equity and debt of Country Garden — an investment grade rated developer at the time of Evergrande’s failure, whose offshore bonds trade today at eight cents on the dollar.

While it may seem reductive to simplify an entire country’s economic fortunes to a single industry, I think it’s almost impossible to overstate its importance. Below is Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index (HSI) in blue, a broad Chinese property ETF in orange, and an index of residential property prices in green.

Financial Contagion

Even as the demise of the property sector seemed inevitable, a larger risk loomed. Would the enormous liabilities of these companies pose a systemic risk to the financial sector? Would Local Government Financing Vehicle (LGFVs) debt — which replaced land sales as a source of regional financing — eventually break? Would the government’s indifference to the developers extend also to struggling banks?

Objectively, the massive exposure to property debt and inevitable credit losses seemed insurmountable for a transparent and market-based banking system. And while the Chinese system was neither of these things, authorities had already shown a willingness to rely on market-based solutions for struggling financial institutions.

Throughout late 2021 and 2022, I argued that the risk to the Chinese financial system was high, but I ultimately laid out two possibilities:

Contagion in the financial system could lead to a sudden “crisis”

Alternatively, if financial distress was contained, the country would merely have to contend with a dramatic growth slowdown as the illusion of property wealth faded and the economy pivoted its investment into more productive sectors

And for a while there were plenty of signs of stress in rural banks particularly in the summer of 2022 (#13: Dominoes). I’m still of the opinion that a whole slew of banks are probably insolvent if they were held to transparent market standards. But as of this writing in January 2024, a financial crisis has not occurred, even as claims on property circle the drain towards zero and LGFVs struggle with repayments.

In my opinion, this is also a policy decision.

It’s possible that some sort of crisis is still on the horizon — perhaps spurred by LGFV defaults, or simply the mounting strain of bad loans. But my thinking has genuinely shifted over the past year. In March 2023, I wrote about a quiet but massive liquidity injection into a list of the most at-risk banks, and noted how the opacity of the system reduced the likelihood of contagion (#48: See No Evil).

Further, while many have suggested that the large PBOC liquidity injections over the past year have failed to spur consumer confidence or demand for credit, their purpose was more likely to support the banking system itself.

Of the two alternatives, (1) sudden crisis or (2) painful slowdown, the former seems more likely — and perhaps much of it has already taken place.

In Hong Kong, the total value of the offshore stock market has fallen by 46% since the summer of 2021. Onshore, the A-share market has fallen by 40%. Property values have taken a big haircut. Consumer confidence is already in the tubes. If the financial system remains intact, what shoe is left to drop?

Two Chinas

In January 2024, the tale of two Chinas has reversed. Rather than an ascendant and unstoppable economic force, China is now described as a withering — destined to decline due to demographics, de-levering and de-globalization. And while conventional wisdom once argued that central backstopping removed all credit risk, we now hear that policy and stimulus is entirely incapable of halting the current economic slump.

The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

China’s challenges are real, but are now widely recognized and to some extent must be reflected in asset prices. But more importantly, the property growth model that created the illusion of economic ascendency was actually a dead-end. Curbing the property bubble was a painful but necessary top-down policy decision, paving the way for more productive growth in the long-term.

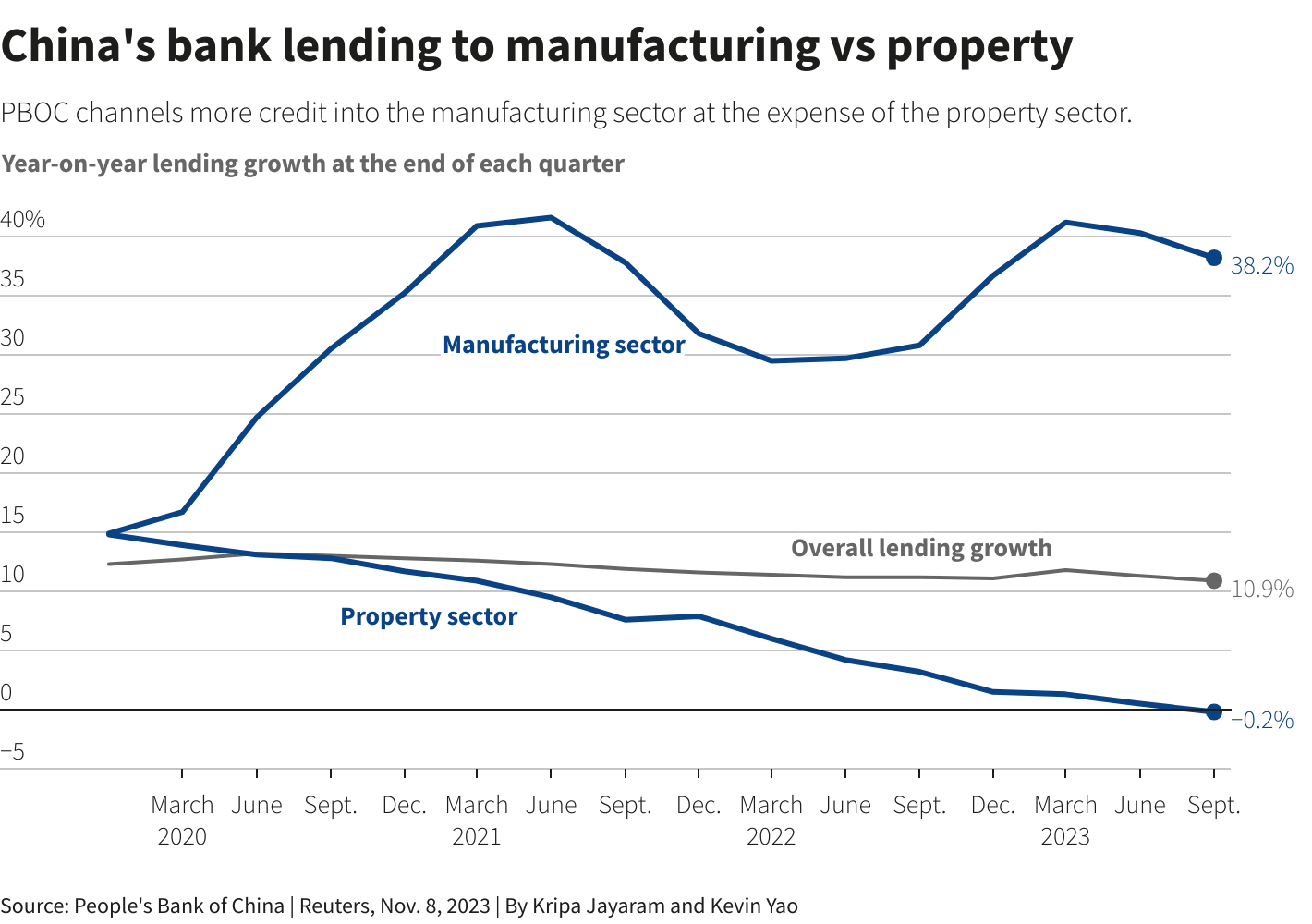

Already, we see a huge shift in new credit away from property and into (advanced) manufacturing.

Meanwhile, for all the discussion of de-globalization, Chinese exports in RMB terms are still 32% higher than before COVID, even as its stock market has plunged.

In an interconnected global economy, China is simply too big and too important to meaningfully de-couple from global growth.

Consider Apple — with its growth-y $3.0 trillion market cap — which manufactures 95% of its products in the country.

Or consider Tesla. The Shanghai factory was transformative for the company, in terms of its rapid construction, quality of output, and profitability. This stands in sharp contrast to the challenges of expanding production in the U.S. or Germany. In this week’s 4Q23 earnings call, Elon Musk spoke bluntly about Chinese auto competitors:

“Chinese car companies are the most competitive car companies in the world. So I think they will have significant success outside of China, depending on what kind of tariffs where trade barriers are established. Frankly, I think if there are not trade barriers established, they will pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world. So they're extremely good.”

While Musk is clearly angling for a self-serving tariff, the underlying point should still be taken seriously.

Even as its labor costs have risen and some lower value-add manufacturing has diversified throughout southeast Asia, the scale and existing supply chains within China make any true “decoupling” incredibly challenging if not impossible.

It just seems somewhat foolish to dismiss the country’s enormous industrial base, human capital, and growing technological advancements.

Market Considerations

For the first time, I’ve become optimistic on the outlook for Chinese equity markets, and included the Hang Seng index as a winner in my 2024 Macro Outlook. The rationale was both tactical and fundamental, if somewhat speculative.

Tactically, when China equity routs start to make international headlines, it has generally been a good time to buy (see March 2022 or October 2022). As the HSI faded back towards the October 2022 lows, a rebound seemed more likely. Such rebounds have been fast and furious historically.

Further, China is not the only country with economic uncertainty. Nevertheless, China’s stocks continue to plumb new lows at a time when every other stock market globally is reaching new highs.

The fundamental rationale is what I laid out above. Having watched the property collapse already unfold over the past two years, what is left to give? I have to believe that an investment in China presents a better risk/reward today than in 2021. Assets are half price, and the property bubble has been significantly deflated.

Another point to consider is currency and monetary policy. An easing Federal Reserve should take some pressure off of the yuan, and provide the PBOC more leeway to ease with less risk of further devaluation1.

Catching a falling knife is always risky, and since publishing the Macro Outlook on December 22nd, the HSI is down 2.4%.

But the dive to 15,000 this week prompted the announcement of several major stimulus measures, including $278 billion worth of direct stock market intervention. It remains to be seen whether this is the start of a sustainable rebound, but it does seem that the government is putting increasing muscle behind stabilizing the financial market, which can only be viewed positively.

Risks

The key risk is simply that downward momentum continues. That the stock market, the property sector, financial sector, and broader economy continue to fall. The financial crisis that I argued for in the past may finally come. Indeed, it would be poetically ironic if I threw in the towel just in time for the final flush.

A remote risk is extreme geopolitical tension or war. Investments in foreign adversaries tend to be hard to recoup. But it’s also worth considering what this situation would imply for the value of other equities around the world…

Conclusions

The key insight of the China Credit Thesis was that the country had chosen a new path forward. It would pivot away from unproductive property development while attempting to reduce moral hazard in its financial markets.

At a minimum, the pivot would result in painful deleveraging, slowing growth and asset devaluation. At worst, it could prompt a financial crisis.

So now, after enduring several years of pain, has China’s more prosperous future arrived? The market certainly doesn’t think so. Throughout the process, the external narrative on the country has transformed from unstoppable to uninvestable. As for me, I’m not sure. But for the first time, I’m feeling optimistic.

Thank you for subscribing to The Last Bear Standing. If you like what you’ve read, hit the like button and share it with a friend. Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

TLBS

Though admittedly this lever is more speculative.

Liked it!!

I am much more bearish on China. Savings in the economy exceeds 40% of GDP. In the past, the savings have mostly funded housing and infrastructure investments. Housing is obviously in the doldrums, but I think infrastructure investments are the next shoe to drop. Many LGFVs have debt/EBITDA multiple in the teens. Their financials make US HY corporate issuers look good in comparison. And local government finances have been permanently weakened by the weak housing demand. The decline in infrastructure investment will have as big a macro impact as the housing downturn.