Dominoes

#13: On Bad Debt and Chinese Banks.

This week’s post is the second half of a series on China’s property and debt crisis. Last week’s post provided background on the topic if you missed it!

But first, some good news and bad news. The good news (for me) is that I’m getting married next week. The bad news (for you) is that there will be no post next week, but TLBS will be back on August 5th.

Bad Debts

When I first wrote about the risk in China’s credit markets in June 2021, the property sector was still humming along. Before Evergrande’s failure grabbed headlines around the world, I was focused on a different distressed name, China Huarong Asset Management (“Huarong”).

Earlier in the year, Huarong made a surprise announcement that halted its stock trading and sent its debt spiraling. It was unable to produce audited financial statements for 2020 by its April deadline, signifying deep trouble with the company’s financial reporting and viability.

Huarong is the largest of four state-controlled asset management companies (“AMCs”) created in the wake of the Asian financial crisis of 1997 to absorb and unwind bad debts from the banking system. Often called “bad debt banks”, these entities are the garbage disposal of China’s financial system. In theory, they purchase bad loans from banks and seek recovery through restructuring or asset sales. In practice, they have expanded far beyond their initial mandate and engaged in the exact sort of risky lending that they were created to clean up.

In other words, the garbage disposal was clogged, chock full of bad debts of its own. Who do you call when the cleanup crew makes a mess?

While causalities of China’s de-leveraging campaign had been piling up for years, Huarong was a new and important casualty.

First, it showed how pervasive bad debt had become in the banking system, not just in small rural banks but at high-profile state-controlled entities. But more important was the market’s reaction to the news.

Trading of the company’s stock was halted, and the value of Huarong’s onshore and offshore bonds plummeted. The amount bondholders could borrow against the bonds in the repo market was cut in half1. Credit spreads on the other AMCs widened, and the companies began to publicly worry about their ability to tap USD funding markets.

Huarong dangled in the wind for four months until eventually central authorities announced a $8 billion rescue plan in mid-August. Although the rescue plan only amounted to about half of the reported losses from the prior year, it was enough to restore some confidence for a time.

Despite the partial rescue, the saga provided a real world template of what would happen if a systemically important, state-controlled financial entity found itself in trouble. Traders would panic, the value of the debt would plummet, fear would spread to other firms, and Beijing would have no immediate plan to address it. In other words - classic contagion. This got my attention.

Then, the property market crashed.

Dominoes

The summer of 2021 was critical for the future of the property sector. Like Huarong, the downfall of Evergrande provided an important template of what would happen when a major property developer faced liquidity issues. But unlike Huarong, there would be no bailout.

By September, a chain reaction had begun that, in my opinion, seemed near impossible to stop.

Evergrande’s failure put a deep chill over the entire property sector. Sale volumes were crashing and financing was drying up, putting huge liquidity pressure on other developers who were only marginally more healthy than Evergrande. These circumstances would lead to a the widespread and indiscriminate failure of property developers. So-called “good” companies would prove to be no different than the “bad” ones.

The failure of property developers would lead to massive losses in the banking sector which had enormous exposure to the sector and already stood on shaky footing. Eventually, the property crisis would lead to the failure of one or more banks. This final domino - the spillover from the property market to the financial sector - would tip what may otherwise have been an extended economic hangover in China into a financial crisis akin to the US subprime crisis of 2008.

Today, in hindsight, we can say with certainty that Evergrande sparked a contagion that led to the widespread and indiscriminate failure of both “good” and “bad” property developers, leaving behind a mountain of bad debts and unfulfilled obligations.

Will the next domino fall?

Liquid or Solvent

There are two distinct elements to financial viability: liquidity and solvency.

Being liquid means that you have the cash you need to operate the business today. You can pay your bills.

Being solvent means that you will eventually be able to repay all your debts, or that your assets exceed your liabilities.

While both elements matter, liquidity is much harder to fake. Determining solvency, however, requires forward looking assumptions that are easy to manipulate and are harder for an outside observer to disprove2.

The property developers that have failed have been insolvent for years, they just lied about it. Evergrande never reported a loss and its balance sheet showed that current assets exceeded its current liabilities. This farce continued because the company had liquidity through financing channels. When the liquidity dried up, the charade was over.

The same concept applies to banks.

Given the massive exposure to the collapsing property sector and the history of grossly underreported non-performing loans, it is likely that some Chinese rural and midsize banks are insolvent today3. Of course, none will admit this reality, and it is nearly impossible for an outsider to determine independently due to lack of clear and reliable information. It is only once these banks become illiquid that their insolvency becomes unavoidable. A bank failure will not happen based on a reasonable expectation of future losses, but rather, it will happen when one runs out of money.

Pressure on rural and midsize bank liquidity is growing4.

Every loan that goes unpaid puts liquidity pressure on banks (even if it is “extended”). A year ago, the list of delinquent borrowers included just a handful of developers, but now it has grown to include nearly all of the largest developers, their suppliers, and homebuyers.

In recent weeks, owners of unfinished apartment projects have begun to organize mortgage boycotts that have quickly spread to over 300 projects in 90 cities and are estimated to involve mortgages worth 2 trillion yuan. This is a startling new development that prompted an emergency bank meeting with regulators. So far, banks are being asked to provide even more funding to bankrupt developers in order to help keep construction going. As construction at projects stall, this problem only grows.

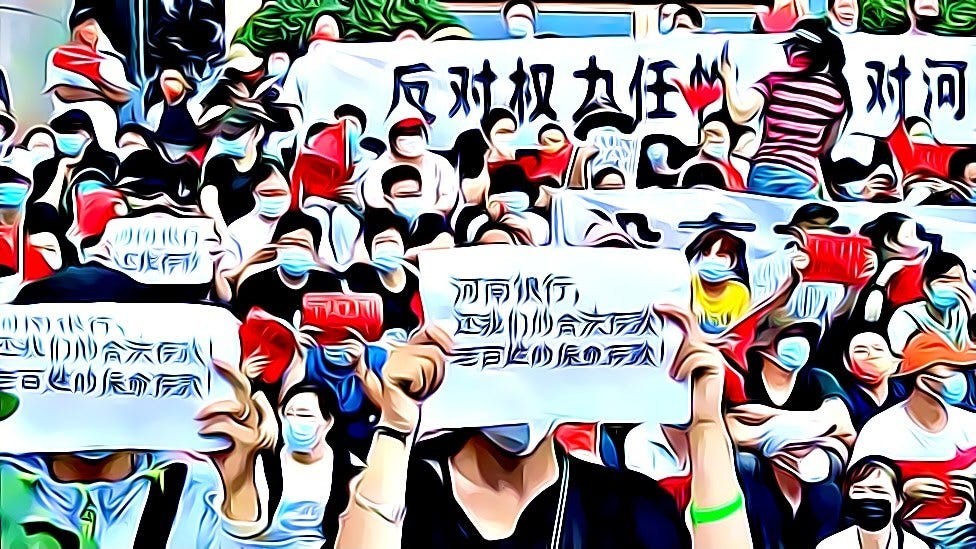

Liquidity pressure can also come from the depositors. If individuals become concerned about a bank’s health (perhaps due to a rapidly expanding mortgage boycott), they will try to pull out their money. Glimpses of this phenomenon were visible recently as depositors protested outside several rural banks in Henan after being denied withdrawals since April5.

Finally, when other banks become concerned about a bank’s health (perhaps due to a rapidly expanding mortgage boycott and a bank-run of depositors), they will stop lending to it in the interbank market.

Then, the bank fails.

The Prognosis

In plain English, what do I expect to happen next?

Here are some high-confidence working assumptions:

The Chinese banking system is overrun with bad debt and non-performing loans, which are mostly hidden from regulators and public investors

Property represents the largest exposure of banks. Rural and mid-size banks have the highest exposure to the worse property markets

More developers and their suppliers will default and the cumulative weight of their delinquency will put pressure on banks

Mortgage boycotts will continue to spread - people will not pay for houses that don’t exist

Central authorities have no “master plan” to address these problems

Based on these assumptions, the following conclusions are likely:

Faith in at-risk banks will continue to erode leading to further liquidity pressure from depositors and lenders

Some banks will fail

The remaining question is whether a failure will happen at a large enough bank to create panic in the financial sector. My best guess is yes.

Remember Huarong? The “bad debt bank” was clogged with its own bad debt prompting a too-big-to-fail scare before the property downturn even began. This year, a second AMC, China Great Wall Asset Management, failed to produce an audit as well. USD bond yields on both companies are approaching 10% - a large spread implying significant credit risk.

Meanwhile, many publicly traded banks stocks are at or near all-time lows. Even the major state-owned banks have continued to trend lower and are now trading at 0.3x of book equity on average, considerably lower than prior periods.

While trying to pinpoint the weakest link is next to impossible, there are a couple to keep your eyes on - national banks smaller than the state-owned conglomerates but large enough to ripple through markets such as Minsheng, Everbright, Bohai, and Ping An.

It’s also possible that trouble could originate in an non-bank financial sources - insurance products (think AIG), shadow banks, wealth management products to name a few. There are no end to risks in this high-stakes game.

Banks are now contending with an uncontrolled implosion of their largest borrowers, a revolt from mortgage payers and a bleak, slowing economy overall. It won’t be an easy path forward, and there will be more casualties.

The chain reaction is in motion, the last domino will fall.

If you are a bank or another financial institution who owned some of Huarong’s $18.5 billion worth of onshore bonds, you can use those bonds as collateral for short term borrowing in repo markets. The bonds can provide immediate liquidity access to holders without ever being sold. After Huarong failed to report, the liquidity available to those holders was cut in half, or about $9 billion of potential liquidity disappeared in aggregate. If someone was reliant on this liquidity, this would be a problem.

One purpose of accounting, audits, and regulatory oversight is to ensure that solvency determinations are appropriate.

In other words, a reasonable estimation of future losses would exceed the equity capital of the bank.

It’s worth noting here that the PBOC has provided ample liquidity injections into the system in 2022. This has driven down short term borrowing rates for the largest banks and gives the impression of ample liquidity. While this may be true for the largest banks, there are thousands of smaller banks that rely on the lending from larger banks. In other words, there may be enough money in aggregate but that doesn’t mean everyone has it.

Though the issue at these banks was graft rather than property defaults.

Congratulations to you and the soon to be Mrs. Bear!

Phenomenal work.