Playing the Pivot

#79: Is it time to bet on falling rates?

Every economic cycle is different. This time around, the most underappreciated risk in the financial world was duration — the sensitivity of asset prices to changes in interest rates. Outside of speculative junk, the worst performing investments in this aggressive hiking cycle have been those with the most direct interest rate risk — even those considered “safe” from a credit perspective.

I hope that my writing here over the past two years has highlighted the risk of duration and has avoided the temptation to prematurely call for a reversal in rates. Even as the pace of rate hikes slowed, the steepening in the long-end of the yield curve continued to inflict losses on long-duration assets for most of this year. But the situation today is evolving.

The broad consensus is that recent economic data have nixed the slim odds of any further rate hikes. This week, soft CPI and PPI prints, combined with the gradual erosion of the labor market show the ongoing balancing of the Fed’s dual mandate1. Having already delivered on a 5.30% hiking cycle, pushing interest rates across the curve to the highest level in 15 years, the question of credibility is also less pressing. The Fed’s most reliable mouthpiece at the Wall Street Journal has confirmed the central bank’s plans to hold the current pause.

The market is now considering the possibility of rate cuts as early as 1Q 2024 and expects over 100bps of total cuts by the end of 2024. If this path proves correct, there are major implications for long-term interest rates and asset valuations.

Historically, in periods of either secular inflation (1960 - 1982) or disinflation (1982 - 2020), the local peak in the federal funds rate has tended2 to coincide with the local peak in long-term rates. In other words, when the Fed shifts from hikes to cuts in the policy rate, long-term rates tend to fall as well.

The obvious question, if we assume the future path of interest rates is lower, is how to play the pivot? And the obvious answer is to look at the assets that have been most negatively impacted by rate-hikes to date.

This week, we consider the risks and opportunities in government bonds, commercial real estate, banks, and utilities.

Government Bonds

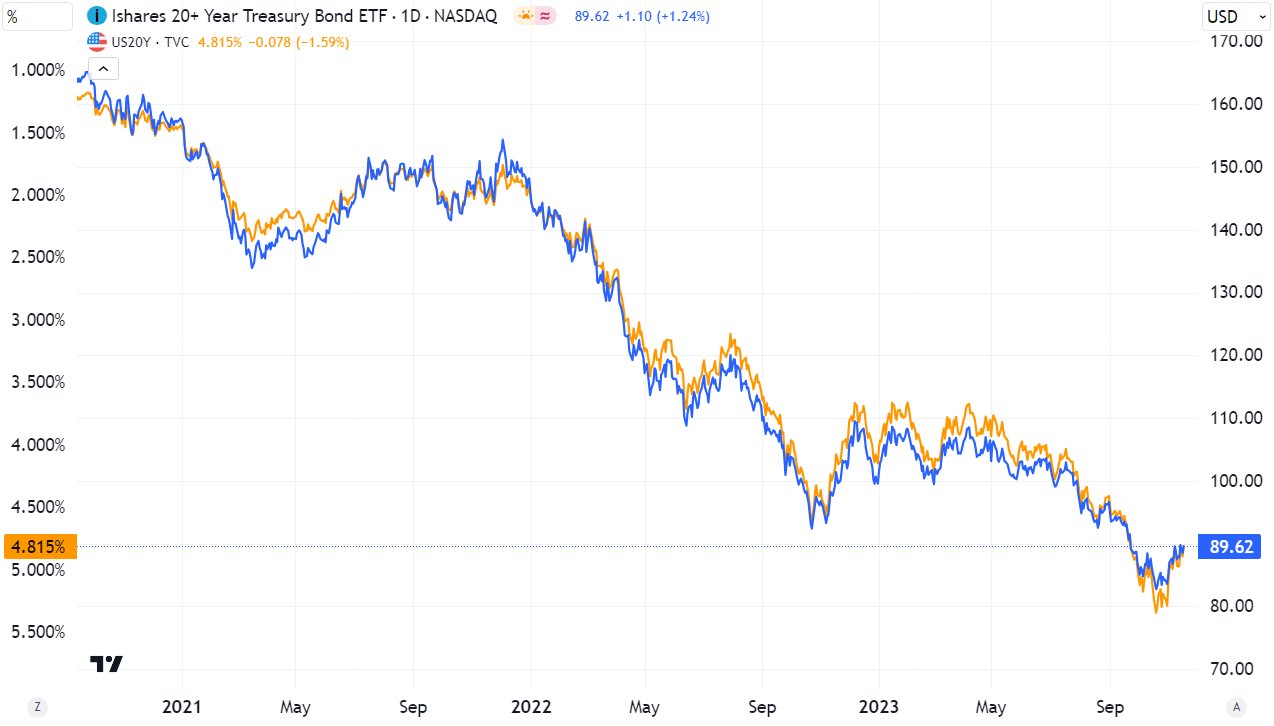

The most obvious and direct exposure to duration is in long-term government bonds. As bond math dictates, market value moves inversely yields, and therefore long-term bonds provide one of the simplest and actionable exposures to interest rates. Shown below, the most popular long-term U.S. government bond ETF, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) necessarily trades in close tandem with long-term yields.

I should emphasize how significantly the risk/reward in long-term government bonds has evolved over the past several years.

Back in 2020, these bonds provided a paltry 1.00% of annual interest income with duration rate skewed almost entirely to the downside. Today, that income has increased to 4.8% annually with duration risk that skews to the upside given the current rate cycle and the highest bond yields in well over a decade.

Here is some quick-and-dirty napkin math for investment returns in TLT. Every +/- 50bps move in long-term yields is good for a -/+ $10 move in the ETF. For example, if long-term rates fall 150bps over the next year, the market value of TLT will increase ~$30 from $90 today to $120, or a 25% gain on principal3. When combined with almost 5% in interest income, total returns pencil to nearly 30%. Of course, negative duration risk still exists (yields could rise from here), but the positive real interest today helps mitigate this downside.

Another key attribute of government bonds is that they benefit in economic downturns both as a “flight to safety” and the beneficiary of counter-cyclical monetary policy. If soft-landing hopes fade to hard-landing pessimism, not only will investors crave this safe asset but the largest single market participant - the Federal Reserve - may transition from a seller to a buyer.

Overseas, more exotic duration plays exist. Longer tenors and lower coupons increase the bond’s sensitivity to interest rates. Consider the famous 100-year zero-coupon Austrian bonds, 40-year UK gilts, or 50-year French OATs (pictured below). While the market value of such bonds have been crushed over the past two years, these securities provide the most dramatic upside if interest rates fall.

I should note that the interest rate, inflation, economic, and FX dynamics vary from country to country, adding complexity to these securities. While interest rates in Europe have not risen to the same degree as the U.S., the post-COVID European economy has also struggled to rebound. With a more fragile economy and interest-rate sensitive housing sector, it’s possible that cuts in the European rates are more significant.

While such bonds provide the most levered exposure to falling rates, and should perhaps entice sophisticated investors, they are also less liquid, more complex, and probably not actionable for everyday folks.

Commercial Real Estate

Back in April, I analyzed Vornado Realty Trust (VNO) as a window into the office CRE market. My conclusion was surprisingly sanguine:

Is urban office CRE the next shoe to drop? For many, the losses have already been felt… The equity owners of these assets, such as REIT common holders and sponsors, have also already borne massive losses in share price, based on a lower expected long-term residual value of the assets… For a long-term investor, perhaps some of the equity values today may prove to be attractive entry prices.”