Bonds of Mass Destruction

#22: On Duration and Value Destruction.

This week, London regained its crown as the center of the financial universe, though not under the most flattering circumstances. First came a brief currency crisis as the pound (GBP) careened towards dollar parity on Sunday night (trading as low as 1.05x, though since rebounding). Then on Wednesday, a liquidity crisis in the U.K. government bond market (known as gilts) forced the Bank of England (BoE) to intervene with emergency not-Q.E.

The dysfunction in the U.K. financial markets did not emerge suddenly, but rather was the slow brewing consequence of monetary and fiscal policy which finally bubbled over.

The GBP has been sliding against the dollar for well over a year, accelerating since the U.S. Federal Reserve began its aggressive hiking cycle in March. Meanwhile, the BoE’s intervention to restore liquidity and cap losses in the gilt market was the predictable outcome of a global quantitative tightening - and coincidentally was the focus of last week’s post, The Furnace.

Most commentary this week has centered on the current predicament of policy makers. However, a topic that deserves equal consideration is the importance (and risk) of duration.

If you are are financial professional or even a casual observer, you probably know the term and its common use. But duration is one of those technical terms that has lost its specific meaning as it is applied more broadly in non-technical ways (such as to describe tech equities1).

Duration is not a qualitative term to describe any investment with “long-dated cash flows”. Duration is a mathematic calculation of the weighted average life of the present value of a bond’s cash flow, and it determines that bond’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates.

Duration is also one of the most overlooked risks in the present financial markets.

Let’s explore.

Duration

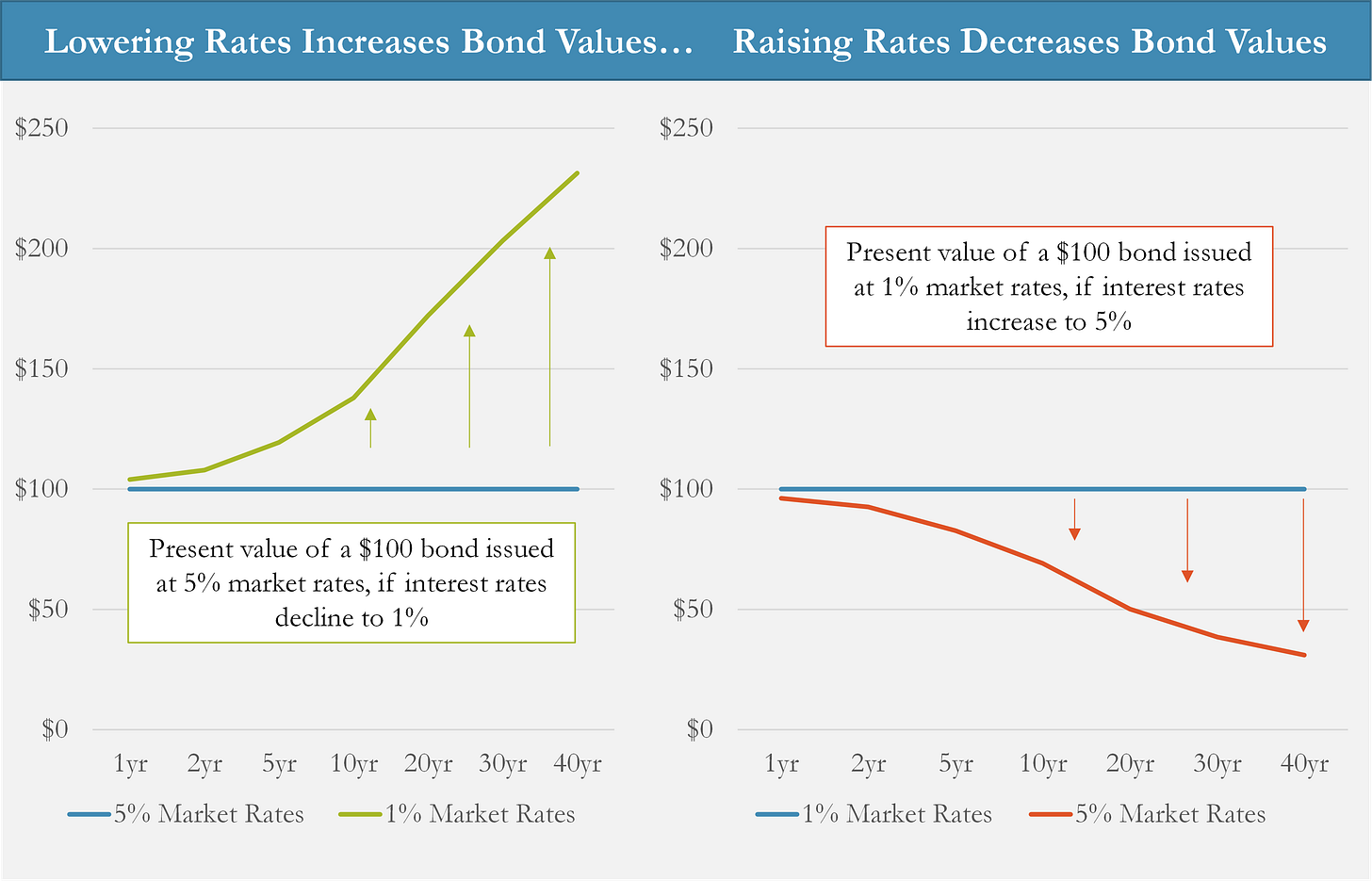

We know that if market interest rates decrease, the value of a bond will increase (other things equal). Meanwhile, if market interest rates increase, the value of that bond decreases.

But knowing the term of the bond is not enough. Duration is the critical computation that determines exactly how sensitive a bond is to changing interest rates.

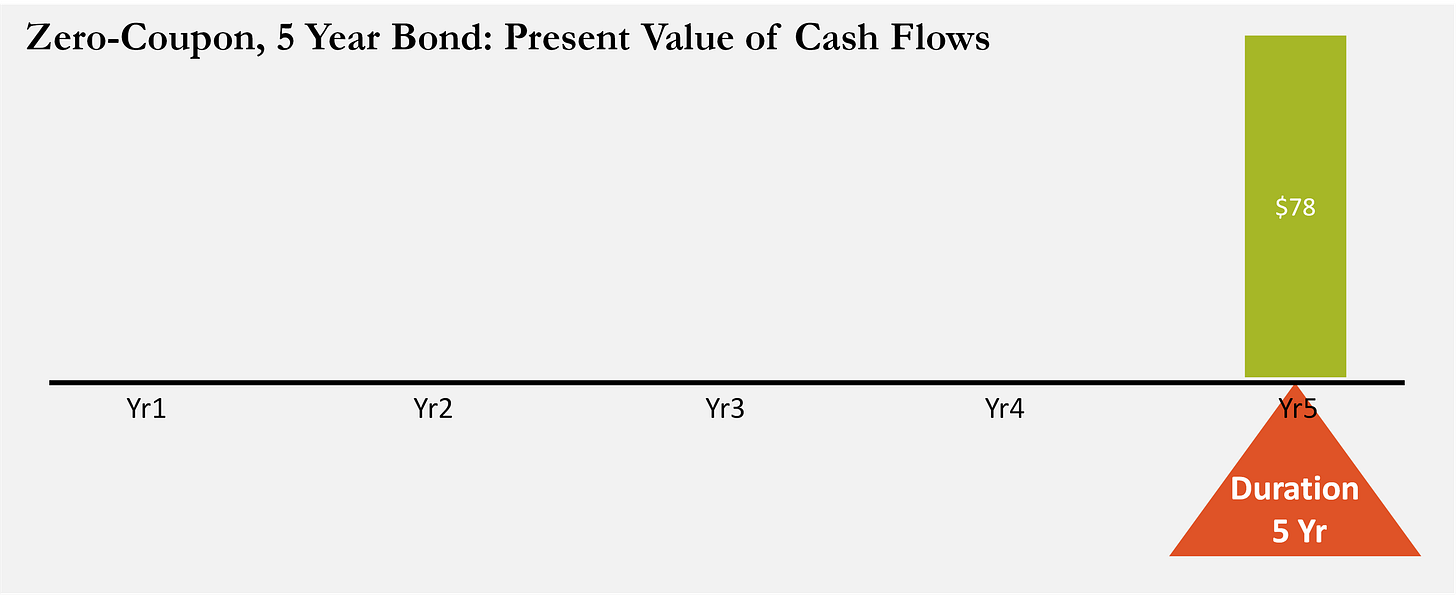

Here is a visual that helps me conceptualize duration.

First, consider the nominal cash flows of a 5-year $100 bond with a 5% coupon. The holder of the bond will receive $5 of interest every year, as well as the return of the $100 principal at maturity in year five.

We know that cash today is worth more than cash tomorrow, and so we must take the discounted value of those future cash flows, to calculate their present value. The further away the cash flow, the less it is worth today.

Assuming that market interest rates are 5% as well, the present value of this bond’s cash flows looks as depicted below.

If you imagine all these cash flows are weights suspended on a flat board, duration is the fulcrum that balances the board2. The duration of the bond presented above is 4.5 years - fairly close to the largest cash flow at the bond's maturity. Duration measures the weighted average length of the investment in present value terms.

The simplest example is in a zero-coupon bond - a bond that has no interest payments and only repays principal at maturity. For a zero-coupon bond, the duration will always be equal to the maturity, the only period in which there is a cash flow.

The duration of a 5-year zero-coupon bond is 5 years. But duration (other than for a zero-coupon bond) is not a fixed number, but instead fluctuates based on market interest rates.

ZIRP

There are many consequences of the Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) that has been adopted by central banks globally since 2008. One obvious effect is the appreciation of financial assets. Bond values increase as rates decline, housing prices go up as mortgage rates drop, and equities rally both due to lower rates and the liquidity benefit of Quantitative Easing (QE).

A less appreciated consequence is the effect on the duration of the global aggregate bond market. For one, investors may voluntarily seek out longer term bonds because they provide slightly higher yields than the near-zero rates on the short end. But more importantly, the duration of a fixed maturity bond increases mathematically as market interest rates drop.

A 40-year bond with a 10% coupon, issued when market rates are also at 10% has a duration of just 10.8 years. However, a 40-year bond with a 1% coupon, issued when market rates are also at 1% has a duration of 33.2 years3.

The lower the rate regime, the longer the duration, and the greater sensitivity those bonds will have to changes in interest rates.

ZIRP maximizes the duration of the bond market. The result is that seemingly innocuous, boring, or risk-free investments transform into bonds of mass destruction.

Bonds of Mass Destruction

Typically, we talk about bonds in terms of their yield, but the value or price of a bond is impacted by both its yield and its duration.

For example, yields on 40-year U.K gilts rose from 3.25% last week to 4.8% prior to the BoE’s intervention on Wednesday. This is a big move for a government security, but it fails to capture the magnitude of value destruction of a long-duration bond.

Let’s look at the price instead.

This particular bond was issued in October 2020 with a coupon of 0.50%. Allegedly sane, sophisticated investors lent the U.K. government money at a fixed rate of 0.50% for forty years. While this sounds like a boring investment, it is an extraordinarily risky bet on interest rates.

With an initial duration of 36 years, if interest rates rise even a little the value of the bond will take a big hit. If they rise to 4.8% you get rekt.

Prior to the BoE’s intervention, the principal value of that investment fell from $100 at issuance to $29 - a 71% drawdown in under two years. That performance is as disastrous as the most speculative equities or crypto over the same period. The only difference is that it came in the wrapper of a low-risk security. Instead of being owned by risk-seeking retail traders, it was bought by institutional fiduciaries4.

Why on earth would a sophisticated investor lend with such an asymmetric risk and reward profile? If held to maturity, you will earn a paltry 0.50% return for forty years5. If rates rise, you see the losses of an alt-coin. Even if these losses remain unrealized, it will still decrease the mark-to-market value of the portfolio, which can prompt margin calls and other ills when paired with leverage and derivatives6. The only possible rationale for buying this instrument is the expectation that central banks would continue bidding bonds higher into negative yielding territory - yet another financial perversion of modern monetary policy.

The most equitable outcome is for investors to bear the losses of their poor investment decisions. Just as the gains of easy monetary policy accrued to private investors, the losses from monetary tightening should also be borne by those private investors. De-coupling risk from reward is the crux of moral hazard.

Yet, in practice this is untenable. Unsurprisingly, there is a far greater political cost to value destruction than there is to the wealth creation of low rates. Further, there is nothing a central banker fears more than financial instability. The solution will always be to intervene to preserve the markets no matter the cost. Socializing losses and privatizing gains while perpetuating long-term instability has been the predictable pattern of central banks.

The Bank of England’s intervention was not driven by increasing yields per se, but rather plummeting bond values, and their impact on systemically and politically important investors, both directly through the ownership of bonds and indirectly through a vast web of fixed income derivatives.

Conclusions

In writing this column, I try to examine topics objectively rather than emotionally. Yet, on this topic it is hard to find a compelling argument that absolves policy makers from the predicament they face today.

Back in March, I posed the simple question:

What happens if you print $4.7 trillion, force it to find a home at 0% rates, then let rates rise (bonds selloff) in an uncontrolled manner? This is elementary finance, which is why the Fed doesn't understand.

The western monetary policy of the past two years was to suppress interest rates to near zero (or below) while flooding the market with liquidity. Trillions of dollars (or Pounds, in the case of the U.K.) were forced into assets, including long-duration fixed income securities like 40-year 0.5% gilts. Providing their tacit blessing, central banks ensured investors that they weren’t even thinking about thinking about raising rates.

Now, slamming on the breaks in a delayed fight against inflation will ensure massive losses to critically important markets such as G7 government debt, risking financial and political stability in the process. This outcome was not merely predictable but a mathematic certainty that should have been considered by policy makers far before they were forced to intervene in market crises.

Indeed, the risk of duration on financial stability was described in The Case for Higher Rates:

Making matters worse, is duration…

By pushing interest rates to the minimum, the Fed pushes financial asset prices to their maximum. The resulting unwind means massive and potentially disorderly value destruction. Particularly when this occurs in fixed income or treasury markets, which are the bedrock of financial markets, the global financial market becomes deeply unstable.

Today, central banks globally are trying to deflate a bubble without popping it: a controlled demolition. As losses deepen and liquidity dwindles, risks only grow.

As always, thank you for reading. If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, tell a friend! And please, let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

-TLBS

Allow me to digress on a pet argument. Duration does not apply to equities. It has become common to hear people refer to tech stocks as “long-duration equities” to explain why they soared during the pandemic and collapsed with rising rates. I disagree, for several reasons.

Duration is important for fixed income because the income is fixed. With fixed cash flows, the only way that present value changes is due to change in market rates (or default probability).

By contrast, equities have no fixed cash flows, maturity, or meaningful par value. The value of the security depends on the residual claims on a business after debt, which has far more to do with business fundamentals (which may be impacted by the rate cycle), than the discount rate you assume. In other words, the long-term value of a stock is far more dependent on whether that company will exist twenty years from now. Further, while not immediate, equities over the long-term should provide some inflation protection as earnings are largely driven by margins, not nominal dollar amounts.

To me, it is more likely that loose monetary policy encourages speculative investment, whether that be in a growing company with a high valuation or in an asset with no cash flow whatsoever (gold or bitcoin). What is the duration of bitcoin?

For an equity investor facing higher rates, the better questions to ask is how will rising rates impact a given company’s financials? Are they levered? When must they refinance? Can they push prices in line with inflation? What are their margins?

Ok, I don’t think this analogy is technically correct from a physics perspective. In physics, the leverage of weights further away from the fulcrum should carry additional force that aren’t considered here, but I still find the metaphor intuitive and helpful.

There are two reasons for this increase in duration. First, a bond with higher coupon will generate much more cash flow in the form interest payments than a lower coupon bond. A 10% coupon bond will pay $400 dollars in interest payments that are received ratably over a 40 year period, whereas a 1% coupon bond will only pay $40 dollars in interest. The cash flow of the lower interest bond is much more weighted to the repayment at maturity. Second, the value of longer dated cash flows is worth less in present value terms in a higher interest rate regime.

While it has been widely reported that U.K. pension funds were at the heart of this week’s crisis, their precise exposure and portfolio construction remains speculative. Many have reported that pension exposure was synthetic through interest rate derivatives, forcing margin calls and liquidations.

Maybe the answer is that long-dated investors like pension funds have to buy long-dated investments. But even in this case, the asymmetry of risk and reward in this investment is so great that it seems impossible to justify even if the purpose is to “match duration” between assets and liabilities. Is any gilt owner, regardless of their liability profile, happy with their investment today?

But wait, aren’t these sophisticated investors hedging their investments? We can’t just look at naked returns of the bonds. Sure, but hedging merely transfers risk between participants. If the original buyer sold its interest rate risk, they it not experience this drawdown, but its hedge counterparty must. Risk can be packaged and traded through the financial system but it doesn’t disappear.

Thanks for the healty dose of reality, sometimes I feel like I'm living in a simulation, with so many people just not realizing what's going on, and maybe thinking (hoping) we will just go back to printing more money soon...

Enjoyed the re-read,thanks for reposting.

What is/will be the net difference between deflating and popping the balloon?

Isn’t it just the same but without the bang??