Higher for (a little bit) Longer

#72: As soft-landing optimism pushes yields to cycle-highs, the landing becomes harder to stick.

There is something disingenuous about this hiking cycle. By traditional measures it has been one of the fastest on record. The Federal Funds rate has increased by 5.25% in just 18 months.

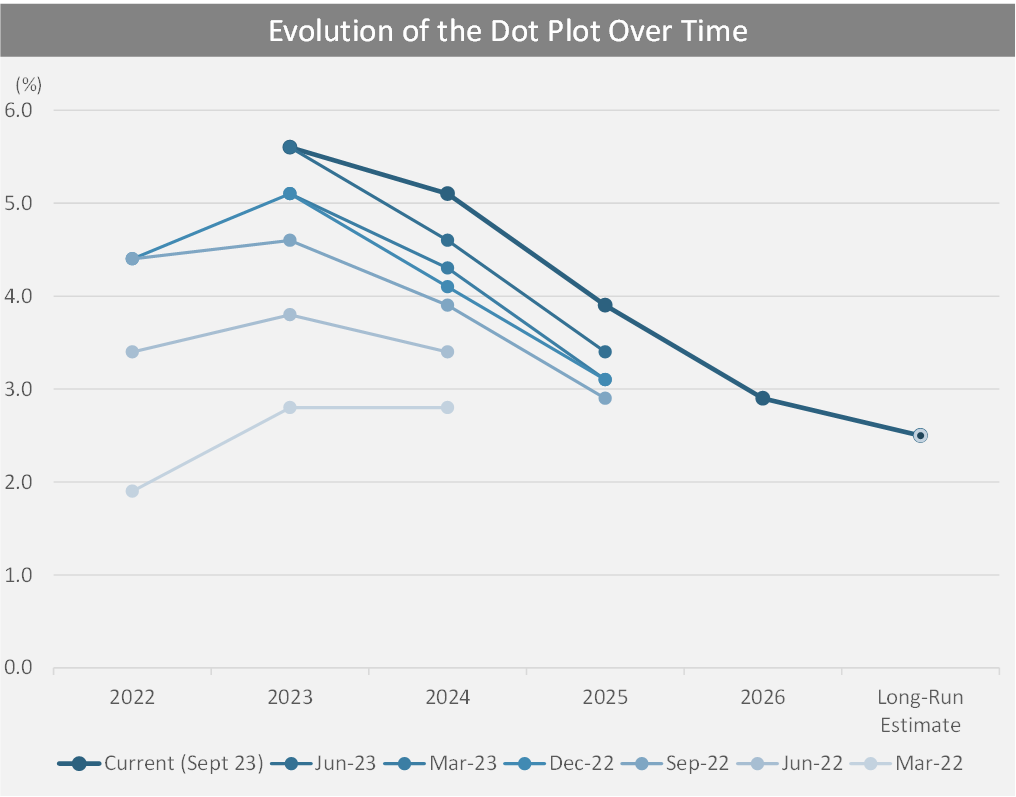

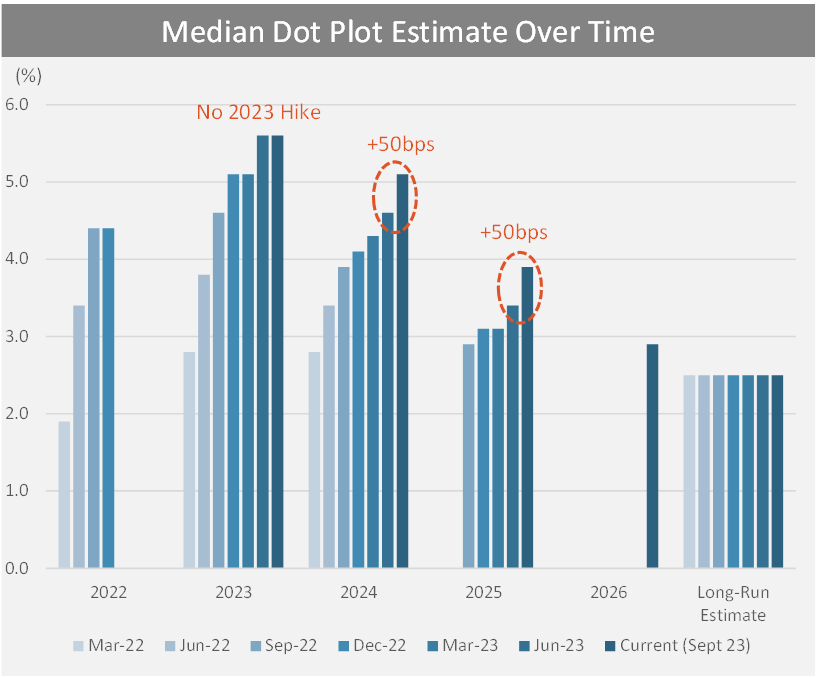

Yet, as outlined previously, the Fed does not merely act through setting overnight rates. Since 2012, it has provided explicit forward guidance through its dot plots. Four times a year, the Fed provides its Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) which outlines the committee's expectation for growth, inflation, employment, and interest rates for the next several years (plus a long-run estimate).

Even as the Fed has aggressively pushed overnight rates higher, it has not adjusted its long-run estimate of 2.5% since 2020.

Perhaps this truly represents the central bank’s best guess of long-run equilibrium rates, but there are reasons to be skeptical. It seems odd that the front end of the curve has required such a historic lift while the long-end should remain unchanged.

It seems more likely that the static long-run estimate is merely a policy decision driven by several factors, notably:

Credibility: A 2.5% nominal rate with a 2.0% inflation target implies a 0.5% real equilibrium rate. An increase in the long-run estimate could be a tacit admission that inflation may remain above the 2.0% target and damage the Fed’s credibility and perceived determination1.

Duration Risk: Because the value of long-term assets is much more sensitive to changes in interest rates, changes in long-term interest rates are scarier. The Fed would prefer to tackle inflation at the front end.

Regardless of the rationale, the practical implications are clear. The Federal Reserve has never truly endorsed higher-for-longer.

The Fed plays good-cop / bad-cop. Short-term hikes scream shock and awe, but at the same time the Fed whispers in the market’s ear, “this will all be over soon”. Despite its near-term dispersion, the Fed’s dots quickly converge, gliding to the same 2.5% long-run estimate.

The market listens. By design, the short-term hikes over the past year have not translated to long-term interest rates, even as the curve has inverted to extreme degrees. Even as the Federal Funds rate has increased by 200bps between 3Q22 and 2Q23, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield rose just 1bp.

This policy significantly softens the blow of rate hikes. Borrowers can lock in debt at advantageous long-term fixed rates (also reducing the effectiveness of future policy hikes). Further, borrowers will avoid any refinancing, waiting for the rate cuts that are literally in the dots.

But even as the Fed refuses to budge from its 2.5% long-run estimate, it has been forced to push up its dot plot for the next several years, sending long-term interest rates higher. While driven by soft-landing optimism, rising rates make it harder to stick the landing.

Higher for (a little bit) Longer

This week’s FOMC was supposed to be a snoozer. No one expected the Federal Reserve to hike, and it didn’t. It also did not change its year-end 2023 estimate, implying one more 25bps hike later this year.

But the Fed surprised in its dot plot estimates, removing two rate cuts from its projections for 2024, effectively raising its 2024 and 2025 rate guidance by 50bps. Even the dispersion of its long-run estimate edged higher, though the median remained at 2.5%. As shown below, this was the largest increase in 2024/2025 guidance in over a year.

While the terminal rate remains unchanged, the Fed believes - or wants the market to believe - that rates will stay higher for at least a little bit longer.

The rationale for the increase within the SEP seems to be in stronger GDP growth projections which were upgraded from the Fed’s previous estimates (inflation and unemployment meanwhile were little changed). Perhaps the increase reflects the Fed’s concern that an outright pause with no hawkish adjustment to the projections would be gleefully embraced by a buoyant market that is counting the days until rate cuts. Or, perhaps it is because the Fed is indeed gradually shifting its opinion on the neutral rate in a post-COVID economy.

Regardless of the reasoning, the message has been received.

Yields across the curve had already been ticking up in recent months as financial stability concerns have eased and economic resilience has remained durable. Nevertheless, this week’s adjustment in guidance has put incremental pressure on the long-end of the curve. Today, the entire U.S. Treasury yield curve sits at cycle highs.