Bridge to Nowhere

#80: Is Arbor Realty Trust going to zero?

Happy Thanksgiving! I hope many of you are enjoying a holiday weekend and are moving a bit slow this morning. In the spirit of the season, I must take a minute to say thank you, yes you, for reading. Without your support, this column would not exist.

Now on to it.

Despite the negative headlines, I have remained relatively relaxed about the state of commercial real estate, at least as a major credit risk within the banking sector. But one corner of the market where I’m more skeptical is mortgage REITs (mREITs).

Mortgage REITS are publicly traded, highly levered pools of loans. They finance new mortgages by borrowing at cheaper rates at the portfolio level, seeking to enhance returns by stacking debt on debt. Because of their credit concentration and leverage profiles, mREITs stand out as a potential risk if things get hairy.

So my interest was piqued when a group called Viceroy Research released a research report titled Arbor Realty: Slumlord Millionaires, which contends that the $2.3 billion common equity of mREIT Arbor Realty Trust (NYSE:ABR) is worthless.

The report can be summarized as follows:

Arbor provides bridge loans to unsophisticated operators to revamp shoddy multifamily apartment complexes

Soaring interest rates have destroyed the economics of these projects. Borrowers are now underwater and cannot refinance these bridge loans

Arbor inflates its collateral value using above-market valuations that ignore the current interest rates. At current market rates, the underlying real estate is worth less than the mREIT’s own debt, implying the company’s equity is worthless

The report isn’t perfect, but nevertheless prompted a deeper dive into Arbor’s financials in order to evaluate Viceroy’s claims. Let’s dig in.

Background

Arbor Realty Trust, founded in 2003, is a mortgage lender that focuses on providing short-term, floating-rate bridge loans for the acquisition and rehabilitation of multifamily commercial real estate assets (apartment complexes). While the company has a wider range of products, these multifamily bridge loans today make up 89% of the company’s loan portfolio, and are geographically concentrated in the U.S. sunbelt.

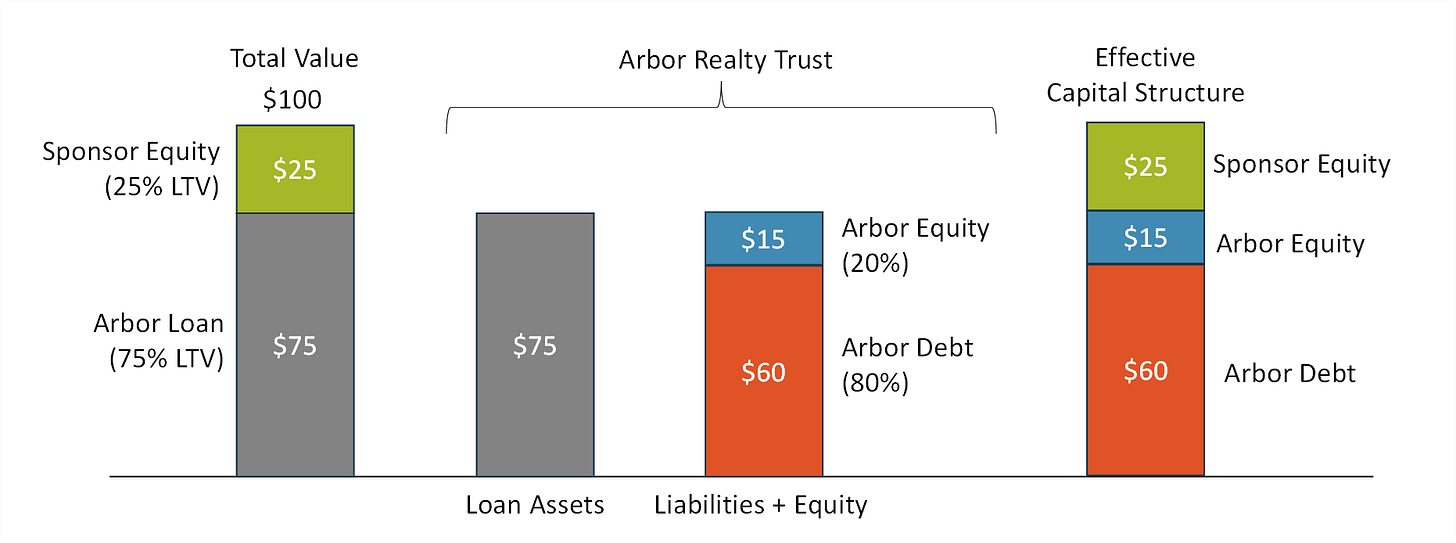

Here’s a simple example of the effective capital structure of a multifamily asset financed by Arbor.

To buy a $100 property, the borrower puts in $25 (25% LTV), and Arbor provides a $75 (75% LTV) bridge loan. Arbor finances this $75 loan with its own equity and by raising debt through a combination of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), credit lines, and unsecured corporate debt. When consolidating these steps, the real estate is effectively owned by the equity sponsor ($25), Arbor common equity ($15), and Arbor debt ($60). The common equity of mREITs like Arbor sits in a mezzanine position, senior to the sponsor’s equity but subordinate to the mREIT’s debt.

If all goes to plan, the new property owner executes on capital improvements, increases the asset’s cash flow and pays down Arbor’s loans with new permanent financing1 — hence a “bridge” loan. If things don’t go to plan, Arbor is secured by the value of the property, which it can sell at a discount of up to 25% (in this example) without experiencing any losses.

Viceroy’s contention is that soaring interest rates and poor business execution has put a majority of these equity sponsors underwater, and the next stage of losses will fall on Arbor equity holders (for which the company has very little provision).

Credit Risks

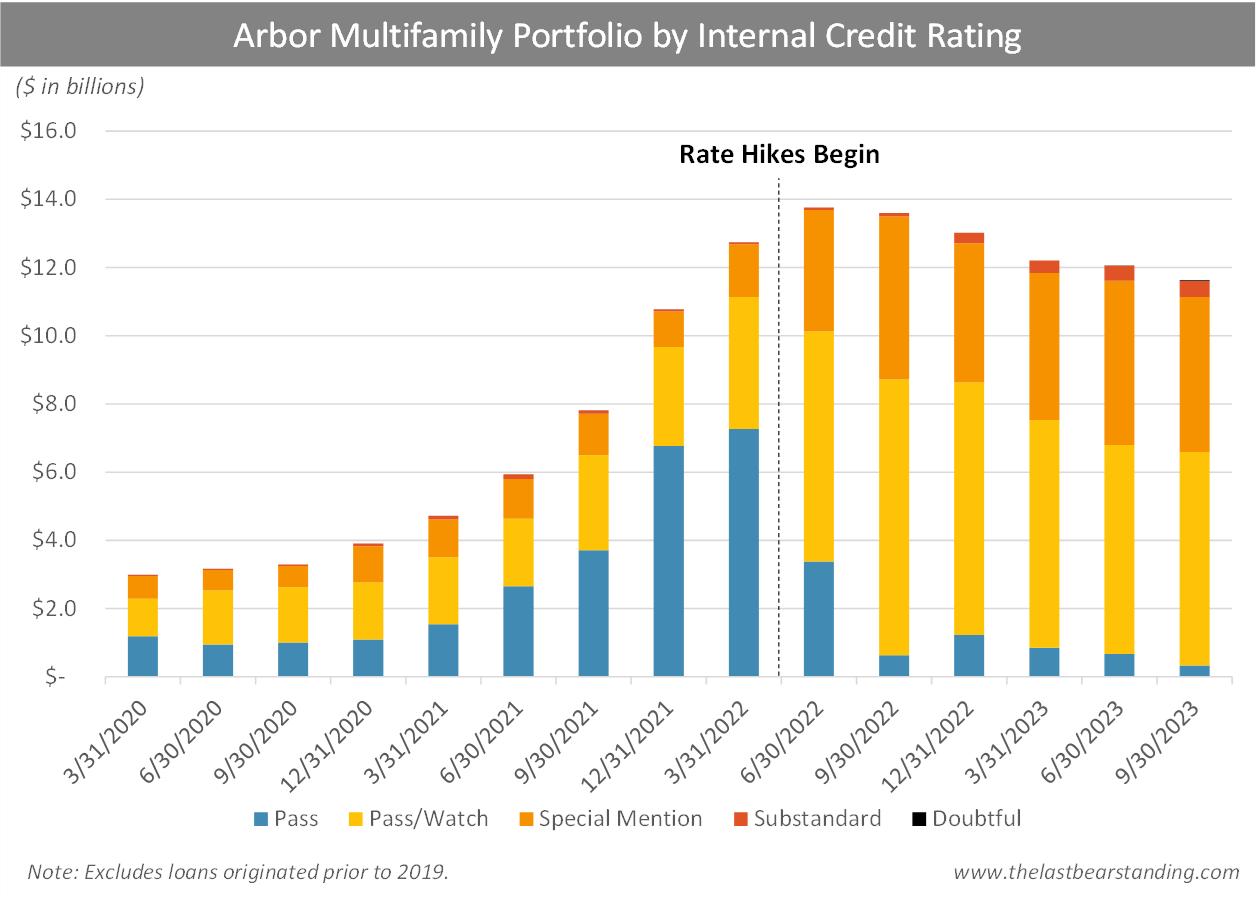

By Arbor’s own admission, its loan quality has substantially deteriorated since rate hikes began in early 2022. Below, I’ve graphed the evolution of the firm’s multifamily portfolio according to its five-scale internal credit rating system (pass, pass/watch, special mention, substandard, doubtful).

Of multifamily loans underwritten since 2019, only 3% of loans today earn the highest grade (“pass”), down from 57% as of March 2022. Over the same time, loans labeled “special mention” or worse have grown from 13% of the portfolio to 43%, now totaling $5.0 billion in unpaid principal.

Management has argued2 that some of the deterioration in credit is a result of the natural aging of the loans. This is both true and a big part of the problem.

Below shows the same credit rating evolution, split by year of origination. It demonstrates that highest quality loans are paid off first (or that loans are downgraded as they remain outstanding).

Of course, this makes sense. After all these are bridge loans. There is a negative survivorship bias at play.

The best projects have already found permanent financing and repaid their loans to Arbor. It’s those projects that haven’t been able to refinance that remain on Arbor’s books. Now those loans are coming due.