Uncle Sam's Tab

#76: Credit growth has shifted from the private to the public sector, but who will foot the bill?

As the United States closed the books on the 2023 fiscal year, the official federal deficit clocked in at $1.7 trillion. Most agree that a more accurate number is $2.0 trillion after adjusting for student debt cancellation accounting, which represents a doubling of last year’s effective deficit.

No matter how you count it, the number was big — the third largest in history behind 2020 and 2021. Relative to economic activity, the gap between income and outlays exceeded 5% of GDP, a level previously experienced only in war or recession. There is little countercyclical Keynesian rationale for a swelling deficit during a period of low unemployment and troubling inflation.

But you have heard all this before. With pundits arguing each angle, the nation’s financial health can feel either existential or inconsequential.

The United States’ slide into structural deficits over the past twenty years seems noteworthy, but don’t you know that a sovereign fiat issuer can’t default? Even if it’s important, it’s not important today. The sun will eventually explode.

But these discussions often ignore the broader dynamics of credit growth across both the public and private sectors. Since 2008, there has been a meaningful shift in the composition of credit away from individuals and financial institutions and towards the Federal government.

Today, government spending has replaced private credit expansion as an engine of growth. This socializing of debt has legitimate economic benefits and has strengthened private balance sheets. Nevertheless, public debt still has a cost, and as those costs compound, we must decide how to foot the bill.

All the Debt

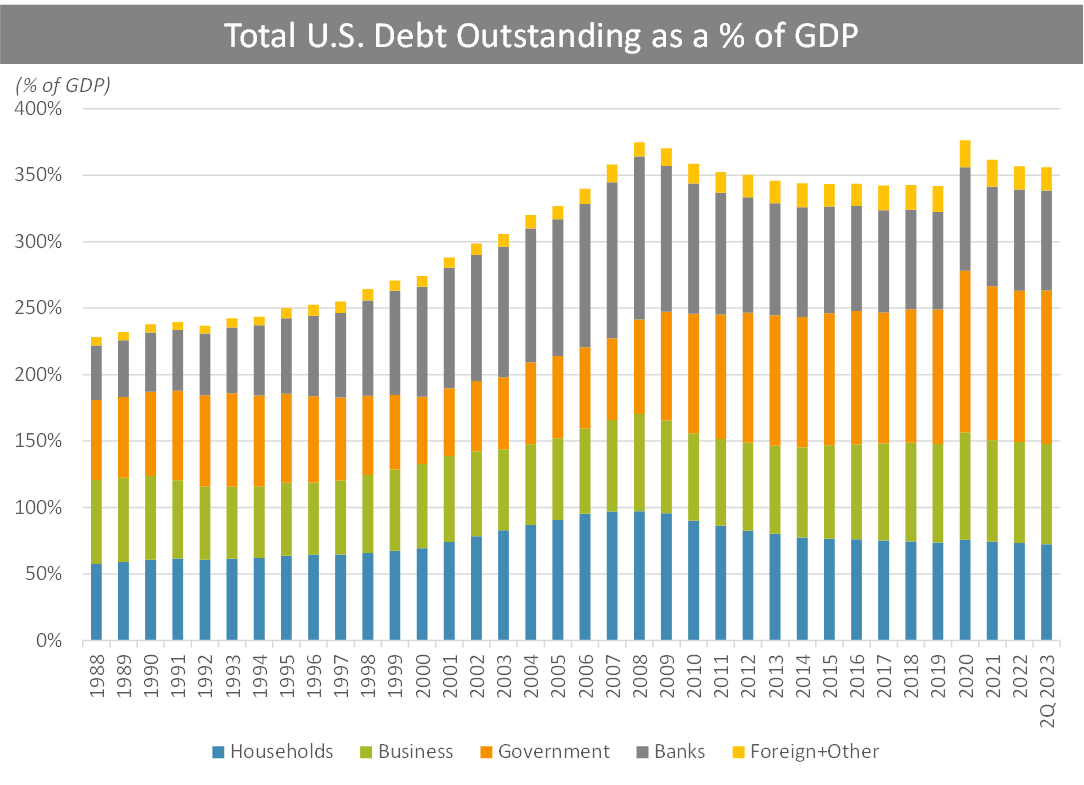

The extension of credit is a key driver of economic growth - it reallocates capital, expands money supply and generates economic activity1. According to the Federal Reserve, there is a total of $96 trillion of debt outstanding across all sectors as of 2Q 2023. Separating borrowers, we can split the debt into four primary categories; households, businesses, banks, and the government.

And while total debts are increasing in nominal terms, aggregate debt outstanding as a percentage of GDP has actually remained relatively constant at ~350% for the past fifteen years.

Yet there has been a significant shift in composition of the borrowers.

Throughout the 1990’s and mid-2000’s credit expansion was driven by the private sector while government debt remained relatively stable. Household debt rose due a surge in mortgage debt. Meanwhile, leverage in the banking sector steadily grew from the mid-1980’s ultimately reaching 33:1 on a cash basis by 2008. (You may know what happened next.)

The popping of the mortgage bubble and financial crisis forced a long period of de-levering in the private sector that has continued through to today. Rather than taking on new loans, consumers were focused on paying back debts. Meanwhile, the near implosion of the banking system due to credit losses and excessive leverage caused regulatory and risk overhauls that reduced bank lending capacity.

But just as credit expansion promotes economic activity and expands the money supply, credit contraction does the opposite. With the U.S. economy careening into the worst recession since the Great Depression, and private sector credit rolling over, the government stepped in to fill the gap.

Deficit spending, which is typical during a recession, helped counterbalance private sector credit contraction. Instead of funding new housing development, new credit would instead fund government spending.

Deficit spending as the primary form of credit expansion didn’t prove to be a temporary measure. Instead, government debt continued to increase as a percent of GDP throughout the 2010’s even as the economy improved. The response to COVID sent federal debts to all-time highs.

Since 2008, total federal, state, and local government debt has nearly doubled from 60% of GDP to 120% today. Now, government debt accounts for 29% of all U.S. debt, up from 12% in 2007, the highest level in the Fed’s data going back to 1988. The flipside of this dynamic was that households have continued to de-lever.

In other words, the country’s aggregate leverage has not changed meaningfully, we just started putting it on Uncle Sam’s tab.

Uncle Sam’s Tab

There are certain benefits to accumulating debt at the public level rather than the private level.

The federal government has the lowest borrowing cost and nearly unlimited access to new debt. The government also has lower credit risk than individuals or businesses. Lower interest payments on the same quantity of debt is a more financially efficient structure. But perhaps the biggest benefit is that it improves private balance sheets.

Take the example of student debt forgiveness. If a borrower has $10,000 of loans cancelled, it will increase that individual’s net worth by $10,000. It increases the person’s purchasing power and financial flexibility and almost certainly provides a near-term boost to consumption. Similarly, a company that receives government support can more easily hire employees, expand operations, and distribute profits to its owners.

But of course the student loan is not truly “cancelled”, rather it is funded by $10,000 of incremental borrowing by the federal government - it is socialized. But who cares?

Today, there is $96,509 of federal debt for each U.S. citizen - up from $70,049 in 2019 or $31,207 in 2008. But no one individually owes that money. No one includes that liability in their calculation of their own net worth. Certainly no one is budgeting to pay that debt down. And given the seemingly endless credit capacity of the federal government, there isn’t a firm limit to how much debt can accrue.

Federal debt is an abstract and amorphous blob with no individual recourse or responsibility. Therein lies its beauty2. So long as Uncle Sam’s tab is open, everyone drinks for free.

Of course, while public sector debt is in some ways less restrictive than private debt, it nevertheless comes with a cost. As we have become increasingly reliant on federal spending as the engine of economic growth, recognizing these costs and choosing our method of repayment becomes ever more important.

Closing Out

How will the U.S. federal debt service be paid? With dollars.

These dollars can either come from taxpayers, lenders, or from the Fed - each has its own set of considerations.

Taxpayers: The most sustainable path would be to reduce the primary deficit via changes in the taxation and spending, though it would require a massive shift from current levels. The Treasury estimates that with immediate action, it would still “require some combination of spending reductions and receipt increases that equals 4.2 percent of GDP on average over the next 75 years.” Such an adjustment would halt the fiscal-fueled economic growth in its tracks, but would ultimately allow lawmakers to decide who in society will pay for the debt.

Lenders: New debt avoids the pain of budgetary concessions today, but ultimately compounds the problem of debt service over the long term and risks exacerbating financing costs for both the federal government and the rest of the economy, absent accommodative policy from the Fed.

Printing: To the extent that the Fed wishes to keep financial conditions looser than the market would otherwise allow, it can monetize some portion of federal debt via quantitative easing, as it has periodically for the past decade3. This currency debasement ultimately pays for debt through the regressive and socially disruptive tax of inflation. While expedient, debt monetization has proven to be a slippery slope with destructive long-term consequences.

The path of least resistance is a combination of borrowing and printing. Below in blue we see the aggregate level of public debt funded through open-market borrowing, along with the amount of debt monetization that has occurred to date in orange (Federal Reserve holdings of government debt).

The relative combination of the three alternatives will be chosen by lawmakers (ultimately voters) and the Federal Reserve4.

But we should consider who in society has benefitted from the policies of deficit spending, and who should bear the costs?

The question is hard to answer. By some measures income and wealth inequality has shrank marginally in recent years (though remains very wide by historical standards).

Yet it is hard to deny that a “K-shaped” recovery from the pandemic is now playing out. While business profits and asset prices remain sky-high (benefitting the rich), the regressive tax of inflation has crushed the initial benefits of fiscal transfers to the lower income cohorts. Deteriorating consumer credit indicates that certain households are under the greatest financial strain in a decade. Meanwhile, dismal consumer sentiment suggests that society at large is discontent with the post-pandemic economy, regardless of the official figures.

I would argue the most progressive alternative is actually budget reform - forcing the balance through the progressive taxation system rather than the regressive tax of inflation. Even still, this alternative would carry negative consequences for employment and economic satisfaction.

Regardless of the path, there will be consequences.

Conclusions

Since 2008, public debt has emerged as a key driver of economic growth. While this shift in credit composition has allowed de-leveraging in the private sector, the increasing strain of federal deficits points to the unsustainability of the present trajectory.

The path ahead requires budgetary restraint (hindering economic growth in the near term), or more likely, compounding debts and gradual monetization. Choosing which path is a critical long-term question for the United States, one that will evolve for decades. The bill eventually will be paid, it’s just a question of how.

Thank you for reading The Last Bear Standing. If you like what you’ve read, hit the like button and share it with a friend. Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

As always, thank you for reading.

-TLBS

Credit growth, even if unhealthy and unsustainable, drives growth in the near term.

Credit extension creates money today for economic value that will be generated in the future. A mortgage borrower receives money today based on the value they expect to create as a wage earner for the next thirty years. A company raises debt today to build a factory that will generate profits in the future.

We give credit today for value created tomorrow. There is no inherent limit on how much credit we can provide, regardless of how prudent our estimates may or may not be. If those estimates turn out to be wrong - if the value does not materialize and loans cannot be repaid - then the lender’s asset is written off. We lose credit for that value.

A debt “bubble” expands based on unrealistic forward estimates, and contracts as those estimates are proven wrong. Further, as lenders recalibrate their expectations or suffer losses, they may be less willing to provide more credit in the future. Credit contraction is a painful economic reality, a claw-back of ill-gotten gains.

At least this is how market-based private credit works in theory.

In private equity (“PE”), there is a popular but controversial maneuver called a “dividend recapitalization”.

In this transaction, a portfolio company of a PE firm raises debt and sends the proceeds to the PE fund as a dividend. The company holds the debt and the owner takes home cash. Theoretically there is nothing wrong with this, the owner is merely monetizing the equity value of the company it owns.

But the key appeal for the PE owner is the utilization of credit capacity and breaking of recourse. You get the dividend today, regardless of whether the company ultimately repays the loan.

Since the U.S. government has enormous borrowing capacity and can transfer cash to individuals with no personal liability for the debt, we have embarked on a national dividend recapitalization. In the process we are “monetizing” our national equity value.

While this certainly appears like an unsustainable model of financial engineering, the unique nature of sovereign debt complicates the calculus.

Though it is worth noting that today, quantitative tightening is “re-basing” currency, by reducing the monetary base, at least marginally.

I would argue the Treasury has little direct control over the outcome as it does not dictate spending, nor has the monetary control of the Federal Reserve.

I think you could make the argument that government deficits are actually larger than what is reported too as the government leverages cash accounting as opposed to accrual accounting when accounting for expenses.

I’d argue that for programs such as social security where I’m paying money into the program today, that this is actually creating an additional liability on the governments balance sheet as I’m now entitled to social security benefits once I hit the retirement age. Granted, the government can cut benefits or increase the retirement age, but effectively I tend to think of this as the government selling me an inflation indexed annuity.

I think the total government deficit is likely larger than reported once you start accounting for these types of liabilities that aren’t necessarily recognized with cash accounting.

It's funny, I just happened to read a note from Neil Howe, an excerpt from his new book, that takes a bigger picture view of essentially these trends. combining the two set of ideas, I expect that political expediency will never result in elected officials choosing to raise taxes as they fear they will not be reelected. as such, the only set of solutions that seem likely are those that include ongoing inflation and potentially some tweaking of expenditures at the margin. alas, I believe it is far more likely that the most likely outcome will be a change in the definition of what a deficit is allowing the politicians to 'show' they have addressed the problem. I also fear that Howe's great conflagration is increasingly likely to occur before the decade ends, and we see a true reset.

thanks for a very good description of the situation.