To Reap and Sow

#4: Cause and Effect in the Modern Economy

“Do not be deceived: God cannot be mocked. A man reaps what he sows.”

Galatians 6:7 (NIV)

My food comes from bags on a shelf, at least as far as I know. My grains and meats probably come from somewhere in the Midwest or Western United States. Maybe my produce comes from California or Mexico. Fiji Water comes from Fiji. But that’s a guess. The truth is, I don’t bother to ask. My food comes from bags on a shelf, and it is always there.

My ignorance is a feature of a modern, advanced economy. Specialization drives efficiency - we each individually focus on one tiny segment of economic need, and if everyone does their job, we all enjoy the collective fruits of abundance. “The Economy” is a team sport.

While specialization leads to efficiency, it also obscures the complex web of connections that make up the modern world - one with cars and houses, concerts and funerals, financial planners and party planners. None of us individually knows how it all works, but we do our part. We are all essential workers - we just aren’t exactly sure why.

Take a small step back in human history, and the connection between work and prosperity is quite clear. In an agrarian society, individuals planted, tended, and harvested the food they and their community ate. There was no ignorance as to how they were fed; they reaped what they sowed.

A modern interpretation of Paul’s letters to the Galatians, quoted above, is one of spiritual karma - if you do bad things, a supernatural force will ensure bad things happen to you. But to a reader of that era, the meaning is far more direct and obvious. If you do not sow seeds, there will be nothing to reap. Merely praying to God will not provide a harvest.

A farmer could choose to live off of last year’s harvest, free from the toils of the field for a season. But the foolishness would be obvious. One does not plant seeds to feed themselves today, but to ensure food for tomorrow.

While the complexity of the modern economy makes it harder to map its connections with precision, the same concept applies. To help understand our present economic conundrum, let us remove the karma - the righteous and ideological blame-games - and focus instead on cause and effect; actions and reactions.

Circulation and the Fiscal Transfusion

If the economy is a human body, then money is the blood. Money circulates.

I manage the finances1 of a small coffee shop, owned by my family. In a given month, we receive roughly $15,000 from 1,500 customers who each pay $10 for delicious lattes and home-baked goods. Every month, we take the money received from our customers and distribute it to five part-time employees, about fifteen different vendors and suppliers, our landlord, the state, and the residual accrues to us as owners.

Over the course of a year, our small operation facilitates hundreds of thousands of dollars in economic activity comprised of thousands of coffee-cup-sized transactions. With each cup sold, we collect a tiny portion of the income earned by our customers in their own professions and convert it to income for our employees and vendors.

When the COVID pandemic hit, government mandates and personal hesitation brought many businesses like ours to a standstill. This was a problem.

Let’s table the question of whether business closures were a wise public health or economic decision, and only consider cause and effect. Existing veins of economic circulation were blocked.

Those most severely impacted were people who derived all of their income from these businesses - employees and owners - but the pain extended beyond them. Vendors, landlords and state coffers were also be hit, perhaps to a lesser extent. The state lost sales tax revenue from bars and restaurants - a meaningful sum, but far from a majority of its total income. Pain was felt by many, but not equally.

These first order impacts cascade into second, third and forth order effects, as employees without income cannot spend money, even at businesses that remained open. While the pain was concentrated in certain areas, total economic activity shrunk substantially. In the second quarter of 2020, temporary unemployment reached 15%, and we witnessed the fastest GDP contraction in U.S. history. This was a big, messy, far-reaching problem.

But the problem was never a lack of money in aggregate - the problem was a lack of circulation. Even though 15% of the workers had temporarily lost employment, the remaining 85% did not. Bartenders and baristas lost all their income, but customers of these establishments saved the money they would have otherwise spent on pints and lattes. This money could have been redirected towards open circulation channels (i.e. buying stuff on Amazon) or saved to buy coffee once the businesses reopened. If everyone had immediately resumed their normal routines and allowed money to flow exactly as it had prior to COVID, the wounds could have largely healed on their own.

Enter, “The Government”, eager to engineer solutions to problems of its own creation. To address a problem of circulation, the government embarked on a massive money transfusion.

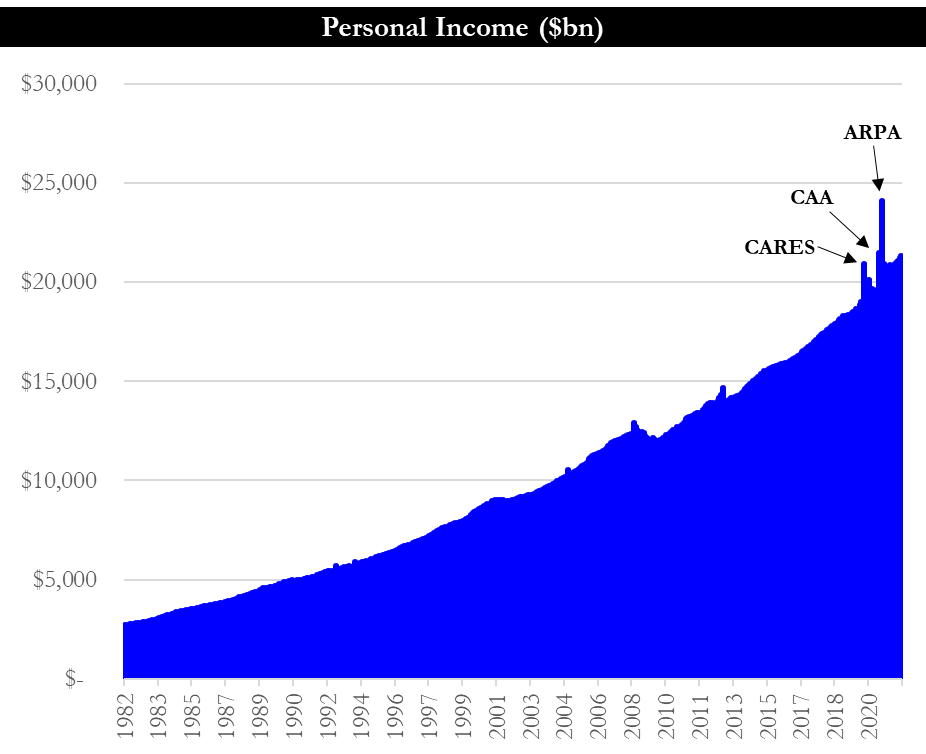

Between the $2.2 trillion CARES Act in March 2020, the $0.9 trillion booster included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act (“CAA”) in December 2020, and the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act (“ARPA”) in March 2021, a total of $5.0 trillion of stimulus was injected into every nook and cranny of the economy, irrespective of need.

The size of this spending cannot be exaggerated and is without historical precedent, outside of war. The total stimulus equaled 23% of pre-COVID GDP, over four times greater than the $830 billion American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009 which represented just 5.5% of GDP, and was enacted to combat a devastated housing market, a global financial crisis and permanent unemployment of 9%.

While enhanced unemployment benefits and paycheck protection programs (“PPP”) were arguably well targeted towards those most impacted by the pandemic, these categories made up a minority of the total spending. A majority of the spending went towards parts of the economy that did not need it, and in some cases had too much money to begin with (i.e. consumers who maintained their income, while also accruing savings due to temporarily reduced consumption).

The great lie of the fiscal stimulus was that it offset income lost due to the pandemic. While this may have been true in certain instances, it is simply untrue in aggregate. In aggregate, incomes soared.

If one were to ascribe a rationale for such excess, a charitable view might be that this was an understandable overreaction to a truly dire economic situation. A less charitable view would be that a good crisis could not be left to waste, and a global pandemic was a perfect justification for wanton deficit spending politicians have always and will always pursue.

But again, this article does not intend to speculate on motives or ascribe blame. The fiscal stimulus happened - what is the effect?

To understand, we must know where the transfusion came from.

The Blood Bank

The exchange of goods and services is not the only way in which money circulates throughout the economy. Money also circulates through capital markets. Capital markets (or simply, the market for money) transfers money from savers to borrowers.

The government utilizes capital markets to fund public goods and redistribute income, particularly in moments of economic stress. In a pandemic, Congress may want to provide enhanced unemployment benefits to workers whose entire industries were shuttered overnight.

Recall, the problem in the economy was never the quantity of money but rather its circulation. Since capital markets are another form of money transmission, this might be an appropriate solution - taking existing blood from where it is backed up and moving it past the blockages.

But since tax revenue does not even cover our ordinary budget, in order for the government to fund discretionary stimulus, it first needs to acquire it from the public by issuing U.S. Treasuries - drawing money from public investors into its own checking account (the “Treasury General Account”). In order to fund the largest stimulus in history, the government would need to draw more dollars from the public then it ever had before.

In capital markets price is determined by supply and demand. Theoretically2, if the government wants to raise trillions in debt to fund spending, it could do so by finding the market clearing price that would induce investors to fork over trillions of dollars. Raising such sums would require a dramatic increase in interest rates, which in turn would drive up the cost of debt for all borrowers, while also soaking up an enormous percent of total dollar liquidity in the public domain.

In defiance of the natural constraints of the capital markets, the Federal Reserve chose instead to dramatically increase the supply of money3 to match the enormous demand.

In less than a month, from March 11, 2020 to April 8, 2020, the Federal Reserve purchased $1.1 trillion in U.S. Treasuries in the open market, creating $1.1 trillion of new money in the process. This was by far the most rapid expansion of the U.S. monetary base in history, dwarfing any intervention in the global financial crisis or early rounds of Quantitative Easing (“QE”). The purpose of this bonanza was to pre-fund the CARES Act, signed on March 27th.

In total the $5.0 trillion of fiscal stimulus was funded largely by the Fed’s direct purchase of $3.4 trillion in U.S. Treasuries, and indirectly from $1.3 trillion in purchases of Mortgage-Backed Securities (freeing up an equal amount of public lending capacity), and further facilitated by the suppression of interest rates to all time lows.

The PPP loans, unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, corporate bailouts, state and local government handouts, were all new money, printed by keystroke at the Fed.

The effect of “one-time” stimulus, when funded by monetary expansion rather than neutral capital market borrowing, is a permanent step-change increase in money supply4.

What happens when money supply increases so dramatically, so fast?

Supply and Demand

We often think of supply and demand as two opposite forces pulling against each other, but in reality they are circular and self-regulating, absent interference.

For an individual, the amount of goods and services you can demand is limited by the compensation you receive from supplying your labor. You spend what you make, you reap what you sow. It’s hard for there to be large, persistent imbalances between the two.

However, if money supply grows dramatically overnight, due to the coordinated actions of U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve, this equilibrium is lost.

Think of money as an economic point system - we all do different specialized tasks and are paid with generic economic points (dollars) that we can exchange for whatever good or service we demand. The great fiscal transfusion gave economic points to all corners of the economy. Funding these points with freshly printed dollars meant they were unearned economic points. It was a lie5 that let us raid the stockpiles.

Consider the logical extreme. If $1,000,000 stimulus checks were sent to every American, could every American buy a Ferrari? No. Because because 330 million Ferraris don’t exist.

The current inventory of Ferraris - last year’s harvest - would be gobbled up until there few were left, at which point, the last remaining ones and any new ones would go to the highest bidder. After depleting the stockpiles, the stabilizing mechanism of price would step in to rectify equilibrium. The illusion of riches would be quickly revealed as such.

For the past two years, we have pretended that we could stay at home, print money, and be rich. Now the stockpiles are gone, and there are no seeds in the ground.

It is tempting to think of “supply chain constraints” as a temporary phenomenon due to COVID restrictions - as if there are goods somewhere that can’t get to where they need to go because of lockdowns. Perhaps in certain instances this is the case, but I argue this is rare. More recently, the war in Europe has been the scape goat - while this has clearly added stress to certain markets, commodity shortages were an obvious and growing problem well before Russia invaded Ukraine.

The problem with supply chains is a lack of supply, due to two years of unearned demand and underinvestment.

Infrastructure is in shortage. Cargo ships were not stalled off the coast of L.A. because the port was shutdown due to COVID - we imported more goods in 2021 than ever in history. There was a shortage of port infrastructure to handle the unearned demand.

Chips are in shortage. New cars are near impossible to buy because of a shortage in semiconductors, yet we are making more chips than ever in history. The auto supply chain is hamstrung by unearned demand for computer chips.

Labor is in shortage. The labor market is tighter than it was before COVID and yet, there are still over a million fewer employees than there were in February 2020, and several million fewer employees than what would be expected based on the pre-COVID trend. The workers were sent home and not all have returned.

Energy is in shortage. Just as seeds are planted well before harvest, the same applies to oil and gas. We stopped driving and flying, and so we stopped drilling for oil. Now, we’d like to fly and drive again but do not have the oil, because we stopped drilling. The federal government has literally raided the oil stockpiles, by releasing a significant portion of the country’s strategic petroleum reserves (SPR).

Food is in shortage. Energy feeds into agriculture via fertilizers and therefore energy shortages lead directly to food shortages. The U.S. is a net food exporter and has the most bidding power of any country, so Americans are unlikely to starve. But in the developing world, people will literally starve, and there will be mass unrest. This has already begun and will only get worse from here.

Last year’s harvest is gone6, and not nearly enough seeds have been sown. After pretending we could ignore the natural constraints of the economy through fiscal and monetary illusions, the market is now slowly killing unearned demand through its natural mechanism - inflation.

The loss of purchasing power is a particularly painful process - like a headwind or quicksand - and it is not experienced evenly across income brackets or countries. Inflation will only subside when the equilibrium is found - the market is wiser than man.

Cause and effect; to reap and sow.

Along with any and every other unforeseen challenge that arise daily.

This point is truly theoretical. In practice, there was no way that Treasury could have issued trillions of dollars of new debt in early 2020 without it being funded by the Fed. The Fed had already been forced to inject liquidity into the system just months prior when the repo market broke in September 2019. At this point, banking reserves clearly were near their minimum, and COVID selloff led to volatility the Treasury market hadn’t seen since 2008. The fiscal stimulus on this scale was only possible because of the Fed.

Of all the positions I’ve taken, the idea that the Fed can print money seems to the most controversial - which to me is odd and fascinating. Rather than argue theories, it’s easier just to look at the data. Take a look at any reasonable measure of money (i.e. M2, monetary base, the Fed’s balance sheet, commercial bank deposits, demand deposits, cash assets at commercial banks) and you see a dramatic, historically unprecedented, concurrent spike in 2020. The data speaks for itself, but Fed Chairman Jerome Powell is explicit as well. Even the 2014 Bank of England paper that is often referenced to make the case that central banks don’t create money is explicit that QE creates money. To quote directly from the opening summary: “The central bank can also affect the amount of money directly through purchasing assets or ‘quantitative easing’”.

To front run any complaint that demand deposits are not the “right” gauge of money supply, feel free to replace this graph with any money aggregate you choose. The story is the same.

It should be noted that the Fed is always increasing money supply faster than the supply of services, which is why prices always go up. In normal course, the Fed likely views this as a “white lie” - one that slips by generally without notice, encourages the expansion of supply and therefore is socially beneficial. However, when scaled to the extremes of the past two years, this white lie becomes much more destructive.

This is not universally true - inventories for certain consumer goods that were over-ordered may remain oversupplied. This is yet another example of resource misallocation driven by our collective choices over the past two years.

Love me a good biblical reckoning. We've been focusing too long on unreal problems, that the real problems have finally shown up.

"Unearned demand." Very well put. Thousands of pages of analysis and a year of debate on inflation-deflation, when this is the elephant in the room to explain persistent, broad-based inflation. Why? Too many vested interests (mostly politicians) had no incentive to admit this monetary/fiscal overdose. And now, the Fed is compounding the error by popping the asset bubbles it created, and potentially pushing demand back down to meet supply at a lower "equilibrium" (if there is such a thing). In the end, will lower levels of supply and demand spark a crisis in private-sector debt servicing capacity? That may be the next question to explore.