The Volatility Squeeze

The next great short squeeze has begun; it will crash the market.

This is not investment advice. This is the opinion of one non-expert on the internet. My opinions are my own.

Anatomy of a Squeeze

What is a “short squeeze”? A short squeeze occurs when asymmetric tails meets forced covering.

Gamestop brought the term “short squeeze” into the headlines when the stock exploded to nearly $350 on January 27, 2021. But the Gamestop squeeze did not occur on January 27 - that is the date the squeeze ended. The actual squeeze looked like this:

Gamestop is a brick-and-mortar game retailer on the losing end of secular trends. GME shares dropped over 94% over the course of six years from 2013 – 2019. At some point shorting GME became “free money”.

The allure of “free money” is bound to draw interest. That’s not immediately a problem, in fact it’s a benefit. As the trade draws more attention, more players will join in, shorting the stock, which drives the price down further which benefits benefiting those already in the trade – everybody who is short wins together.

However, as with all systems that rely on equilibrium, there is a tipping point. At some point, the free money machine goes too far and the risk/reward proposition flips both due to the limited remaining value to harvest, and the crowded nature of the trade.

It wasn’t “apes” or “moonboys” or that launched GME to the stratosphere – rather it was value-minded contrarians that recognized the consensus free-money machine had overshot and was at risk of messy unwind.

The GameStop short squeeze began on August 31st 2020. After trading below $4 in August 2020, the stock saw several bursts of significant buying interest throughout the fall and winter, driving the share price up.

A short seller in September, may not have been too concerned when the stock ran from $4 to $8. A smart investor, who has may have made a lot of money shorting GME, has not changed their opinion on the company – it’s a sinking ship.

But what about when the stock breaks $10 in September? What about $15 in October, or $20 in December?

These months are where the actual short squeeze occurred. If new buyers force a short to close their position, it merely adds more upward pressure on the stock. But, if shorts can overpower the longs, they have succeeded at double down on their short at an incredibly attractive price. It’s a war of attrition

However, what appears symmetrical at the midpoint of the battle, is anything but at the tail end of the distributions.

Shorting a stock at $10 means that your maximum profit if the stock is $10 if the stock goes to zero1. But if you short a stock and it goes up there is no cap on how much you can lose. If the stock trades goes to $20, you will lose $10 – if it runs to $30, you will lose $20 and so forth. This is problematic because you may not have $20 to lose. Since a shorted stock is inherently levered since it is borrowed, forced selling is the eventual outcome. This asymmetry is why you can’t squeeze longs.

Forced covering makes a stock go up. Forced covering in a crowded short sends a stock to the moon. A short squeeze is the meeting of asymmetric tails and forced covering.

Gamestop demonstrates several points:

Shorting GME was a smart and profitable trade for years, which attracted attention in a long term self-reinforcing cycle

A crowded trade reached a tipping point where the risk/reward flipped

The squeeze began in August 31st and ended on January 27th.

Contrarians who recognized the squeeze ultimately made a fortune while short sellers were wiped out

With this background– what if I told you the next short squeeze had already begun, and that would its impact on markets will dwarf that of Gamestop?

The next short squeeze will not be in a stock – but rather a financial “product” that is much, much more important. Volatility.

The Volatility Complex

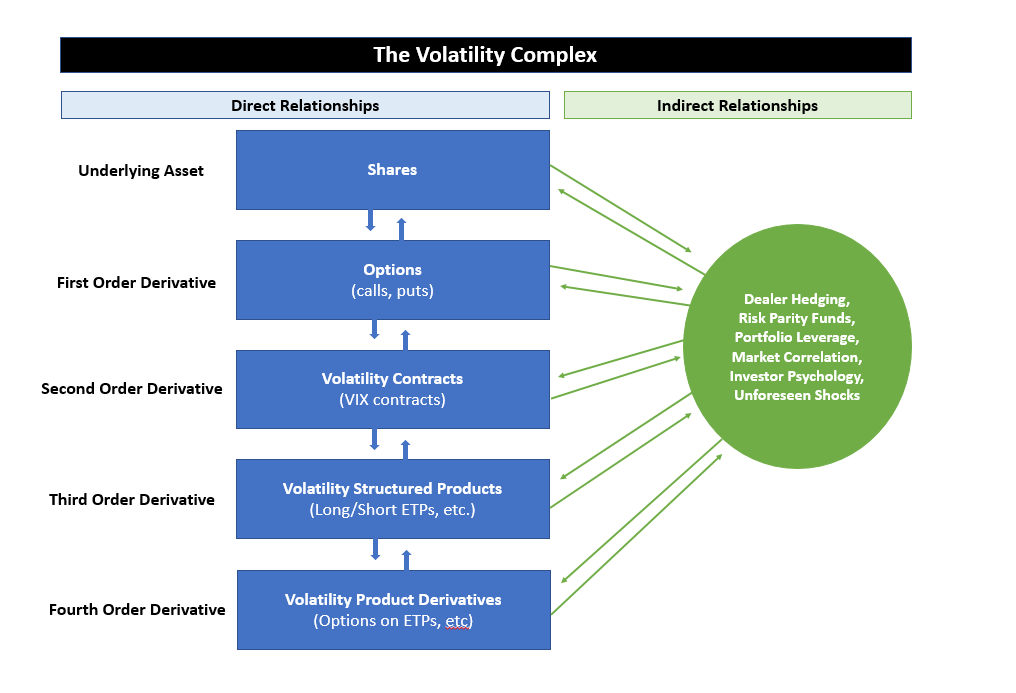

Volatility sounds like a measurement, but this is no longer the case. Volatility is traded product, complete with its own second and third order derivatives. More importantly – it influences the price of every financial asset – in fact, I would argue it is the most consequential product in the market.

A CALL option is the right to purchase a share at a given price at a given point in the future. At its core, an option is forward purchase agreement - this is very easy to value; multiply price times quantity and adjust it for time value of money. But since an option is a “right” rather than the “obligation”, it becomes much harder to value. You must make an assumption about the potential range of movement of the stock to assess the probability that the option will be “in the money” – in other words you must make an assumption on the stocks volatility. It is often said that if you are trading options, you are not trading stock prices, you are trading volatility.

Since option pricing can be broken down mathematically, you can look at the current prices of options and infer the volatility that the market expects – this is called Implied Volatility, because is implied from the current market pricing of options. This Implied Volatility can be quantified into indexes, such as the VIX, which measures the Implied Volatility of the S&P 500.

Implied Volatility does not represent the risk in the market - it represents the market price of risk.

This quantification of volatility went from being a source of information about the market pricing of risk to being a product in and of itself. The rationale for such a product makes sense. If your business is trading options, and trading options is trading volatility, then having a tradeable product that tracks Implied Volatility can be valuable for hedging your exposures. But as is the case with most derivatives, a risk mitigation tool is just as easily a tool for levered speculation. If one wants direct long volatility exposure, you can buy VIX futures contracts and never even have to worry about buying options, let alone shares.

It does not stop there – there are structured products of VIX futures contracts, and derivatives on those products. One can buy exchange traded products or notes (“ETP”s or “ETN”s) that provide long or short volatility exposure through buying VIX contracts, some of which employ leverage. Further, you can even buy options on these ETPs, or even contracts on the volatility of volatility itself (i.e. the VVIX). Movements in each of these products will have direct impacts up and down the derivative chain, sometimes magnifying and sometimes surprising ways.

These products also interact indirectly through the reliability consistent actions of market participants who have exposure at each level. For example, an options dealer will buy or sell equities in order to hedge their options position. A “risk parity” fund will scale its equity exposure based on measures of volatility. Even a retail trader who sold strangles into spiking liquidity, may have their broker liquidates their other holdings to cover their exposure2.

Together they make up the Volatility Complex.

This diagram is a simplification. In reality, this same structure is repeated over and over again in single name stocks, larger ETFs, and indexes, all interacting with each under and the underlying shares in complex ways under the surface, and yet all bound by certain unifying forces. Each incremental derivative level creates incremental potential exposure and complexity, while also magnifying the potential short exposure if things go wrong.

The ever-growing chain the volatility products, its increasing size relative to underlying assets, and the challenge of isolating the indirect relationships means no one has an accurate model of how all these pieces fit together and outcomes when everything is considered.

Volatility is Easily Squeezed

Volatility is a traded product, whose price is determined by buyers and sellers. You can bet for (long) or against (short) volatility in the same way that you can buy or sell a stock. But similar to Gamestop, there are asymmetric tails. Short volatility has a very long tail of downside.

A PUT option is insurance. Buying a PUT gives you the right to sell a stock at a certain price in the future, guaranteeing a floor price for which you can sell if the market was to drop. The most money a PUT buyer can lose is a 100% of their premium. The insurer is on the hook for however much the stock drops below the strike – which could be multiples larger than the premium they received by selling the insurance. The potential exposure a trader takes by selling this insurance is multiples higher than the actual money they receive in the trade.

The volatility complex is much more expansive and interconnected than a single index, but for simplicity consider the most common volatility measure – the VIX.

If you are short the VIX, and the volatility spikes you will quickly see meaningful losses, and you may choose or be forced to cover. This may be done through simply selling the product or buying volatility as an offset, but the net result is that a former seller of volatility is forced to buy volatility, which of course adds to upward pressure on the price of volatility.

This is not theoretical – maybe the best example of a short squeeze prior to Gamestop occurred on February 5, 2018, known in hindsight as “Volmageddon”.

On February 5, the VIX spike from 17 to 37 in a single day – below is a graph of the VIX in the days leading up to February 5th. There was no external catalyst or market event that seemed to justify the massive increase in volatility.

To help explain what happened on that day, this post-mortem of Volmageddon published by the CFA Institute, is revealing.

Excerpting from the summary of findings (emphasis mine):

“A sudden rise in market volatility on 5 February 2018 led to a one-day loss of more than 90% in the value of short volatility exchange-traded products (ETPs).

Both ETPs (XIV and SVXY) were designed to provide investors with a return that mirrors the inverse performance of the S&P 500 VIX Short-Term Futures Index [shorting volatility].

When volatility spiked in February 2018, there was a sharp fall in the value of short volatility ETPs and an increase in the notional exposure of their short VIX futures positions. To remain market neutral, the ETPs needed to buy a large number of VIX futures contracts.

The purchase of VIX futures had a significant positive price impact on futures prices and led to further drops in the AUM of SVXY and XIV. This necessitated further rebalancing and, therefore, even more shrinkage of AUM.

The large market share in VIX futures contracts held by leveraged ETPs exacerbated the volatility shock, sending the ETPs’ rebalancing mechanisms into overdrive. This negative feedback loop kept pushing futures prices upward, leading to huge downward pressure on the ETPs’ AUM and, eventually, to investor losses of around 90%.”

In simpler terms, volatility was squeezed. Specifically, a structured volatility product was squeezed. The mathematical covering process employed by the structured product created a feedback loop that lead to capitulation and near total wipeout.

But as with Gamestop, the roots of Volmageddon far precede February 5th 2018. Up until early 2018, the VIX had been on a consistent decline since mid 2016

For years, shorting the VIX was a great trade – in fact it had become “free money”. From 2016 through early 2018, the product quintupled. Every small volatility spike that temporarily dented performance was quickly overcome as the VIX continued to drift lower over. As with all “free money” trades, it became crowded, and the ETPs became a bigger and bigger player in the market.

Further, while the focus is on the ultimate capitulation occurred on February 5, the short squeeze began well before. The VIX reached a recent low of >9 on January 4 – a month prior to the Volmageddon. From January 4 to February 2, the VIX nearly doubled from 9 to 17, putting significant pressure on volatility sellers.

The explosion on February 5 was merely when a popular short volatility product broke.

A shrewd trader may have noticed the VIX rising in early January and closed their short volatility position or bought volatility in advance. A shrewder trader may have had much further warning much in advance, noting that the volatility (VIX - blue line below) and the volatility of volatility (“VVIX” - orange line below) had significantly decoupled from their historical correlation, implying that the market could be under pricing volatility. From April 2017 to February 2018, the VIX continued to decline while the VVIX had steadily increased. Ultimately the two converged on Volmageddon.

The Volmageddon follows the same architecture as Gamestop:

Shorting volatility was profitable for years, attracting attention in a long term self-reinforcing cycle

A crowded trade reached a tipping point in which the risk reward flipped

The short squeeze occurred from January 4th to February 2nd and ended in capitulation on February 5th

Contrarians who recognized the squeeze in real time made great returns, while short volatility sellers were wiped out

A short squeeze is the meeting of asymmetric tails and forced covering

Importantly, there was not an obvious catalyst for the market movement – rather it due solely due the forced covering of a derivative product.

The Current Landscape:

Now, let us evaluate the present. Volatility, as measured by the VIX has in general declined since from March 17, 2020.

After the extraordinary realized volatility from February to March 2020, attributed to a panic over the COVID pandemic, the market price of volatility was incredibly elevated. Meanwhile, realized volatility since has only compressed – insurance has never paid out.

Below is the realized S&P volatility going back to 2015 (via @spotgamma as of 9/21/21 - with my drawings added). The collapse of realized volatility since March is clear, but also mirrors the past three volatility cycles.

(h/t @spotgamma)

The compression of realized volatility has compressed the markets pricing of volatility. This seems intuitive, but in actuality is the gambler’s fallacy. Recent history does not necessarily dictate the future, and a longer historical look shows that periods of high realized volatility do occur, often occur quiet abruptly and after a long period of declining realized volatility.

Looking at the correlation between the VIX (blue) and VVIX (orange) which was an early forewarning for Volmageddon, we notice more ominous signs.

After remaining relatively well coupled from over a year from March 2020 to April 2021, the VVIX reached a post-COVID low on April 9th and has risen meaningfully. Meanwhile the VIX continued to decline throughout the late summer until reaching a low point in early July. This VIX/VVIX divergence over the past several months and quick convergence that we are seeing today corresponds with the action prior to the two most recent volatility squeezes – the September 2018 selloff, and the March 2020 COVID crash.

While this divergence is a longer-term risk indicator, it doesn’t mean a reversion is imminent. But more recent action in the VIX provide a more imminent warning.

After driving to new lows nearly every month since the March 2020 crash, the VIX reached a distinct local bottom in early July - three months ago. The VIX has risen over 50% since. The important factor for the squeeze dynamics is its change off the lows.

With each movement higher, there is more pressure on volatility sellers. Like Gamestop from $4 to $20, losses can be withstood for a period of time but not indefinitely. At some point, someone goes upside down and is forced to sell. At some point someone really big goes upside down. A short squeeze is the meeting of asymmetric tails and forced covering.

Yes, the VIX has increased for extended periods since the COVID crash (September 2020, or leading into January 2021), but there are several key differences:

First, the lower the VIX falls and the more crowded the trade becomes, the more likely a squeeze becomes

Second, looking back to the VIX/VIXX chart, the VIX looked appropriately priced relative to the VVIX prior to April 2021, implying that the market was not meaningfully under-pricing volatility during those periods

Third, shorting volatility has become a more and more crowded becoming popular with professional and retail traders alike

Finally, the economic outlook by all measures would have been seen as improving during those periods. Today, the opposite is true. Growth has peaked, fiscal and monetary measures have ended, dollar liquidity is fading, inflation is a real concern, corporate margins are under pressure, a burgeoning energy crisis is underway, and a potential US default still not technically out of the cards.

This rise in volatility has also come with a meaningful increase in realized volatility, with equities selling off significantly. The >2% decline in the S&P on September 28th was the largest move since May. As of writing, the S&P 500 and SPY ETF don’t have a positive gamma strike at or below the current traded levels - let that sink in.

The squeeze will play out over time before its final capitulation. The capitulation may be triggered by period of high realized volatility (perhaps due to an unforeseen event) which may put specific volatility sellers out of the money forcing them to quickly cover.

Alternatively, a slower shift in the balance of volatility supply could cause a more gradual repricing of volatility that applies slow but increasing upward pressure on volatility. This could be active through investors seeking hedge protection (buying puts as an example), passive as options positions expire, or some other feedback loop such as spot prices drifting further from open calls and closer to open puts (a key feedback loop detailed here).

Given the intertwined volatility derivative universe, we can’t predict exactly where in the Volatility Complex this would arise, but a breakdown at any level of the derivative chain could lead to chaos elsewhere. There are enormous potential exposures.

It’s certainly possible that short sellers will remain in control of the market for the coming weeks or months, but until the VIX takes out its July lows the battle is on.

Okay but maybe you are a conservative trader with unlevered long positions in blue chip stocks – do you need to care? Yes.

The Devil’s Correlation

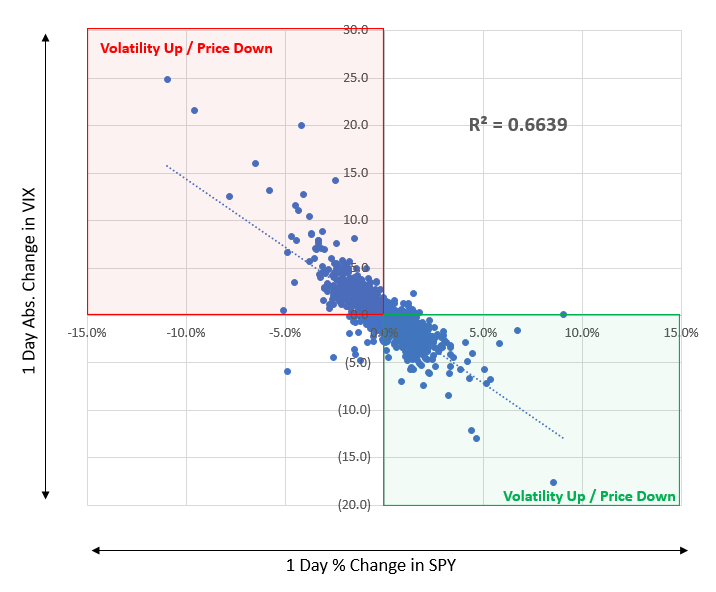

Volatility is negatively correlated with price. If volatility is squeezed, the market will go down fast. If you believe it is possible for the VIX to spike, you believe it’s possible for the market to crash. This is the single most important correlation in the current market structure and yet is rarely discussed. Of greater importance, this correlation increases substantially with more extreme movements in price3.

The Devils Correlation means that owning equities is effectively shorting volatility. Similarly, shorting volatility is merely a highly levered bet that the market will not go down. This has enormous implications for anyone in the market regardless whether you are directly participating in volatility products or not.

To demonstrate - Below is VIX (inverted left axis) and the S&P 500 (left hand axis) from September 16th to the 24th. This is not cherry picking a particularly correlated week – you can repeat this exercise on any day of your choosing and find a similar correlation.

This correlation is demonstrated over much longer periods. Below is a scatter plot showing the the daily percent change in the S&P 500 and the absolute change in VIX over the past 10 years. The R-squared for a linear regression across the 10-year dataset is 66.4%, implying a strong correlation, which is visually obvious.

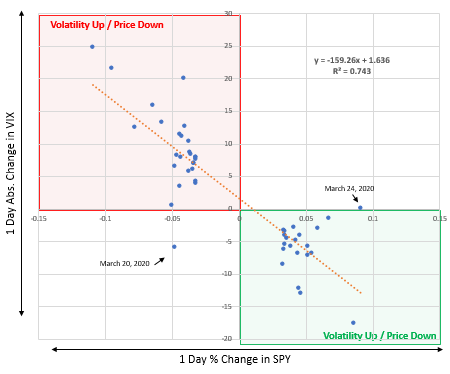

The correlation increases greatly with more extreme movements. Splitting the data set by standard deviation (“SD”) moves in S&P pricing:

<1 Standard deviation: R-squared = 43%

1 – 3 Standard deviation: R-squared = 72%

>3 Standard Deviation: R-squared = 74% (shown below)

Of the 48 days of >3 Standard Deviation moves in the S&P 500, only two days broke the rule. Those two dates, March 20, 2020 and March 24, 2020 bookend the bottom of the COVID crash. On March 20th, the S&P continued to fall while Volatility declined. This proved to be a key signal the end of the selloff was very near.

We don’t need to be able to prove definitely why the correlation exists – the only thing that matters is its clear existence4. Ultimately to derive a perfect mathematical calculation for the correlation would require a complete, accurate model of the Volatility Complex that simply does not and will not exist. We can point to any number of specifically factors that play a roll (risk parity positioning, dealer hedging, etc.) but ultimately building a bottoms-up model is impossible, and not needed since the top-down correlation indisputable.

To make the point in direct terms:

If volatility spikes the market as a whole will experience a significant draw down. I’m not telling you this to get clicks or subscribers – I’m telling you because its what I believe to be true.

The reason for these highs is largely due to the sell-reinforcing cycle of shorting volatility.

As for how draw a selloff could go? The market trough of the three unwinds has each been lower than the last, and that each subsequent cycle has resulted in higher volatility that the previous. In other words, the market is at significantly higher prices than previous episodes and yet is less stable. I worry a squeeze could be very swift and violent for a number of reasons:

Volatility Market Size: The Volatility Complex has by any measure become a more important factor in our current structure. The total notional value of options has eclipsed the actual volume of underlying shares traded. Further, the volatility derivative complex is growing, particular among unsophisticated parties. The tail is wagging the dog.

Asymmetric Options Positioning: Option open interest, a key part of the Volatility Complex, are not evenly distributed. Not only is there significantly higher PUTS open, but they are distributed much further away from the current spot price (i.e. lower). Open CALLS are much closer to current prices. If the market breaks away from the current gravity of the open call options, as it seems to have done over the past week, it will fall increasingly into put-skewed territory.

Crowding in Short Volatility: Shorting volatility has become a more popular trading strategy. More volatility sellers just leads volatility to be under priced, while also creating more dominoes that could be toppled.

Market Leverage: Forced selling is a key amplification of squeezes. While many volatility products have inherent exposure through their asymmetric distributions, the high level of “normal” leverage in the market through margin debt and levered professional funds is at all time highs particularly when compared to available cash in margin accounts.

Neutered Fed: The Fed is much limited than it was in prior volatility spikes. Short rates are at zero (as opposed to 1.75% pre-COVID), and quantitative easing (“QE”) has already saturated the market with liquidity, which is now contracting. Additional bond-buying may prove a counter rising long term rates, but will not add liquidity to the system and will simply end up in the reverse-repo facility

Deteriorating Macro: The macro environment continues to deteriorate, providing any number of exogenous shocks to amplify the correction. Indeed a swift selloff in US equities would have a ripple effect in global financial markets that make an unexpected global event more likely to occur.

To address potential counterpoints:

Dealers are Hedged: Risk models existed prior to every other extreme market event and failed to prevent each. Reality too complex to be modeled with accurately, especially on tail ends of the distribution. Further, these hedging models may have unintended consequences. The hedging mechanics of ETPs are what caused Volmageddon. Similarly, a massive move in in options delta or gamma would cause a dealer to short an enormous amount of S&P futures. This may make “hedge” the dealer, but its consequences from the market are huge nonetheless.

Powell Will Print: The Fed has significantly fewer tools at its disposal than it did in March 2020. They have already lowered rates to the lower bound and maximized credit expansion to the extent humanly possible. All the money printed in the past year that found a home at very low rates could actually prove destructive in a draw down as the value of its investment decline.

No Trigger: Did the market crash in March because of COVID, or was a volatility unwind merely attributed to COVID? If it was indeed COVID that caused the crash, it means the market is highly irrational. The market was making new all-time highs as COVID began to spread in China and elsewhere in the world throughout February. Then, it bottomed in late March before any of the economic fallout globally was visible. Rather, its seems more probable that a large volatility unwind that caused the market to crash in the way that it was which was both attributed to and amplified by COVID. Similarly, when the next volatility unwind occurs, it will be ascribed to a economic catalyst of which there are no shortages (supply chains, rising rates, inflation, declining growth, China, energy crisis, etc.).

Conclusions and Positioning:

Volatility has become the most important force in the market. By quantifying and trading, and speculating on volatility, we add signification risk to the market. Now the market is just two sides of the same trade. Short volatility or Long Volatility. Short volatility has become quiet crowded.

Knowingly or not, the market is now a roulette wheel. Short Volatility is like betting on red and black - likely to win most spins - but the payout each time gets smaller and the tail risks grow. Long Volatility is picking green - unlikely on each spin but unavoidable in the end. The highest rewarding but most painful trade today is paying to bet on green.

As for less experienced traders - particularly ones that have started out since March 2020 - you have already won (almost). You timed the greatest bull run in history to perfection, in the face of the experts (including this Bear) who told you it was a bad idea. But while your account shows a total balance in dollars, you do not have dollars – you own shares of companies, which are being shown at the present exchange rate to dollars. The key to investing is to buy low and sell high.

I won’t comment on how to gain from a volatility spike, but it should be straightforward - either be on the sidelines or on the right side of the squeeze. The more that people begin to position themselves for this possibility, the more likely it is to occur as the market for volatility shifts from sellers to buyers. It is self-fulfilling. Contrarily, if volatility sellers remain strong in the war of attrition it may take longer for the final capitulation. Breaking new lows on the VIX would indicate the squeeze is off for the time being.

Unfortunately there are serious ramifications that go beyond the market. A significant volatility unwind and market draw down real will have real effects on peoples well being, financial stability and the economy. This won’t be caused by a single traders actions, but rather with the widespread market structure that we have built for years. Would it be better if the market was not beholden to a web of volatility derivatives? Yes. But presently, there appears to be little concern over the dangers, let alone any attempts to correct it. Therefore, while the timing is uncertain, the outcome is predetermined. The only thing to do is prepare.

Ignores borrowing cost.

Recent data shows that while small order call-buying has decreased meaningfully since its peak in February, sell to open options have remained elevated. Small sell-to-open data shows retail is selling a similar amount of puts and calls, suggesting to me that they may be simply selling strangles - a highly exposed trade in a downturn.

This is true at the market wide level, however is more varied for individual micro structures. For example, if many out-of-the-money calls are placed on a single stock with little open options interest and low liquidity, the stock may rise as dealers hedge their position by buying the stock leading to an upward prices and upward volatility (a “gamma squeeze”). Even at the market level you can see rising prices coming with rising volatility - but this is often a key leading indicator of a coming reversal in prices, as was seen in the case of (i) Volmageddon (ii) March 2020 COVID crash, (iii) September 2020 unwind. This rising price, rising volatility is also evident in July - August 2021, prior to the market beginning to fall in September. However, as discussed here - large standard deviation movements in price at the macro level are negatively correlated with price as a near rule.

Note that despite this correlation, the VIX continues to stay roughly flat over the long term while the market increases. This is because VIX mathematically is a derivative of price. If you plot the line (2X + 2 = Y) it will show an upward sloping straight line. The first derivative would merely a flat line equal to 2. I’m interested to try to use the concept of “integration” to try to draw a better correspondence between VIX and S&P 500 in the long term, but alas, it must wait.

Thank you for the excellent read, been following your coverage on the Chinese markets for a while now.

Too many people in these comments confuse the quality of a prediction with the accuracy of the expected outcome, it is the analysis behind the justification that proves quality, and you are unmatched.

I like the contrarian thesis that COVID was not the source of the market crash, but volatility. Maybe 10-20% correction should have been expected, but short volatility "fanned the flames" down to the -40% we had.

What would you estimate the combined value of the Volatility market to be? If US equities are ~$50T total MC, how much does the underlying move this "lying"?

Great write-up, Bear