The Nuclear Narrative

#140: Pouring cold water on the market's hottest trend.

A Nuclear Renaissance is Upon Us! Haven’t you heard?

Last year, the mood in the power sector turned giddy. The voracious energy appetite of datacenters has provided the first long-term bullish case for power demand in decades, transforming stagnant industry players into market darlings (see: Datacenters and Power Demand). Zero-carbon baseload nuclear energy suddenly became a key ingredient in technological ambitions.

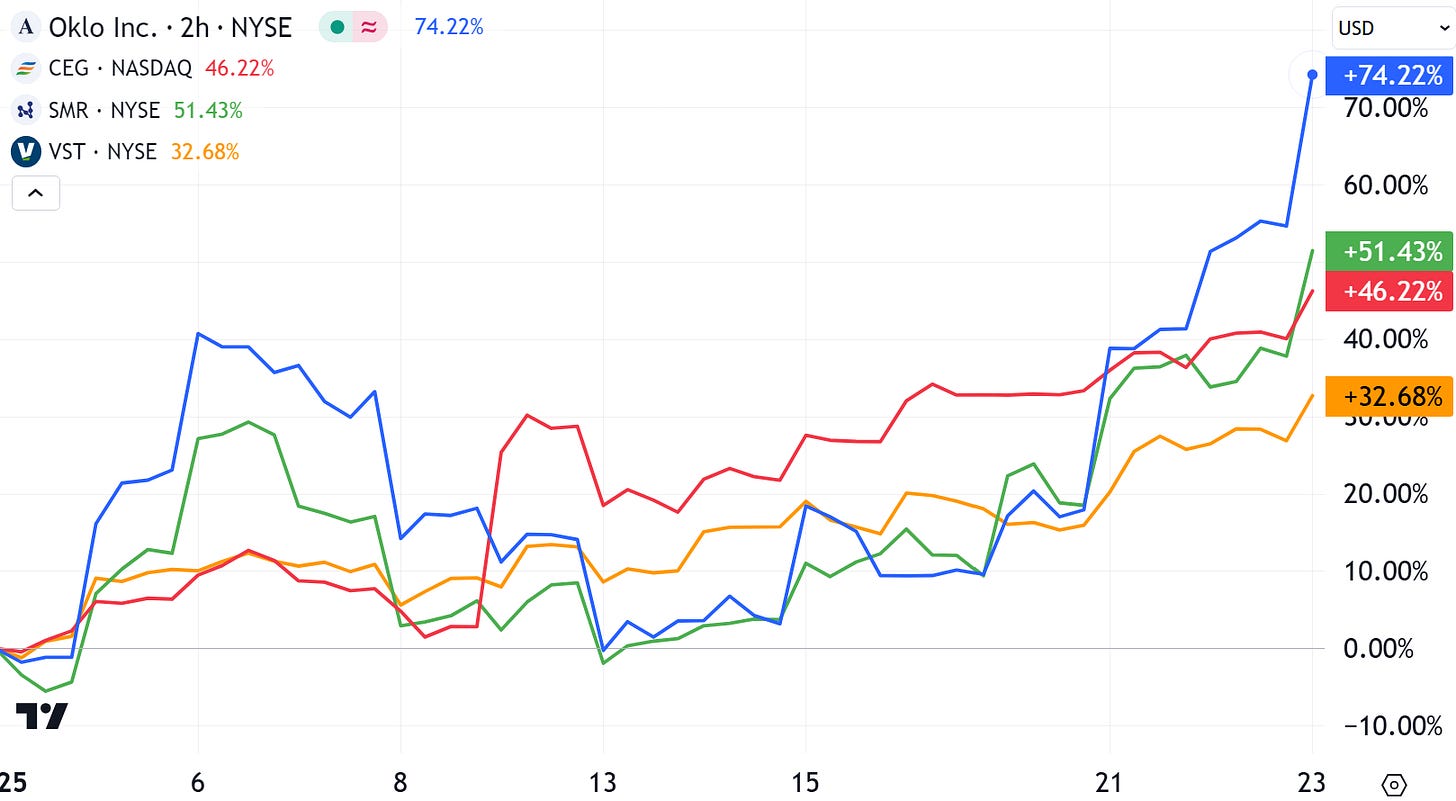

The momentum has continued this year. So far in 2025, nuclear power has dominated the market charts. Four of the eight best performing large-cap1 stocks are nuclear plays — Oklo Inc (OKLO), Constellation Energy (CEG), NuScale (SMR), and Vistra Corp (VST) — which have grown 32% - 75% in market value over the past three weeks.

Of course, there are tangible catalysts supporting the hype. Upsized demand forecasts and ever growing datacenter capex budgets have reshaped grid planning and reliability needs. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has also begun providing new critical subsidies to nuclear plants. And announcements of datacenter co-locations and nuclear plant restarts have put weight behind the claims of a nuclear resurgence:

Palisades Restart: With the support of billions in loans and grants from state and federal agencies, Holtec intends to restart the 800MW Palisades nuclear facility shuttered in 2022 (Sept. 2023)

Susquehanna Datacenter: Amazon purchased a 650MW datacenter co-located on Talen Energy’s (TLN) Susquehanna nuclear plant facility, entering into with a 20-year power purchase agreement (PPA) (March 2024)

Three Mile Island Restart: Microsoft has entered to a new 20-year PPA with Constellation that would support the restart the 835MW Three Mile Island I nuclear facility shuttered in 2019 (October 2024)

Oklo LOIs: Oklo announced 750MW of incremental letters of intent (LOIs) with two unnamed datacenter companies to purchase its prospective small nuclear reactors (November 2024)

V.C. Summer Nuclear Station: Just this week Santee Cooper announced that it intends to market its partially built 2,200MW nuclear station — a project that was abandoned in 2017 due to cost overruns (January 2025)

For an industry accustomed to economic pressure and massive capital overruns, retirements and project abandonments, this flurry of activity is a welcome change of fortune.

But a Nuclear Renaissance? It’s time to dump some cold water on this hot sector.

Hard Truths

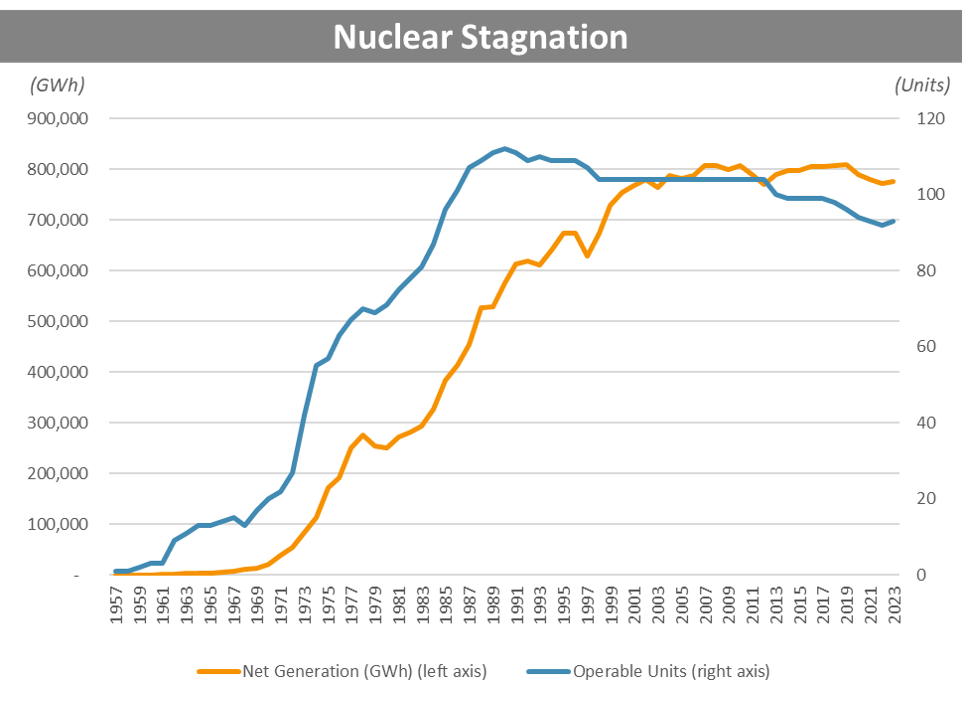

The nuclear power industry in the United States has been stagnant for over thirty years. The number of operable units peaked in 1987 and net generation has been flat since the late 1990s. The average operating U.S. nuclear power plant is 42 years old.

The two most recent new reactors, completed in 2023 and 2024 at Georgia’s Vogtle plant, were not driven by datacenter demands but instead marked the completion of a project than began construction in 2009, delivered fourteen years later at a total cost of over $30 billion for just 2,200MW of generating capacity.

There are currently no new large scale power plants in development in the U.S., and if one were to be announced today, would likely take well over a decade to complete. Simply put, the capital cost of newbuilds is prohibitive.

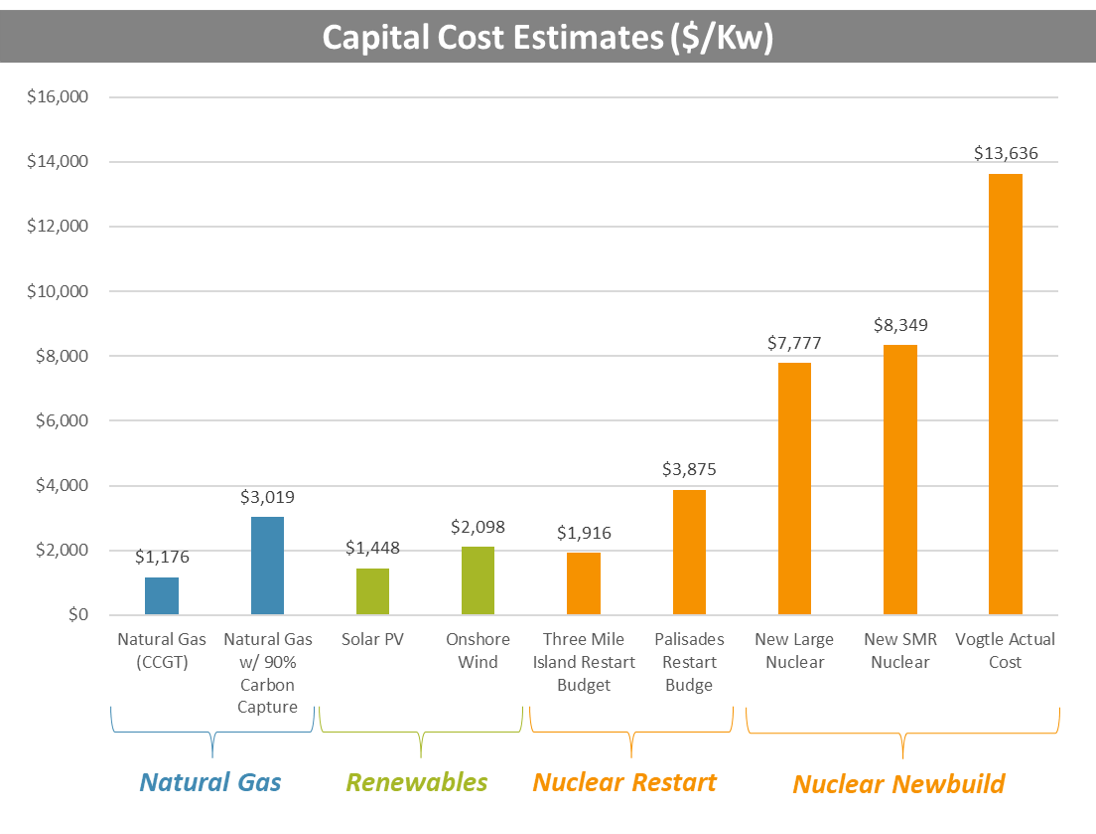

The federal Energy Information Agency’s (EIA) benchmarking shows that newbuild nuclear costs 4-7x that of new natural gas or renewables generation. Even natural gas with 90% carbon capture — which mirrors the low-carbon benefit of nuclear — is estimated to cost less than half of a newbuild nuclear reactor.

The actual experience at Vogtle was far worse than these estimates, and the more recent V.C Summer project was abandoned entirely due to massive cost overruns. While the stated restart budgets for Palisades and Three Mile Island are more competitive, history cautions against trusting these figures and timelines, particularly since these are the first nuclear restart projects ever attempted.

Even if Three Mile Islands and Palisades meet their budgets, the net impact of these restarts is limited. At a combined capacity of 1,635MW, these two projects would add just 1.7% to the total U.S. nuclear generating capacity. And they won’t happen immediately. While Holtec continues to push an aggressive 2025 timeline, Three Mile Island is not slated for completion until 2028.

And there are very few, if any, additional restart candidates. Most retired plants are too far down the decommissioning and disassembly process — the prospect of repairing and restarting long-idled plants presents an even more formidable challenge.

Beyond capital costs, existing nuclear plants struggle to remain profitable against natural gas and renewables. In fact, the greatest boon for the nuclear sector hasn’t been new datacenter demand, but rather direct subsidies through Production Tax Credits (PTCs) granted in the IRA, which cushion profitability as power prices decline below breakeven costs.

The Microsoft/Three Mile Island’s PPA is telling. At $100/MWh, Microsoft will be purchasing power at a ~150% premium to the current wholesale electricity rates of $40/MWh in NYISO, New York’s power market.

While Microsoft may have pockets to afford this $13 billion expense over 20 years, it speaks to the underlying economic challenge. The two restart projects require off-market PPAs or grants for viability. They are not competitive in pure market terms and must be subsidized by the government or by hyperscalers’ discretionary carbon goals.

Since electricity is the largest variable cost in datacenters, it seems inevitable that power purchasers become quite a bit more price conscious as products are commercialized, profitable margins are required, and players compete.

Meanwhile Small Nuclear Reactors (SMRs) face three critical challenges.

They don’t exist. NuScale’s first VOYGR plant is now projected to be operational by the early-to-mid 2030s, following the cancellation of its Carbon Free Power Project in 2023 due to cost overruns. Other companies like Oklo and TerraPower Energy are targeting ~2030 for their first reactors, but significant technical, regulatory, and supply chain challenges remain.

They won’t be cheap. Beyond technical feasibility, there is little evidence to suggest such projects will be economically viable, especially in their early iterations.

They are small. If the goal is to meet gigawatts of new demand, “small” reactors seem counterintuitive. Even if early prototypes are delivered, they will not reach a threshold of materiality in the power market in the next decade.

Despite the hype, incremental nuclear generation will not supply the electricity that is expected to be required over the coming years. Subsidies, restarts, and new power agreements will simply maintain overall nuclear power generation at its current levels.

So what should we make of public market action? Let’s take a look at some power producers, miners, and SMRs that have been riding the hype.