The Great Moderation

#88: When Macro Gets Boring.

It’s not a surprise that something called a “Beige Book” isn’t exactly a page turner.

The octonary survey of business conditions published by the Federal Reserve is a collection of “anecdotal information on current economic conditions in its District through reports from Bank and Branch directors and interviews with key business contacts, economists, market experts, and other sources”. Essentially, it’s a formal documentation of the scuttlebutt.

Like all soft surveys, the BB is subject to biases: human, political, selection, and otherwise. But unlike other surveys, like the University of Michigan Consumer sentiment or Purchase Manager Indexes, the Beige Book does not even attempt to turn its qualitative data into some sort of number that can be readily broadcast as GOOD or BAD1. If you want to interpret the Beige Book, you have to read it.

After sifting through the fifty or so pages of the taupe tome, an overarching trend often emerges. During the period of rising inflation, the theme of price-pressure was omnipresent, infecting seemingly every corner of the country’s commerce. Other of the key macro trends we have witnessed over the past several years — supply constraints, labor shortages, booms and busts in manufacturing and housing — have been quite apparent in the anecdotal commentary.

The January 2024 Beige Book, released this week, is pretty boring. Consider the summary:

“A majority of the twelve Federal Reserve Districts reported little or no change in economic activity since the prior Beige Book period. Of the four Districts that differed, three reported modest growth and one reported a moderate decline.”

Snooze2.

But a deeper read of the report depicts a varied economy, with pockets of geographic and sectoral strengths and weaknesses. Manufacturing remains weak, but consumer activity has improved. Housing activity is still in the dumps, but easing mortgage rates provide a twinkle of optimism. Anxiety over commercial real estate persists, but business expectations for the year ahead are positive. Labor markets are easing across the board, with lower churn and higher applicant pools, but overall employment continues to grow. Price pressures, thankfully, continue to subside.

There is no single BIG ISSUE that dominates the commentary. And all the BIG ISSUES from the past several years seem to be moderating. The words “modest” or “moderate” qualify almost all directional commentary. (Overall, this is an improvement from much of 2023 as references of “weakness” have subsided).

After several years of wild swings in macroeconomic conditions, a return to normalcy can be disorienting, like stepping off a boat and feeling that the solid ground is in motion. But I think an economy with weakness and strengths, hopes and anxieties, is normal. On balance, real growth typically trudges forward. The Great Moderation is underway.

Puts and Takes

It’s not that some economic data isn’t concerning. Rather, it’s that most negative facts can be countered with some sort of positive. Take, for example, the ISM Services Purchase Managers Index (PMI) that showed a massive drop in the “employment” sub-index for December.

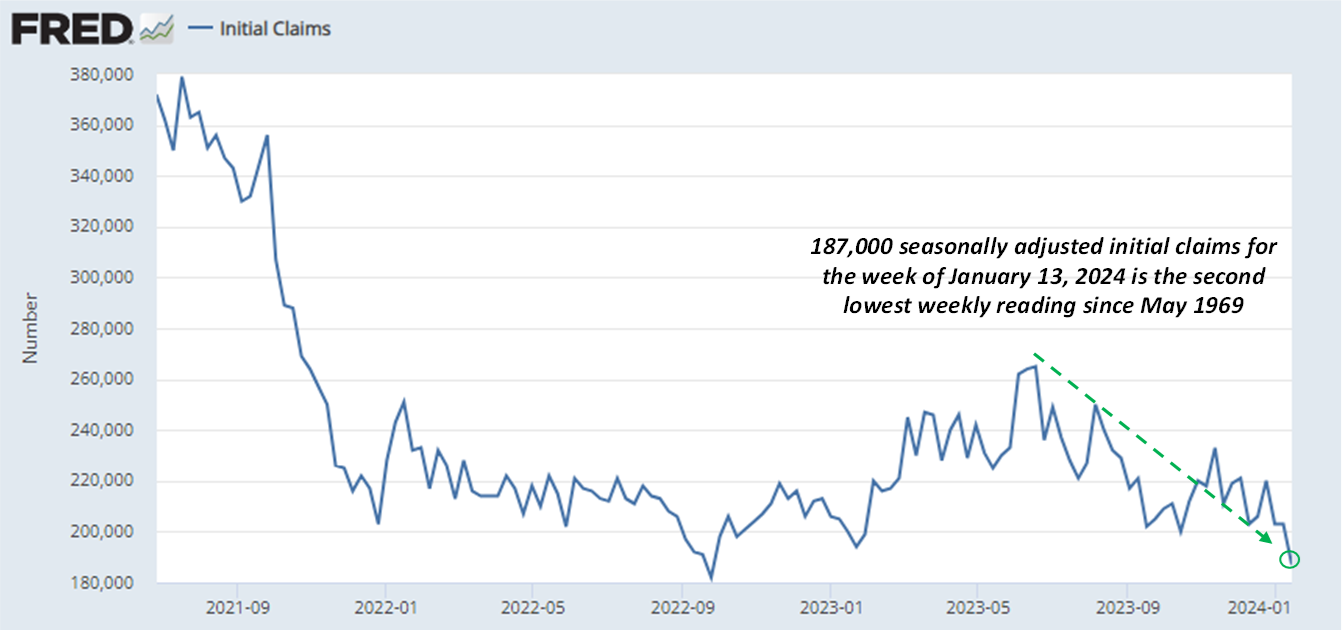

In isolation, such a chart looks like an ominous (albeit noisy) collapse in the labor market. But on the other hand, latest seasonally adjusted initial unemployment claims, which have continued a pattern of decline since mid-2023.

At 187,000, the most recent initial unemployment claims are the second lowest on record going back to May 1969. Continuing unemployment claims have also fallen in recent weeks, and the series is roughly unchanged since March of 2023.

Similarly, the ongoing weakness in the manufacturing sector described in the Beige Book is an old story. The COVID-era goods-boom energized activity in 2021, but eventually led to massively overstocked inventories as consumer spending shifted back towards services. Since October 2022, the ISM Manufacturing PMI has reported 14 straight months in contraction (<50), the longest streak since 2000-2021. But if we look at the series, does it not appear that the worst is behind us?

Metrics of freight activity seem to support this idea. Freight volumes on both trains and planes bottomed in mid-2023, and have turned sharply higher in recent months.

Further support for a manufacturing rebound comes at the point of sale. The Johnson Redbook Index, a measure of year-over-year same-store sales growth at retailers, decisively bucked its downward trend in mid-2023 and seems to be holding at a healthy 5% annual increase.

Again, consumer spending has generally exceeded expectations in the back half of 2023, as indicated by both hard and soft data. One way to see this numerically is in total consumer credit outstanding. Contrary to some interpretations, growing consumer credit is a sign of a strength in the economy, indicating both a willingness to spend and a willingness to lend.

Consumer credit had slowed substantially through the first half of 2023, flashing warning signs of economic weakness. But since August 2023, activity has rebounded noticeably — just around the same time that Redbook and freight metrics began to improve.

In housing, which has been hamstrung by higher mortgage rates for the past two years, the easing in interest rates since October has already translated into increased activity. The Mortgage Bankers Association’s index of mortgage applications has ticked up in recent months mirroring the decline in rates.

Both due to easing rates and annual housing seasonality turning positive, we should expect to see a slew of upbeat housing data over the coming months.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that there is some massive boom in economic activity underway. Manufacturing is still in technical contraction, but is showing signs of improvement. In the larger services sector, activity remains positive by most measures, but is down significantly from the post-COVID peaks. Taken together, the pluses and minuses seem to be netting out to something much more mundane.

Indeed, the composite PMI for the US has hovered just above fifty, indicating moderate, or modest growth in aggregate.

Implications

The past several years have been quite unusual. There was a pandemic, a rebound, and a hangover. Inflation, rates, and liquidity have swung wildly. Services and manufacturing diverged dramatically, befuddling traditional macro models. Indeed it was a very challenging, but admittedly exciting time for economic watchers.

But as we move further away from these disruptions, an equilibrium eventually emerges. Water finds its level. This, in my opinion, is the overarching theme of 2024 so far: The Great Moderation.

This is a good thing. As uncertainty wanes, businesses will have more confidence in planning and expansion. Smooth and steady is not sexy but rather sustainable. My base case for the year ahead is that we continue to see modest, moderate, and frankly boring growth.

Regarding monetary policy, the two biggest concerns for the Fed are inflation and employment. Even as economic growth continues, price pressures and wage pressures continue to subside. This gives room for the widely expected “normalization” of monetary policy — i.e. some number of rate cuts, and a tapering or pause of quantitative tightening.

Fiscal policy, particularly in an election year, should continue to provide a tailwind.

Of course risks remain. The greatest risk, in my opinion, is that “easing” in labor markets, which can be seen across soft surveys, JOLTS data, temporary workers, and so on, turns into an outright contraction in employment. A contraction in employment would negate the positive outlook above, and likely would lead to recession. I will continue to watch labor markets closely, and will be sure to update readers accordingly.

A secondary risk — for markets in particular — is an uptick in inflation. If the market re-prices the easing of monetary policy, it would have an immediate negative impact to bonds and rate-sensitive stocks, and longer term negative impact to certain real economic sectors, including housing and commercial real estate.

Next week, we take a deeper dive into a decidedly not boring economy - China.

Thank you for reading The Last Bear Standing. If you enjoyed this post, hit the like button and share it with a friend. Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

TLBS

The best attempts to quantify the beige books often are simple word counts — how many times did “weak” or “slow” appear? But this is a pretty rough proxy. For example, “moderate” may refer to an increase or decrease.

Admittedly, describing a particularly mundane installment of a generally mundane series is probably not the best strategy to keep you engaged in reading this article, but I swear I have a point.

Macro can get boring but not the Mr. Bear's articles ;)

Thank you for your insights sir!

Thanks for the explainer and your interpretation.

Is it titled “Beige” in homage to the mundane colour of the same name?