The Death of QT

#46: Just like last time, it ended with a bang.

The Fed failed in its one previous attempt at liquidity tightening. Now, embarrassed and headstrong to tackle rampant inflation, the Fed seems likely to repeat its mistakes.

-Down the Drain, June 16, 2022

For the past year, this column has repeatedly warned that Quantitative Tightening (QT) would result in failure and force the Federal Reserve into another round of emergency liquidity injections, just like the repo crisis of September 2019. And just nine months after the official start of QT, here we are.

After draining a trillion dollars of cash out of commercial banks1, QT bagged its first victim. Silicon Valley Bank went bust, setting off a chain reaction of contagion and panic in the process2. To quell the panic, the Fed backstopped uninsured depositors of the elite institution and invented a new emergency lending facility3 for other banks in distress.

The latest Federal Reserve balance sheet data released on Thursday afternoon reveals the scale of new liquidity provided to the banking sector. In the past week, the Fed’s balance sheet expanded by $297 billion4, reversing about half of the cumulative effect of QT to date.

How is it possible that a liquidity crisis could occur so early into QT, and after the enormous monetary expansion of the prior two years? The Fed expected that QT would run in the background for years, reducing the overall size of its balance sheet by trillions. Instead, the Fed found itself frantically subduing a bank run.

Rather than spill more ink on this week’s banking crisis, lets instead diagnose where the QT went awry.

The answer lies in the plumbing.

Monetary Plumbing

Here is a rough model of modern monetary plumbing5, split into four major components.

In Green is the money printer / money shredder. When the Fed buys Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities in Quantitative Easing (QE), or lends to banks through liquidity facilities or the discount window, it creates new dollars which increases the Fed’s balance sheet and reserve balances at commercial banks. Conversely, during QT, money flows out of the commercial banks and the Treasury General Account as bonds held by the Fed mature and are repaid. These dollars are shredded and the Fed’s balance sheet declines.

In Orange, is the Treasury General Account (TGA) - the government’s bank account at the Fed. When individuals pay taxes or when the Treasury issues new debt, money flows out of commercial banks and into the TGA. When the Treasury spends the money, the cash returns to commercial banks. During QT, the TGA also funds maturing Treasury securities held by the Fed.

In Red, is the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP). The purpose of the RRP is to set a floor on overnight interest rates by providing the private sector the opportunity to lend money to the Fed at a fixed rate (4.55% today). The RRP is used primarily by money market funds (MMFs) as an alternative to other short-term investments. When a MMF puts money into the RRP, it removes cash from the banking sector.

Finally, the remainder in Blue is the cash in commercial banks. Importantly, the commercial banking sector has very little ability to control the aggregate level of cash it holds. Banks do not control QE or QT, the ebbs and flows of the TGA, or RRP usage6.

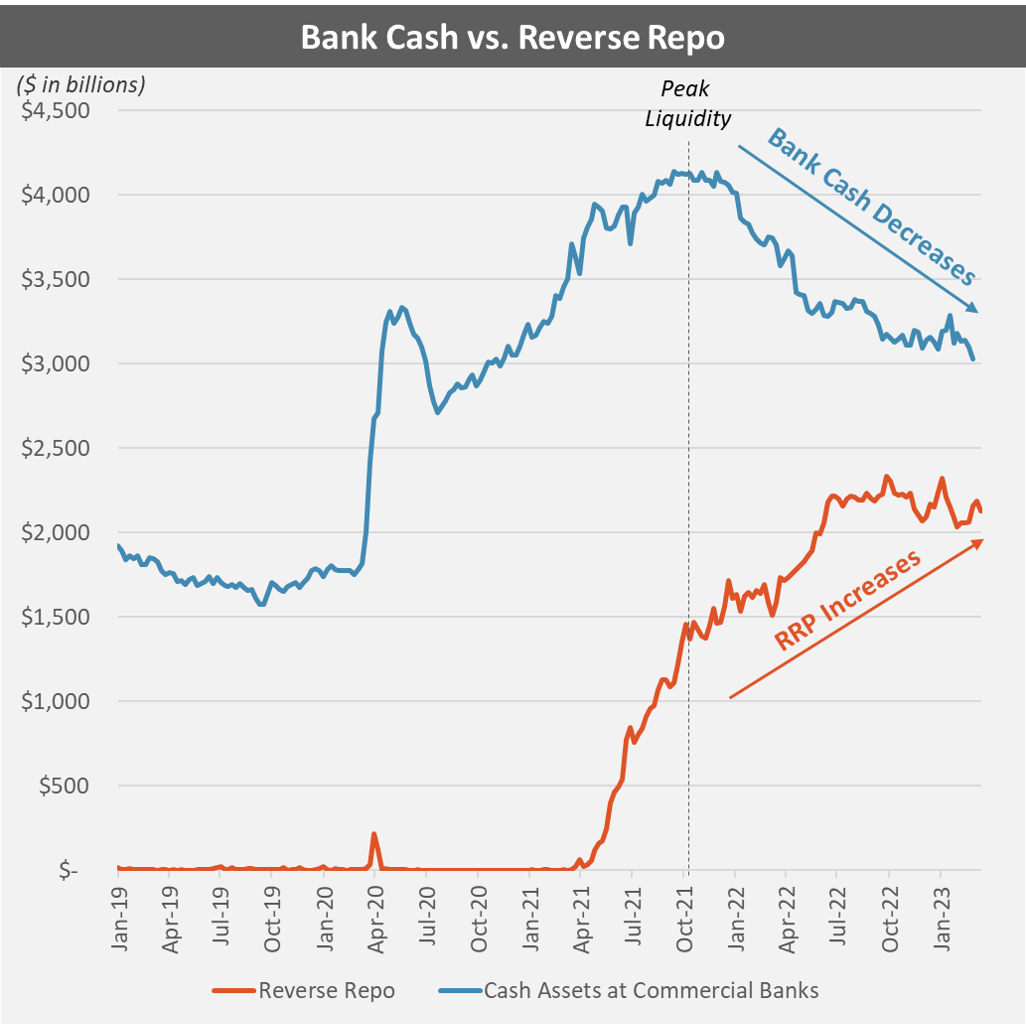

As the Federal Reserve reduces liquidity via QT, it must also consider these internal dynamics to understand where the money is coming from, and whether commercial banks have adequate reserves. Since late 2021, bank reserves have been falling while RRP balances have grown to over $2 trillion, where they remain stubbornly sticky.

If the Fed believed that bank reserves and RRP balances were free-flowing and fungible, they haven’t been paying attention. The Fed has repeatedly ignored this concern and instead stood by as dwindling cash balances at commercial banks sparked a banking crisis.

“They Don’t Need the Cash”

During an interview in January, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller explained the central bank’s perspective on the interplay between the RRP and QT.

“We have a standing Reverse Repo facility, and every day firms are handing us $2 trillion of liquidity they don’t need. They give us reserves, we give them securities. They don’t need the cash - $2 trillion a day!

So I’ve made this argument, ‘It sounds like you should be able to [reduce the Fed’s balance sheet by] $2 trillion and nobody will miss it’, because they are already trying to… get rid of it…

If banks need reserves, it’s sitting over there in the RRP, being handed over by Money Market Mutual Funds. They are going to have to compete to get that back.”

MMFs are not giving away liquidity they don’t need. MMFs take investor money and lend it to someone. The RRP allows MMFs to lend directly to the Fed and earn a risk-free, zero-duration 4.55% return in the process. MMFs are not giving away excess cash, the Fed is giving away free return.

The entities that are losing liquidity are the former borrowers of MMFs who have been boxed out by the Fed, and those borrowers’ banks who would have held that money. The liquidity needs of these entities (and their banks) have not changed, but they have no say in the matter.

In other words, the RRP balance is not excess liquidity in the financial system - it is liquidity that has already been removed from the financial system. Ironically, Waller is looking at the single biggest drain on banking reserves and interpreting it as license to tighten liquidity even further.

Waller also acknowledges that QT can’t be directly be funded the RRP (as demonstrated by our diagram). Banks must first lure cash away from the RRP.

There are two ways this could happen - either MMFs investors could pull their money to get a better return as a bank depositor, or MMFs could choose to leave the safety of the RRP and lend directly to banks. The former will not happen because bank deposit interest rates are negligible. The latter won’t happen because wholesale funding rates only dislocate from the Fed’s target rate in moments of financial stress, when the safety of the RRP is most valuable.

All of these factors should be well understood by the Federal Reserve, if not academically then in practice by observing the cash dynamics over the past year7. Instead, the Fed counted on the RRP to provide liquidity as QT drained non-GSIB banks of their last reserves.

Here is the irony. As banks borrowed hundreds billions from the Fed’s emergency facilities this week, the MMFs were right around the corner lending trillions back to the Fed.

The End of Tightening (But Not Yet QE)

So, is Quantitative Tightening dead?

The purpose of QT was to remove “excess” cash from the banking sector in order to constrain bank lending, credit extension, and the organic growth of money supply. Today, there’s not much excess cash left in the banks to remove.

Unless the RRP drains bank into banks, there isn’t much room left to tighten. As it is, the need to refill the Treasury General Account after resolution of the debt ceiling will draw a meaningful amount of remaining bank liquidity.

Therefore, it seems unlikely that QT can go on much longer without further exacerbating the challenges in the banking sector. Whether the Fed agrees and how it may choose to signal a change of plans is up in the air. We await the FOMC next week.

But this recent balance sheet expansion is also not QE.

The Fed’s balance sheet grew due to (i) $142 billion to fund the FDIC takeover of SVB and Signature Bank (ii) $12 billion of uptake under the new BTFP facility and (iii) $140 billion of net new discount-window borrowing. The $152 billion combined BTFP and discount window borrowings are direct asset swaps between banks and Fed - so while it increases bank liquidity, it does not create new deposits.

This intervention is more similar to the liquidity injections of 2008 which swapped bank assets for cash directly, as opposed to the COVID QE which created new deposits by buying bonds from non-bank entities and directly expanded the money supply in the process. In this sense, it is less likely to exacerbate inflation based on its first-order impact.

Now, whether the stock market cares about those technical distinctions is another question. The overwhelming message is that while inflation is merely a nuisance to central bankers, financial instability is their kryptonite - and in each instance financial disruption will be met with immediate accommodation. For now, that’s all the market needs to know.

If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, please subscribe, hit “like”, and tell a friend! Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

As always, thank you for reading.

-TLBS

As we’ve written before, the QT began far before its official start date in June 2022. Cash in the banking sector peaked all the way back in late 2021 and had already fallen substantially by the time QT officially began.

Last week, we put forth a relatively sanguine assessment of U.S. banks, and instead pointed to non-bank financials and the fixed income market as a more likely source of liquidity stress (as was the case with U.K. pensions). This premise was based on the stronger balance sheets of domestic Globally Systemically Important Banks (“GSIBs” - J.P. Morgan, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Bank of America), and the fact that banks hold a relatively small portion of the overall bond market, which has experienced losses as a result of rate hikes.

Clearly, last week’s assessment was wrong.

Hours after publishing, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed in dramatic fashion, prompting fears of contagion and a cascading bank run of similarly positioned regional banks. Over the weekend the Fed, the FDIC, and the Treasury announced emergency measures to shore up confidence in the banking system.

In an interconnected system, the weakest link is often more important. By focusing exclusively on more highly regulated GSIBs, we underestimated the risk in under-regulated small and regional banks and the role that panic and contagion can play in bank runs. Painting with a broad brush proved dangerous.

The Banking Term Funding Program, or BTFP. So close to BTFD.

The balance sheet expansion includes the amounts required by the FDIC in their takeover of SVB and Signature, as well as new borrowing from other banks through the Fed’s discount window and the newly created Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

We discuss these dynamics in greater detail in Down the Drain.

The interest rate that banks earn on their cash balance is slightly higher than the RRP interest rate, meaning that banks are not directly utilizing the RRP. Rather it is MMFs who choose to withdrawal cash from banks and place it in the RRP. Banks have no direct control over flows in or out of the RRP.

Or perhaps by reading this blog.

Awesome analysis! The correlation pointed out is between cash decrease and repo risk increase. How does the Fed not understand this correlation? Most likely is that they fully understand but are penned in.

Watch out for Sept 2019 redux.

Great piece on RRP and how they trapped themselves, drowning in liquidity. It is appalling to see Waller's ineptitude in misinterpretation of RRP inflow - how can you not see that the MMFs and others are taking a risk-free ride from the Treasury?

What's your take on the TGA now running into deeply negative (deficit monetary policy) territory since all the QT liquidity drainage? I think that will break something in the mid-to-long term.

Afaik they almost never dipped into that vast crevice of negative income in the TGA before 2008/9 and then it recovered thanks to massive QE... which is now ending (rather: being ended).

This is going to be (no) fun since I still see a drop in S&P on 2008/9 levels highly possible with all this.