Spotlight on the Treasury

#35: On the Treasury General Account, the debt ceiling showdown, and implications for the market.

We are six months into official Quantitative Tightening (QT), and so far, it has been fairly uneventful. Equity and fixed income markets have remained orderly even while trending lower.

But this isn’t proof that QT is benign and can be absorbed without a hitch. Rather, market liquidity has only marginally tightened since headline QT began in June.

It’s not that the Federal Reserve is lying about the pace of balance sheet roll-off (as some folks continue to speculate). Instead, net liquidity is driven by a complex interplay between the Federal Reserve, the U.S. Treasury and the private market, which obscures both the pace and timing of true tightening (as detailed in Down the Drain)1. Ironically, liquidity shrank at a faster pace in the first half of 2022 before QT officially began, than it has in the second half of the year2.

A majority of the Fed's balance sheet reduction since June has been offset by a reduction in the U.S. Treasury’s cash on hand in the Treasury General Account (TGA)3. The drawdown of the TGA has muted the impact of QT to date and will continue to play an important role for market liquidity in an unusual way in the year ahead.

Funding QT

When the Federal Reserve purchases U.S. Treasury securities (“USTs”) during Quantitative Easing (“QE”), it effectively loans money to the federal government4. Now, the Federal Reserve is allowing that debt to come due, and the Treasury will be forced to replace financing from the Fed with new financing from the private market.

As the Fed’s holdings of USTs mature, dollars flow out of TGA to pay back debt owed to the Fed. In other words, the Treasury must fund the majority of QT - up to $60 billion per month5. Just as QE “prints” money by increasing dollar supply, this repayment from the Treasury to the Fed “shreds” dollars, and the Fed’s balance sheet shrinks in the process.

But this payment between the Treasury and Fed does not directly impact private market liquidity, it is merely a transfer of dollars between accounts at the Fed which reduces the Treasury’s cash on hand. The true impact of QT occurs as the Treasury refills its coffers by issuing new debt, pulling cash out of the private financial market in the process.

In the year ahead, the Treasury will need to fund the ongoing federal deficit (estimated at $1.2 trillion), increasing interest burden on existing debt, plus an additional $720 billion of QT repayments to the Fed. To accomplish this feat, the Treasury must issue (and the private sector must absorb) an enormous supply of new USTs.

There is just one small problem - the Treasury can’t issue more debt.

The Debt Ceiling

It was just over a year ago, on December 16, 2021, that congress last raised the debt ceiling. After much handwringing and political infighting, lawmakers eventually agreed to a $2.5 trillion extension, raising the limit to $31.385 trillion.

Today, the total outstanding public debt stands at $31.336 trillion - just a hair under the new statutory limit - setting the stage for yet another debt ceiling showdown in 2023.

Despite reaching the ceiling today, it will be months before the federal government runs dangerously low on funds and the threat of default becomes real again. There is $434 billion remaining in the TGA today, and there are several “extraordinary measures” that the Treasury can utilize to free-up cash (which provided roughly $300 billion of incremental funding in the last go-around). Most estimates put the true deadline for a new extension in 3Q 2023, though it is impossible to forecast with precision6.

Conventional wisdom says that the debt ceiling makes for scary headlines but doesn’t represent a real risk - it’s just political brinkmanship. The consequences of a federal default would be so disastrous that even our worst politicians would ultimately relent to compromise (or so the thinking goes). After all, the ceiling has been successfully lifted 78 times, and the country has never defaulted.

However, in the context of ongoing QT, the debt ceiling has unique and counterintuitive implications.

Until the debt ceiling is lifted, the Treasury will continue to use cash on hand to service its expenditures (including QT). Absent this limitation, the Treasury would choose to issue more debt today to maintain a comfortable TGA balance rather than drawing down its cash reserves to extreme low levels7.

This uncomfortable situation for the Treasury is “good news” for net liquidity in the near term. Ironically, the debt ceiling prevents the Treasury from drawing more funding from the private financial market.

This dynamic is already playing out. On October 31, the Treasury estimated it would end the year with a cash balance of $700 billion assuming that the debt ceiling would be lifted. Instead, the TGA stood at just $434 billion as of December 21. That means that the Treasury planned on issuing $264 billion of incremental net debt over the past two months but was prevented by the debt ceiling.

The real concern is what happens after the debt ceiling is lifted when the Treasury can once again tap the market for funding. At this point, we should expect massive new UST issuance as the TGA is refilled and a corresponding reduction in the monetary base, cash at commercial banks, and market liquidity8.

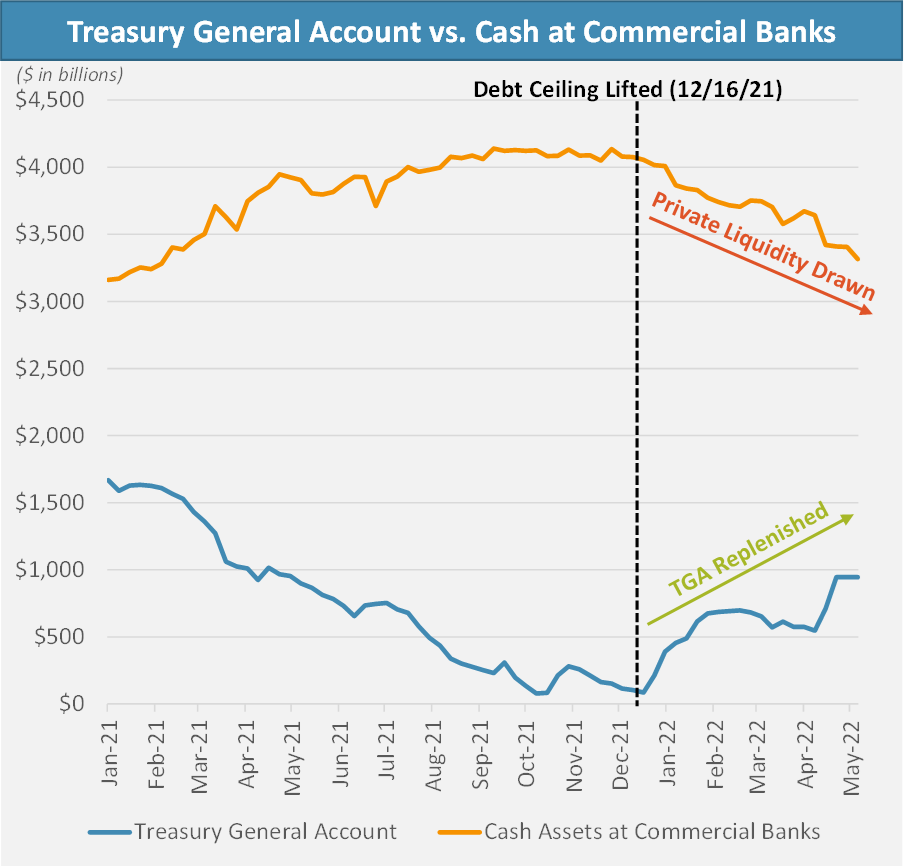

This is precisely what occurred as the debt ceiling was lifted in 2021. As soon as it was able, the Treasury hit the market to replenish its depleted cash balance, drawing down cash assets from commercial banks in the process. From mid-December 2021 to May 2022 the TGA balance increased by $906 billion, while cash at commercial banks fell by $760 billion.

While this example provides a directional roadmap of what to expect in 2023, the backdrop will be much less forgiving. Back in 2021, the Fed was still expanding dollar supply via QE, and there was much more liquidity available to absorb. Today, market liquidity is already greatly diminished, and the Fed is shredding up to $95 billion a month.

Big Picture

How will the Treasury continue to fund massive budget deficits with its interest expense rising dramatically, remittances disappearing, and while the Fed is calling back its QE loans and reducing available liquidity in the process? These are the looming big picture questions facing the Treasury.

Yet, in the short term, the Treasury is stuck with a more familiar and pressing obstacle - raising the debt ceiling and avoiding default. Without the ability to raise new debt, the Treasury will continue to fund QT with all available cash on hand until the ceiling is eventually raised. While this dynamic may benefit the market in the near term by pushing off the inevitable re-load of the TGA, it will only exacerbate the Treasury’s challenges once the limit is lifted.

To be clear, the TGA is not the only factor that impacts liquidity in the private market. Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) roll-off will continue at a maximum pace of $35 billion per month, shredding cash from the private sector as homeowners make their mortgage payments. Further, Reverse Repo (RRP) balances will continue to fluctuate daily, adding and removing liquidity in the process.

But as we enter the new year and discussion of the debt ceiling grows more pressing, expect the spotlight to focus on the Treasury.

I wish you all the best in the New Year! It has been a pleasure to write for you this year, and I’m looking forward to bringing you even better content in the year ahead.

As always, thank you for reading. If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, like this post and tell a friend! And please, let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

-TLBS

For newer readers, I’d recommend reading Down the Drain to get a baseline understanding of the interaction between the QE/QT, the Fed’s balance sheet, the Monetary Base, the Treasury General Account, and the Reverse Repo facility. Down the Drain remains the most popular TLBS post to date.

Recall, “peak liquidity” occurred back in December 2021.

Since QT began in June, the Reverse Repo facility (RRP) balance has grown slightly, while commercial bank reserves have fallen marginally.

At least indirectly, by buying these debt securities from a private market participant. One way to think about this is that the private market provided the Treasury and homebuyers a “bridge loan” that was taken out by the Fed in the secondary market.

The remainder is funded by mortgage borrowers - U.S. homeowners - as they make their regular mortgage payments.

And my own back-of-the-envelope math suggests the deadline may come sooner than expected.

By the time the debt ceiling was lifted in December 2021, the TGA had fallen below $100 billion and all “emergency measures” had been exhausted - meaning the Treasury was truly on the brink of a default. The situation became so extreme that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was writing letters to congress on a weekly basis to emphasize the risk of default and urge congressional resolution.

Other things equal, assuming no change in RRP balances.

Nice post to end the year with. 2023 should prove to be damn interesting.

A couple of points:

1. Regarding footnote 5. Its actually the principal from prepaying mortgages that makes up the majority of monthly MBS payments to the FED. The principal portion of regular mtge payments is ~5b/mnth on the FEDs 2.6T MBS portfolio, thus prepayments accounted for ~12b of the FEDs MBS reduction this month. Prepayments used to dominate much more before mtge prepayments speeds collapsed. Since the 5b/mnth for regular principal payments is close to static, when the FED was receiving 40b/mnth in MBS payments (early last spring) the split was more 5/35. Sorry for the nitpick but thought you and your readers might find the nuance interesting.

2. Treasury's payments to the fed to payoff UST maturities each month is debt ceiling neutral I believe since regardless of whether its the FED (reinvestment above the QT cap) or rest of market (up to the 60b cap) that funds the rollover, from a debt ceiling perspective its maturing debt so Treasury can reissue the same amount of debt without impacting the debt ceiling number. So I think its really the deficit spending (including servicing costs for existing debt) that drives the TGA drawdown once the debt ceiling is hit and the only new debt Treasury can issue is rollover of maturing debt (in amounts anyways composition of the new vs. maturing debt may change e.g. Bills -> coupons to keep the coupon issuance schedule)

3. One thing to account for on when the TGA will exhaust in the absence of a ceiling hike is tax receipts. My general understanding is they are heavier through April/May which would offset pressure on the TGA drawdown for a bit and may explain why many estiamtes dont anticipate exhaustion until Q3

4. My last point is more a question. What is the causal relationship (if any) between base money "liquidity" and equity prices/S&P level. Defining base money "liquidity" as more or less the level of bank reserves (total FED B/S liabilities - (TGA + RRP) ) given that currency is pretty constant. I recognize the clear correlation between the two over the past 2 years but I can think of no logical causation. I would love to hear any thoughts you have on that causation or lack thereof. Perhaps an article topic for sometime in 2023.

Thank you TLBS for all you have shared with us this past year! It is fabulous content and very much appreciated.

Happy New Year,

John

Great article as always, very insightful about the mechanics between the treasury the fed and the markets.

Wish you a great 2023!