Re-Funding the Treasury

#56: With the debt ceiling (nearly) lifted, what does Treasury issuance mean for liquidity and the market?

In our final post of 2022, Spotlight on the Treasury, we argued that the debt ceiling and the U.S. Treasury’s financing flows would take center stage in the year ahead.

To wit:

A majority of the Fed's balance sheet reduction since June has been offset by a reduction in the U.S. Treasury’s cash on hand in the Treasury General Account (TGA). The drawdown of the TGA has muted the impact of QT to date and will continue to play an important role for market liquidity in an unusual way in the year ahead […]

Until the debt ceiling is lifted, the Treasury will continue to use cash on hand to service its expenditures. Absent this limitation, the Treasury would choose to issue more debt today to maintain a comfortable TGA balance rather than drawing down its cash reserves to extreme low levels […]

This uncomfortable situation for the Treasury is “good news” for net liquidity in the near term. Ironically, the debt ceiling prevents the Treasury from drawing more funding from the private financial market […]

The real concern is what happens after the debt ceiling is lifted when the Treasury can once again tap the market for funding. At this point, we should expect massive new UST issuance as the TGA is refilled and a corresponding reduction in the monetary base, cash at commercial banks, and market liquidity.

So far, this prediction has been spot on. The debt ceiling ex-date indeed came earlier than many suspected1, and congress has reached a deal to extend the limit just in time to avoid a default. Now, the Treasury is gearing up for a deluge of new U.S. Treasury (UST) issuance to refill its coffers.

This week, we will review the key liquidity flows of the past year and the potential impacts of the Treasury’s upcoming funding plans.

Funds Flows

During the first year of QT, the amount of cash held in the private financial sector has remained relatively steady. On June 1, 2022, commercial banks held $3.35 trillion of bank reserves. One year later, the total is $3.25 trillion - nearly unchanged over the year.

But as we have outlined in prior posts, “net liquidity” is a product of competing funds flows among the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, and the private sector. Over the past year, these flows have broadly offset.

The roll-off of the Fed’s security portfolio (Quantitative Tightening) has been neutered by an almost identical drawdown in the Treasury General Account (TGA). Increased usage of the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) has moderately reduced liquidity, while emergency borrowings from the Fed in the wake of the March bank failures added liquidity into the system2.

Now, however, the Treasury will begin drawing on private sector liquidity, reversing one of the key flows of the past year. The Treasury’s most recent financing plans indicate that the TGA cash balance will increase to $550 billion by the end of June and to $600 billion by the end of September (from a balance of $49 billion as of May 31). With such significant financing needs, commercial bank cash balances could quickly shrink depending on the source of funds.

One common explanation for why RRP balances have remained large and sticky is due to a mismatch between the demand for cash-like short-term investments such as Treasury Bills (T-bills) and their actual availability. Particularly for Money Market Funds (MMFs), which have strict investment criteria, there may simply not be enough high-quality collateral available. So instead, they have sent $2.2 trillion back to the Fed where they can earn the RRP award rate.

Therefore, if the Treasury finances its deficits with new T-bills, it can draw funding from the RRP and leave bank reserves relatively unchanged. Indeed, this is the Treasury’s plan; 66% of the net new borrowings in June 2023 and 78% of the 3Q borrowings will take the form of T-bills.

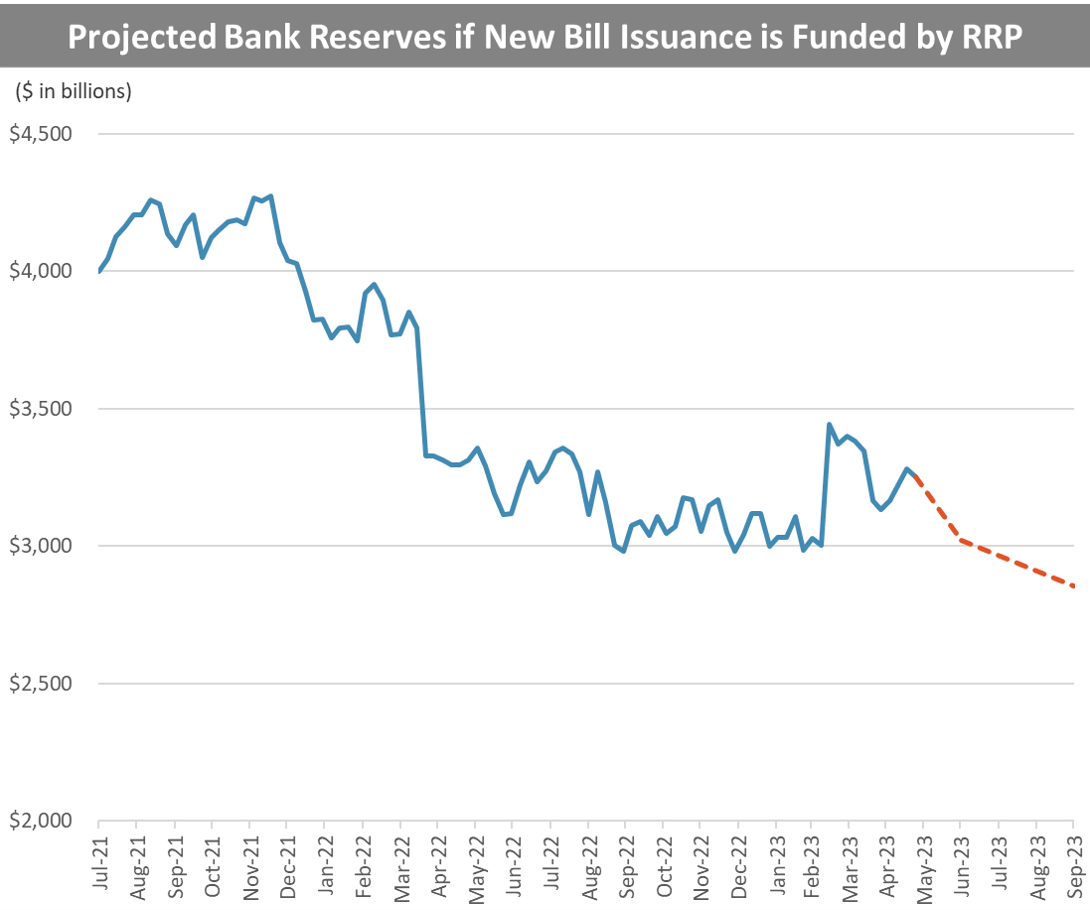

If we assume that a majority of the UST issuance is funded by the RRP, then the net impact on bank reserves will be muted3.

And it’s certainly possible that this plan will work. Higher issuance may push T-bill yields above the RRP award rate, making it economically attractive for MMFs to reallocate their portfolio4. After all, this is how the RRP is meant to work in theory. And if it proves successful, it would provide a clear roadmap for unlocking the huge store of liquidity currently sitting idle at the Fed.

But caution is warranted.

For one, the Treasury auctions are issued on a pro-rata basis to bidders - not selectively to the investment funds that the Treasury prefers. Second, the Fed and the Treasury have long expected that the RRP usage would fall and provide liquidity to the market and so far it hasn’t. In fact, Government MMFs have reduced their holdings of T-bills by $1.3 trillion since mid-2021 in favor of the RRP even as the total supply of T-bills outstanding has risen. RRP balances have only grown even as bank reserves tumbled and several banks failed. Instead, market participants have been forced to the Fed’s discount window or private repo financing.