Origins of Inflation

#20: Analyzing the impact of policy, supply chains, and expectations on inflation.

As we reach the 20th post, I want to thank all of you who have read and supported The Last Bear Standing so far. If you enjoy the column, please continue to share with your friends, click the like button, and add your own thoughts in the comments (I try to respond to all of them). Any and all feedback is welcome!

On Tuesday morning, I participated in a lively Twitter Spaces discussion with a number of other financial commentators hosted by @unusual_whales. Timed with the August CPI report, the topic was inflation and its implication for the Federal Reserve’s policy.

In the discussion, I argued that the Fed’s monetary policy during the pandemic, which led to the fastest money growth in history, was a key driver of the current high level of inflation. Similarly, the Fed’s tangible policy decision’s going forward would have the most direct roll in bringing down inflation.

Others disagreed. They argued that The Fed has very little ability to control inflation. In their eyes, the Fed has been easing policy for forty years without creating inflation. Rather, the cause of today’s inflation was fiscal stimulus, supply chain disruptions, or inflation expectations.

By any measure, there is more money today than there was 2019, and I was surprised that some dismissed this point as irrelevant. But money growth is not the whole story either.

Rather than argue dogmatically for a single position, it’s worth exploring all of these pieces separately, to come to a pragmatic view. Let’s explore:

Monetary Policy

Fiscal Policy

Supply Chains

Inflation Expectations

Monetary Policy

Since the last period of high inflation in the early 1980’s, the Federal Reserve has eased monetary policy. Short term interest rates fell from from 19% in 1981 to 0% for much of the last decade. In 2008, the Fed introduced Quantitative Easing, which it has used both for crisis prevention and to provide general stimulus. Yet, despite decades of loosening policy, inflation remained in check prior to the pandemic.

But to conclude that loose monetary policy is incapable of spurring inflation is intuitively suspect and relies on a gross generalization of Fed policy.

First, while short term interest rate policy has declined overall since the 1980’s, it has not been a straight line. Between 1980 and 2020, there were four distinct interest rate cycles. Following traditional monetary policy playbook, the Fed initially lowered rates to stimulate growth and then raised rates to slow growth. In each case, the cycle ended in a recession and a rapid reduction in CPI inflation.

From 1986 - 1989, the Fed raised short term rates until the Savings and Loans crisis and recession of 1991. CPI fell over 3% during the recession.

From 1994 - 2000, the Fed raised short term rates until the dotcom crash of 2000 and mild recession of 2001. CPI fell over 2% during the recession.

From 2004 - 2006, the Fed raised short term rates until the housing market collapsed, spurring the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2008. CPI fell over 6% during the recession.

From 2015 - 2018, the Fed again raised rates, though the conclusion of the business cycle was interrupted by onset of the pandemic.

Just as interest rates are clearly linked to the business cycle and the real economy, they are directly linked to inflation as well. For example, housing prices in the U.S. increased by 42% from January 2020 to April 2022, which was due almost entirely to lower mortgage rates driven by Fed policy. Unsurprisingly, housing costs are now one of the largest and stickiest drivers of the CPI. By hiking rates today, the Fed is seeking to reverse this inflationary impact by reducing housing values and ultimately housing costs.

More controversial is the roll of liquidity policy, or Quantitative Easing (QE) and Quantitative Tightening (QT)1. Perhaps because it is a relatively new tool, there are widely differing views of the impact of QE and QT on the economy, money growth and inflation2.

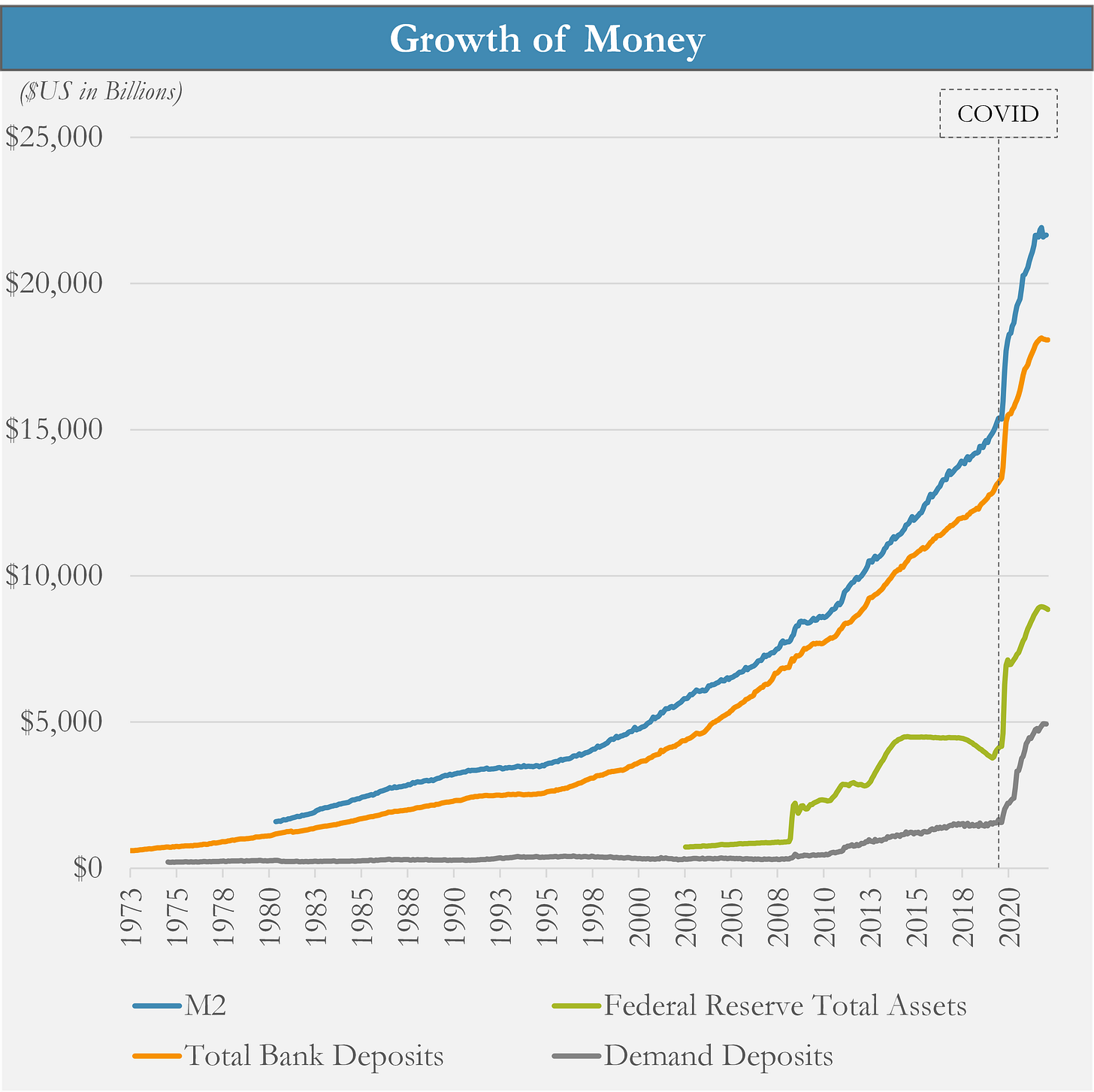

Fortunately, we don’t need to rely on academic arguments because we have real world data. Every single measurement of money grew at the fastest rate on record during the pandemic, coinciding with the Fed’s balance sheet expansion via QE.

M2 - the Fed’s own calculation of money supply - grew at a peak annual rate of 26.9% in February 2021, double the peak rate of M2 growth in the inflationary 1970’s and over four times the 5.9% compounded annual growth rate from 1981 - 2019.

Total bank deposits followed the same trajectory, peaking at 22.6% annual growth - by far the highest on record.

Demand Deposits - the most liquid and spendable form of bank deposits (i.e. checking accounts) - have tripled from $1.6 trillion in February 2020 to $4.9 trillion today, by far the fastest rate of growth ever.

The unprecedented expansion of spendable real-world money was a policy choice of the Fed, enabled by $4.8 trillion of QE during the pandemic. While those policy decisions were taken to stimulate demand in a unique and initially deflationary economic backdrop, it is not without consequence. Put simply, people have far more dollars at their disposal today than they ever have before.

Through the combination of interest rate policy and money printing, monetary policy is a key driver of today’s inflation.

Fiscal Policy

An alternative explanation for today’s inflation is fiscal policy. Congress passed three enormous spending bills in 2020 and 2021 which provided a total of $5 trillion dollars in stimulus largely in the form of direct transfer payments to individuals, businesses, and local governments.

But deficit spending and fiscal stimulus is not a new phenomenon. Since 1974, the U.S. federal government has run a deficit in every year except 1998 -2001. The argument that loose monetary policy hasn’t led to inflation over the past 40 years could as easily be applied to deficit spending.

But such a broad generalization of fiscal policy would be equally flawed. The scale of fiscal deficit during the pandemic and the form of stimulus (direct transfer payments) were both unprecedented outside times of war. This was the first use of “helicopter money” as a policy tool in the United States and was instrumental in transmitting money directly into the real economy.

But here is the critical point missed by many - fiscal policy is enabled by monetary policy. When the federal government runs a deficit, it spends borrowed money. Its ability to borrow is subject to the financial conditions created by the Fed.

The Fed’s interest rate policy determines the government’s cost of borrowing and the Fed’s liquidity policy determines the sheer quantity of money available to borrow. Just consider the comments of Janet Yellen, as reported by CNBC in 2021.

Dating back to her days as Federal Reserve chair, Yellen has long called the nation’s fiscal path “unsustainable,” but has advocated more spending at a time when interest rates are low and the economic recovery remains incomplete.

She subsequently told the committee during Thursday’s hearing that she sees costs to finance the debt remaining “very manageable” as she and other economists see interest rates staying low.

At its peak in July 2020, the balance of Treasury General Account (the government’s checking account) reached $1.8 trillion. This is more than the cash holdings of every single U.S. bank combined just five months earlier in February 2020.

So, where did all this money come from? The Fed printed it.

The COVID fiscal stimulus was effectively funded by the Fed’s QE. Stimulus checks, PPP loans, unemployment benefits, and local government handouts were new dollars, fresh off the digital press, injected directly into the economy’s bloodstream.

Fiscal stimulus clearly played an important roll in injecting money into all corners of the real economy, but the scale of spending was only possible because of monetary policy. Congress has no mandate to ensure price stability, nor does it have the tools to do so. That responsibility lies at with the Fed.

Supply Chains

Supply chain disruptions are, in my view, the least compelling explanation for inflation. The common perception of supply chain driven inflation is that COVID restrictions throughout the globe made it harder for commodities, intermediate goods and final products to be produced and delivered.

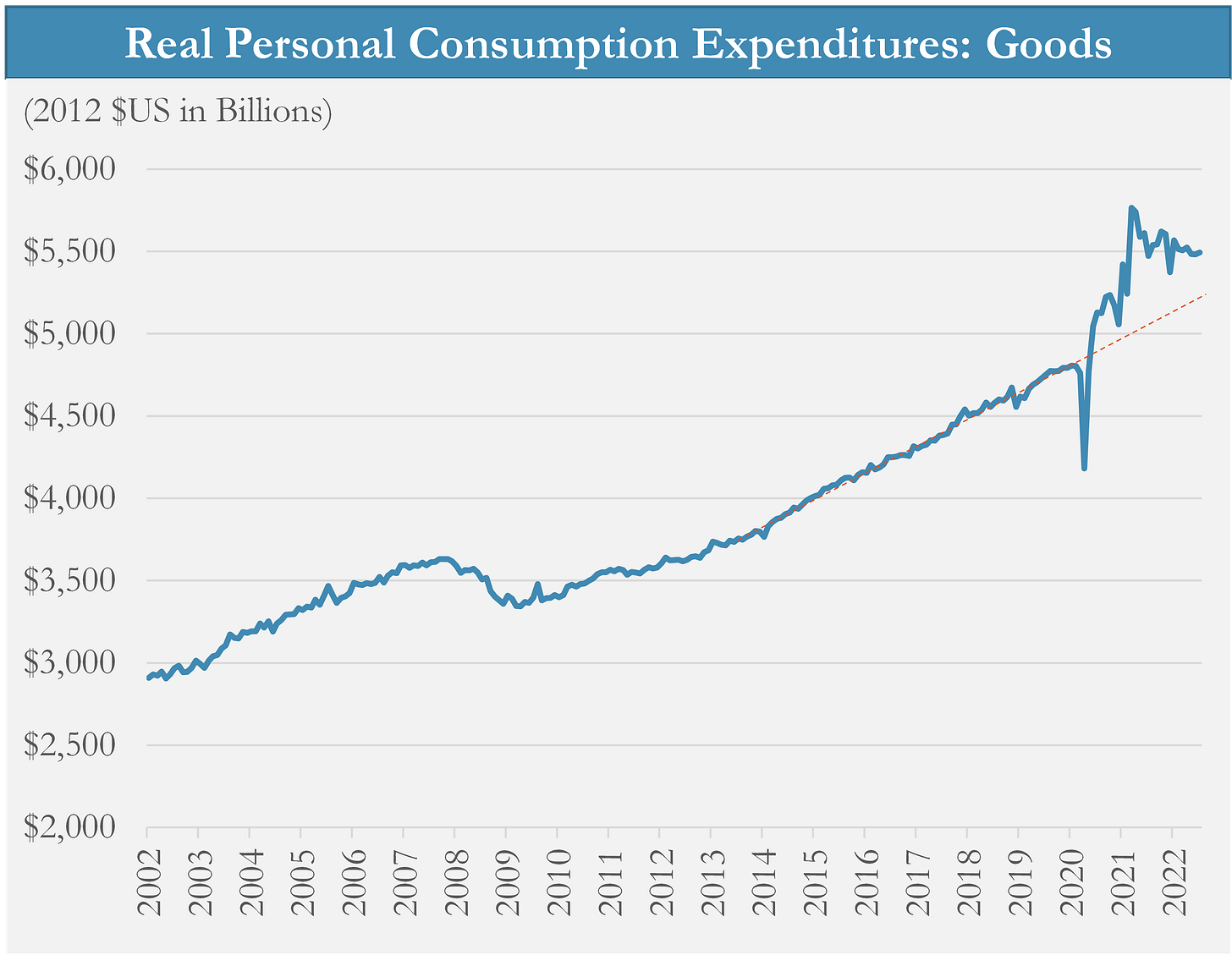

This perspective is not supported by the data. Despite the logistical challenges presented by COVID, supply chains produced (and the U.S. consumed) more goods than ever. In real terms, the country is still consuming far more goods than the pre-pandemic trend.

Over a hundred cargo ships queued off the Port of Los Angeles in the fall of 2021 not because our import capacity had declined, but rather because we attempted to import vastly more goods than ever before. In real terms, the import of goods grew by 20% during the pandemic.

To the extent there were shortages of goods, it was not due to aggregate production or transportation capacity falling below pre-pandemic levels3, but rather that demand grew faster than the supply chains were able to keep up with, despite their admirable attempt4.

Demand grew for two reasons. First, spending was redirected away from services towards consumer goods. Second, personal incomes exploded due to fiscal stimulus, directed by congress and funded by the Fed.

Prior to the full reopening of the economy, there was a reasonable argument that the excess demand for goods would moderate as spending returned to services. Today, we see that both goods and imports remain well above trend even though services spending has rebounded. Further, any moderation in goods inflation has been offset by increasing services inflation.

The problem was never in failed supply chains, it was always excess demand.

Inflation Expectations

A final component worth considering is inflation expectations. The role of expectations is hard to quantify and yet it is the subject of an endless number of academic papers. But sometimes its easier just to look at the data and analyze for yourself.

When simply plotting the University of Michigan surveyed 1-year inflation expectations against CPI, it is hard to argue that expectations are a leading predictor of inflation. Rather it seems that inflation expectations are largely representative of current inflation and changes in expectations generally occur in tandem with CPI5. As a recent example, many have noted that gasoline prices and inflation expectations peaked in lockstep this summer.

By contrast, it is well established that the monetary policy decisions do lead their real-economy impacts by 12 - 18 months. Rate-hike induced recessions often occur a year or more after the Fed has already stopped raising rates. Therefore, it seems far more credible that monetary policy drives inflation while expectations reflect the present circumstance.

Conclusions

Central banks have powerful tools to spur or fight inflation. The most convincing and wholistic argument to help explain today’s 8% inflation starts with monetary policy, the growth of money, and the Fed.

Fiscal stimulus played an important role as well as it directed money growth directly into the economy with a far more immediate inflationary effect. But fiscal spending on such a mass scale was only possible due to the financial conditions enabled by monetary policy.

Shortages of goods are due to excess demand rather than supply chain disruptions or the destruction of productive capacity. Meanwhile inflation expectations appear to be rise concurrently with CPI inflation, not ahead of it.

The mandate of price stability lies with the monetary authority, the central bank. With the great power of money creation comes the responsibility of wielding it. Going forward, it is up to the Federal Reserve to fight inflation. No one else is up for the task.

Liquidity policy is a relatively new monetary tool in the U.S. yet is subject to the same overgeneralizations as interest rate policy. You may hear that “we have been doing QE forever” but this is not true. Prior to the pandemic, there has been just 3 years in total of QE (during parts of 2008, 2011, and 2012-2014), and about a 1.5 years of QT (from 2017 - 2019).

The simple and generally accepted rule is that if the central bank purchases assets from commercial banks then QE does not increase money supply, but if the purchases are from non-bank entities, money supply increases. But even here, there are disagreements on the relevance of different "forms" of money (base money, bank reserves, M2, bank deposits, etc.) and the role each plays in inflation.

Production in certain categories, such as autos, did fall due to shortages of semiconductor components. However this wasn’t due to a shortage in semi manufacturing. The world produced more chips than ever, but they were used up in other goods that were in incredibly high demand like personal computers or bitcoin mining rigs.

The best example of truly impaired supply is in energy markets, where the shut in of production and lack of drilling during the pandemic has now left the world actually short of supply vs. 2019.

Sometimes I lie in bed at night about how unfairly supply-chains have been treated through all of this. I just want to say, if you’re listening, “you did the best you could”.

Perhaps with a mean-reverting bias. Expectations were very high in the late 1970’s but they were lower than CPI. Meanwhile expectations remained between 2 - 4% throughout the last decade even though CPI was below 2%.

Thanks for the great read and your shedding light across all the angles.

I'd like to add to your point of "deficit creation" (aka the state-led inflation of pumping M2) that Bidenomics has seemingly made a miracle possible. They designed something called the "Inflation Reduction Act" that in my eyes will be protracting the inflation curve further through demand-pull inflationary forces - namley in overstimulating ESG investments across the board by subsidizing ESG like Solar Panel/Wind Turbine instalment.

This will likely inflate services and also likely push demand for ESG installations over the available supply, in service time as well as materials/tech needed. "Get it cheaper" will be the driving narrative for ESG providers to drive people to take subsidies and potentially a loan for the rest of the sum for getting Solar installed on your roof.

I am amazed at how much sand you can throw into (media) people's eyes by calling something the exact opposite of what its execution of policies will create.

And this is just U.S. based.

Globally speaking, in core EU there is a whole different beast by overideologized policy driven by the "Need to go Green, whatever it takes" - even freezing one of the world's largest economies (Hint: it's the country of Bratwurst and Beer) over the coming winter and having its energy-intensive industry simply shut down due to unsustainable (read: hyperinflationary) rises in gas / energy cost.

Economy 101 - the same government dictating the stop of energy imports are calling for subsidies, aka creation of more money through ECB in the form of loans to "help the people weather the energy crisis" they managed to maneuver themselves into over the past decades masterfully - that is a true double whammy created by green ideologists to put more oil into the fires of inflation in EU.

This is macro economics 101:

1) Looking from the IS-LM perspectives: if there is only fiscal expansion, nominal interest rate will always rise due to increase in supply of government bonds and/or increased in economic activities and only an equal expansion in monetary policy could keep the interest rate down and keep the economy expanding

2) From a political point of view, no government can get democratically elected by raising taxes and reduced government spending and therefore point 1 is a path of no return. i.e expanding government debt + holding interest rate steady and towards zero

3) The big issue is that only Investment component of the economy get stimulated and as interest rate goes to negative, the percentage of non-productive investment will soar until the point that the non-productive part will consume a large parts of the needed goods and drive up AD curve.