Hype or Hot Air

#131: Are Electric Air Taxis the Future or Fiction?

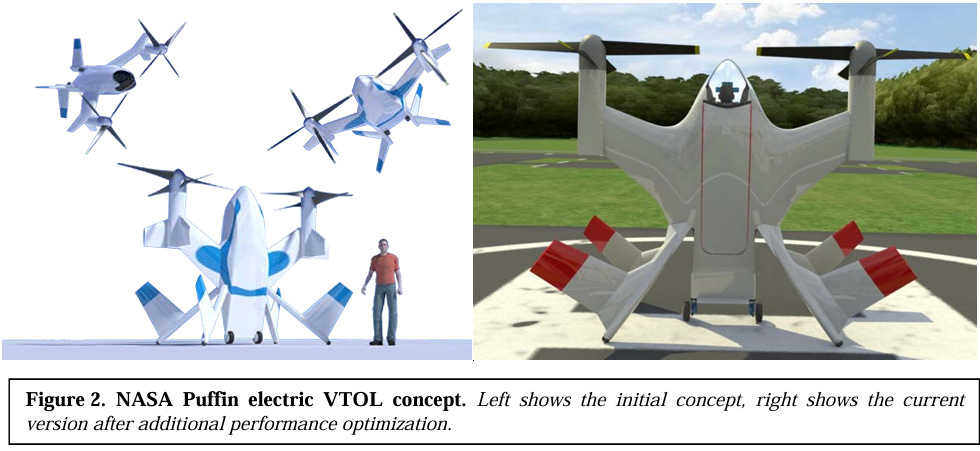

In 2010, NASA unveiled renderings of a strange looking vehicle, seemingly plucked from a low-budget sci-fi storyboard. They called it the Puffin, and it looked like this.

The Puffin was a theoretical prototype for a tail-sitting, one-man flying machine, with two electric rotors — a fully enclosed, battery-powered jetpack. While a little goofy, the concept was meant to demonstrate serious advancements in Distributed Electric Propulsion (DEP) as an emerging form of aviation. Improvements in battery density, aerodynamic modeling, and operational flexibility could begin to unlock electric-powered vertical transportation, creating a new class of propulsion for the first time since the 1940s.

In many ways, this research has already shown its worth. DEP research helped catalyze improvements in small-scale drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), impacting a surprising number of industries; hobbyists, commercial users, and the military. Today, modern drones are capable of transporting loads and demonstrate extraordinarily precise maneuverability, capable of creating remarkable displays in the sky.

Scaling up DEP vehicles for human transportation is an obvious endgame, but has remained elusive. Companies across the world have spent the past fifteen years designing and testing Electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing (eVTOL) prototypes. Some look like big “drones”, while many utilize a hybrid fixed-wing concept with rotating propellers. An online directory catalogues 1,066 total concept vehicles put forward so far.

The key benefits of eVTOLs over rotorcraft are a dramatic reduction in noise pollution, zero local emissions, and reduced fuel costs. These factors could help catalyze public support and subsidies, lead to a significant expansion in supporting infrastructure and usher in a new world of Advanced Air Mobility (AAM).

Publicly listed companies like Joby Aviation (JOBY), Archer Aviation (ACHR), EHang (EH), XPeng (XPEV), Eve Holdings (EVEX), Lilium N.V. (OTC:LILMF), and Vertical Aerospace (EVTL), along with major aerospace companies and private developers are racing to develop and certify eVTOLs and bring forward this Jetsons-esque future.

To date, the primary barriers to commercialization have been technical and regulatory — i.e. designing and building an aircraft, and certifying it under various global regimes like the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the United States. However, less attention has been paid to the economics of this new arena. It often is assumed that these new craft will immediately unlock a massive new market for aerial transport, particularly in dense and congested urban environments. But is this practically true?

As readers may recall, I began to explore this space through my interest in Blade Urban Air Mobility (BLDE), which is one of the only short-distance aerial transportation operators in the world today, using primarily contracted helicopters in New York City and Southern Europe. (The company’s more attractive segment provides organ transplant transportation, mostly via small jet planes). While Blade has always promoted eVTOLs as a long-term catalyst, the company’s actual experience operating “air-taxi” services lends valuable insights into the practical possibilities and economic challenges of this business model.

In this week’s post, I apply a critical lens to this emerging industry, separating fantasy from a realistic future.

Market Sizing and Constraints

Unit Economics and Electrification

Competitor Analysis

Let’s dig in.