Football's Next Season

#120: The NFL opens the door to private equity.

It’s football season. Last night, the defending champion Kansas City Chiefs and the Baltimore Ravens kicked off the National Football League’s 2024 season, an annual tradition that will keep Americans glued to couches on Sunday (and Monday and Thursday (and sometimes Friday and Saturday)) until the Super Bowl.

Despite its detractors, American Football1 remains the goliath of sports and entertainment in the United States — the premiere property in an increasingly fractured media landscape. It’s big business.

And with a fixed supply, few transactions and intangible cultural cache, NFL franchises have become a premier trophy asset — a very public entry into one of the nation’s most exclusive private clubs. In the past two years, we have seen two members of the 32-team league trade hands at eye-popping prices. In 2022, the Denver Broncos sold for $4.7 billion to Walmart heir Rob Walton, only to be topped by Apollo co-founder Josh Harris’s $6.0 billion purchase of the Washington Commanders in 2023.

While the league’s ownership has historically consisted of single families or small consortiums, many of whom have owned their team for decades, the NFL is now slowly opening the door to institutional capital. In August, franchise owners voted 31 - 1 to begin to open the door to private equity, the last of the major U.S. sports leagues to allow such participation. A select group of approved private equity buyers will be able to own up to 10% silent minority stakes in up to six teams each.

For most fans, the idea of private equity entering the league will be viewed with skepticism or indifference. But for nerds like me, questions abound. What would a leveraged buyout of the Jacksonville Jaguars actually look like?

This week, we break down the economics of the NFL, franchise valuations, and private equity’s potential impact on the league.

By the Numbers

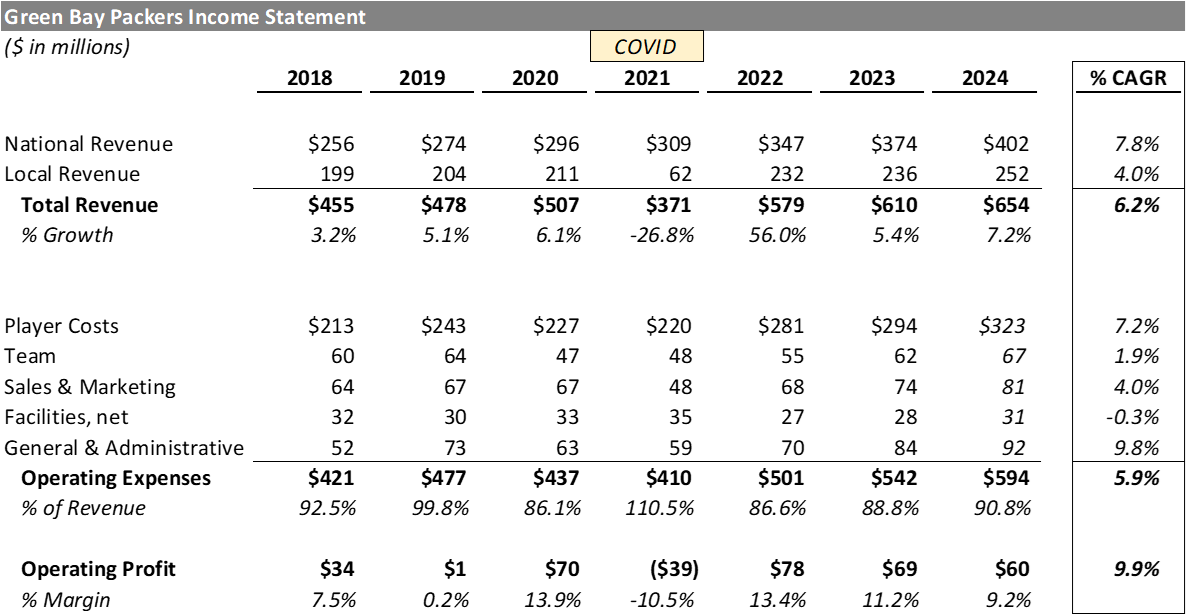

Most NFL teams make a majority of their money from “national revenue” — largely media rights and league sponsorships — which are split equally across teams, and to a lesser extent “local revenue” from ticket sales, team sponsorships, and merchandise which vary from team to team. In the most recent season, national revenue amounted to $402 million per team, making up 65% of total revenue for the average club.

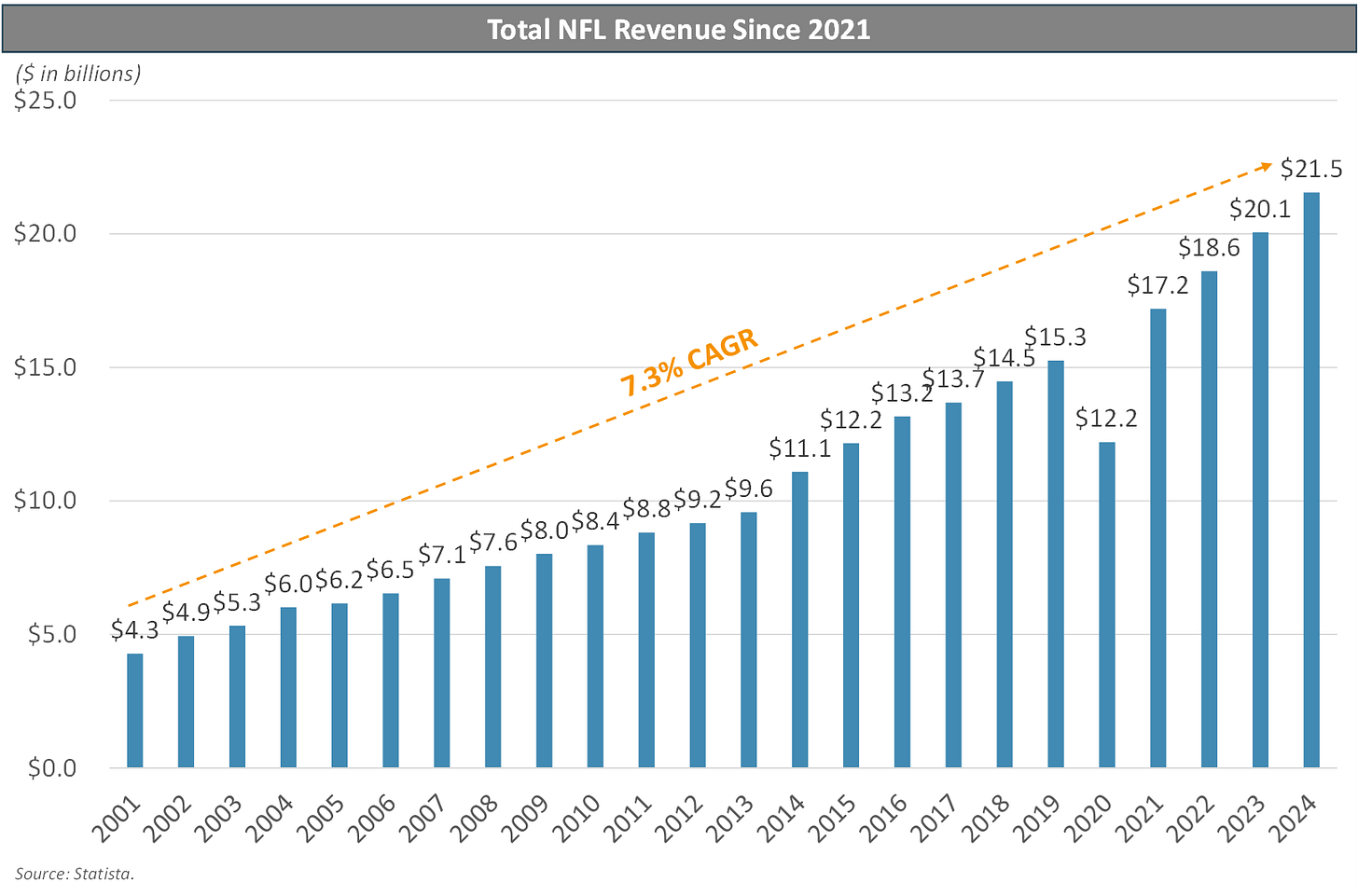

Since 2001, total league revenue has grown at a 7.2% annualized rate, reaching an estimated total of over $21 billion in 2024.

The largest expense is player salary and benefits, which are based on a percentage of revenue (~48%) determined by the league’s Collective Bargaining Agreement and equally distributed across teams by the salary cap.

For an example of a full franchise income statement, we can look to the Green Bay Packers — the only team in the league that is publicly owned and publishes financial statements.

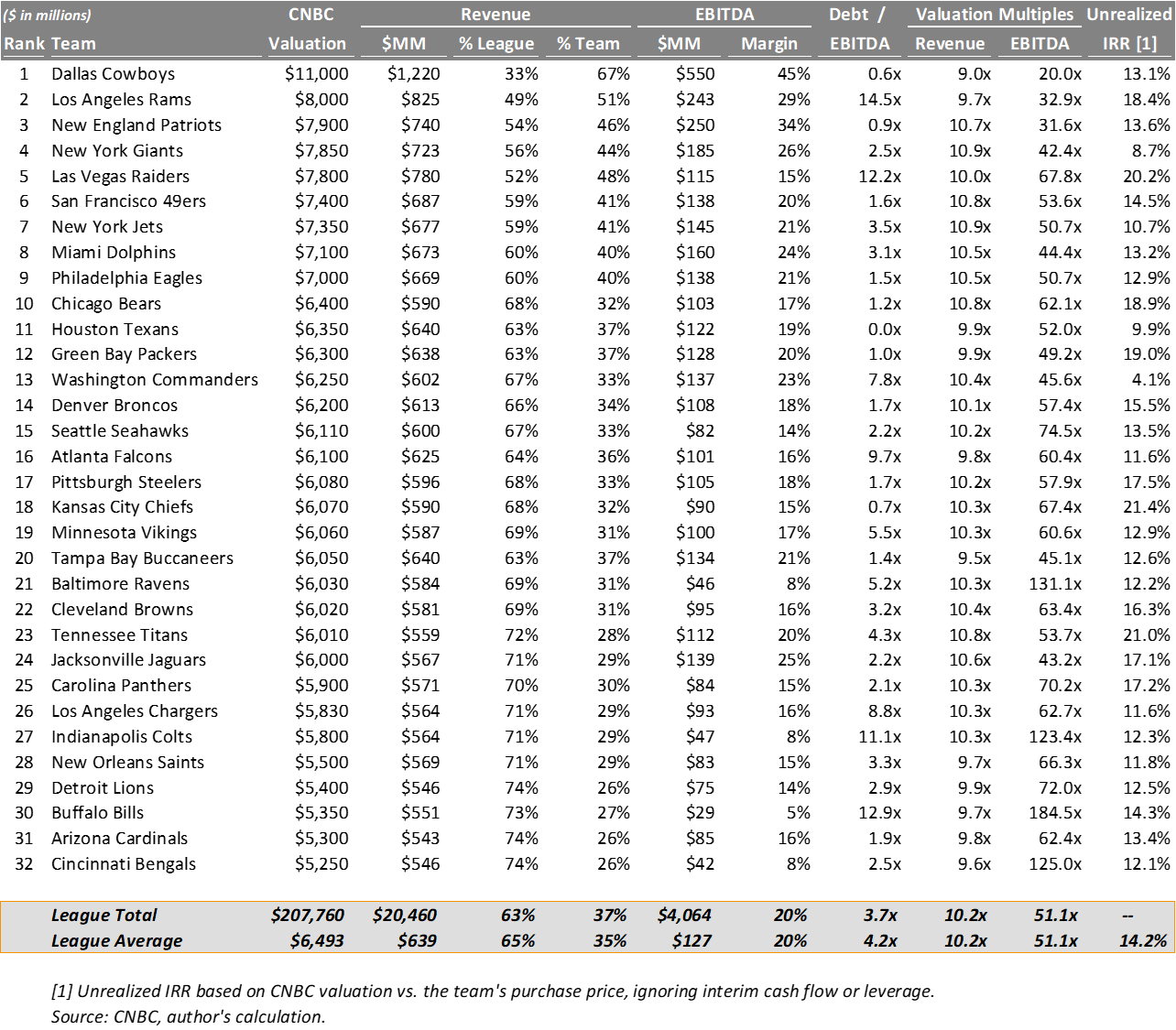

While the remaining league data is privately held, CNBC has compiled estimated revenue, EBITDA and debt figures by team as a part of their inaugural NFL Valuations. Below, I have compiled this data along with my own calculations to paint a financial portrait of the whole league.

The equal sharing of revenue and expenses across the league enables both parity in play and team valuation. With the exception of a few outliers, a majority of the teams in the league have similar financial profiles. The average NFL team earns $127 million in annual EBITDA on 20% margins, with about 4.0x leverage. Meanwhile, the average team is valued at nearly $6.5 billion.

Note, these valuations are based on a simplistic revenue multiple of ~10x based on the most recent Washington Commanders transaction price. But when taken at face value, owners have seen an average mark-to-market appreciation of over 14% annually, when comparing their initial purchase price to the team’s current valuation.

If these were lemonade stands, I might suggest that a 50x EBITDA multiple seems rich, but these assets are unique.

Transaction History

Below is a history of every team’s most recent transaction price, dating back to 1960. Charted on a log scale, we see that purchase prices have grown at a fairly consistent compounding pace over the long-term.

While Jerry Jones earns praise for his $150 million purchase of the Dallas Cowboys in 1989 (today valued at a league-high $11 billion), his purchase was not particularly unique, nor is his implied appreciation based on today’s valuation2. Essentially every owner in the league has seen annual appreciation between 10% - 20% throughout their hold period, regardless of when they bought in. Even looking back to the oldest transaction — the Chicago Bear’s league registration fee of just $100 in 19203— the annual appreciation is still 20%, within the range of more recent returns (albeit over a much longer holding period).

If NFL franchises, regardless of their record or operations, perpetually appreciate 15%, even ignoring cash flows, it is no surprise that they would attract investor attention. But valuations appreciating at twice the revenue growth rate over the past two decades should raise some eyebrows.

Zooming in on the revenue multiple of transactions of the twenty first century, we see that the two most recent deals were in a league of their own.

Over the prior two decades, teams changed hands at ~3x - 5x revenue, but these recent transactions have effectively doubled the price for admission to the owners club. These new high-water marks have effectively doubled valuations across the league, and in doing so, provided half of the “appreciation” for existing owners to date.

Could the introduction of private equity buyers push valuations even higher?

NFLBO

Let’s ignore the current 10% cap on ownerships and pencil out a full buyout model for the average NFL franchise at today’s prices with some basic assumptions.