Down the Drain

#8: Quantitative tightening, the Fed's balance sheet, and liquidity.

Last week, we discussed Quantitative Easing. This week, we discuss Quantitative Tightening.

Quantitative Tightening did not begin this month. It began one year ago. Let me explain…

The Federal Reserve has two tools to implement its monetary policy, one old and one new.

The old tool is interest rate policy. The Fed uses short-term interest rates to encourage or discourage credit creation and money supply.

The new tool is liquidity policy. To save the financial system in 2008, the Fed directly intervened in the US Treasury (“UST”) and Mortgage-Backed Security (“MBS”) markets to stabilize prices and inject much needed liquidity into an over-levered banking sector. The original QE was a wartime measure - the first large scale use of liquidity as a policy tool - but wartime measures have a way of sticking around.

With interest rate policy, the Fed conducts an orchestra, guiding the musicians with its baton. With liquidity policy, the Fed grabs an oboe and plays it with a leaf blower.

Directly influencing public market liquidity is now a key policy tool of the Fed. To create liquidity, the Fed purchases bonds from the public in exchange for newly created dollars (“Quantitative Easing” or “QE”). In the process, the Fed’s balance sheet expands. To reduce liquidity, the Fed allows the bonds it bought to mature without reinvesting the proceeds, removing those dollars from the system (“Quantitative Tightening” or “QT”). The Fed’s balance sheet shrinks.

But the size of the Fed’s balance sheet is not the only factor that influences market liquidity and is insufficient to understand liquidity conditions in practice. Though the Fed has only just begun reducing the size of its balance sheet, market liquidity crested in late 2021 and has been on a sharp decline since, thanks to other critical changes in the Fed’s policies.

Optimistically, the Fed may not be as far behind the curve on taming money growth as many think. Pessimistically, the Fed failed its one previous attempt at liquidity tightening. Now embarrassed and headstrong to tackle rampant inflation, the Fed seems likely to repeat its mistakes.

Breaking Down the Balance Sheet

The Fed’s balance sheet is the total number of US dollars in existence. But knowing where these dollars sit is key to understanding market liquidity in practice.

Let us split the balance sheet into two categories.

The first is dollars that are held by the Fed itself. These include dollars in the federal government’s checking account (the “Treasury General Account” or “TGA”), dollars held in the Fed’s Reverse Repo Facility (“RRP”), and other smaller accounts including those for foreign banks and international organizations1.

The second is dollars held by the public, the Monetary Base, which consists of physical currency as well as cash assets of commercial banks. The Monetary Base and cash assets at commercial banks are far better barometers of liquidity in the financial system than the total size of the balance sheet. If you are a central banker using liquidity as a monetary policy tool, these subcategories are critical.

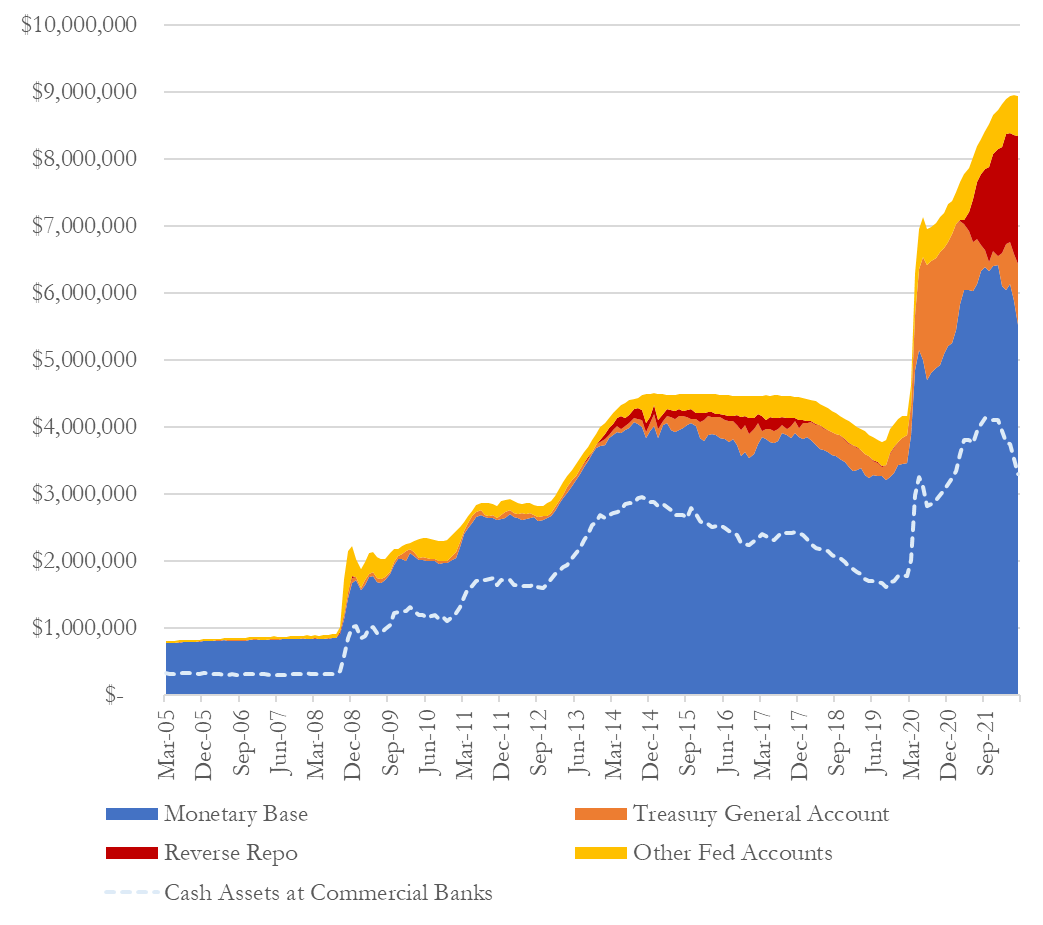

Below is the Fed’s balance sheet broken down into these categories.

While QE and QT expand or contract the total size of the balance sheet, the public dollar liquidity (i.e. Monetary Base) is equally impacted by movements in and out of the Fed’s accounts.

In December 2021, the Fed’s balance sheet stood at $8.7 trillion, of which $6.4 trillion or 74% was held by the public, and $2.3 trillion or 24% was held at the Fed.

Five months later in May 2022, the balance sheet had expanded by $210 billion to a total of $8.9 trillion, yet the total amount held by the public had shrunk to $5.5 trillion or just 62% of the total.

Despite balance sheet expansion, the public dollar liquidity had decreased by $886 billion - the fastest drain of Monetary Base and cash at commercial banks on record.

To understand where we are today and what comes next, consider the following:

Balance Sheet Roll-off (easy)

Treasury General Account (quick and dirty)

The Reverse Repo (the good stuff)

Balance Sheet Roll-off

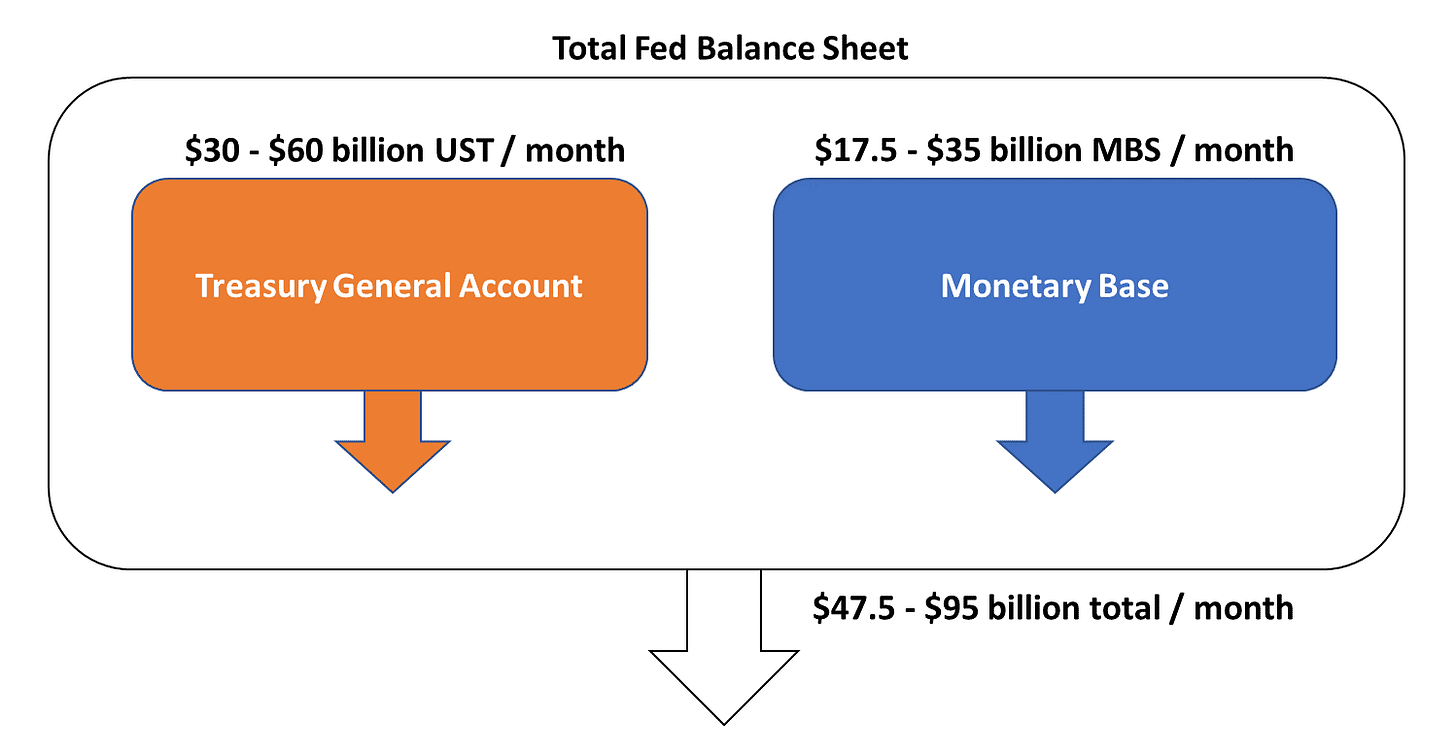

Balance sheet roll-off or “Headline QT” is the simplest to project. Beginning in June 2022, the Fed will allow up to $30 billion UST and $17.5 billion MBS to mature without reinvesting the proceeds. After three months, these figures will double to $60 billion and $35 billion, respectively.

In total $47.5 - $90 billion of liquidity will be drained monthly by debt repayments to the Fed. Where is that money is coming from?

The majority of Headline QT is expiring UST, meaning that the US Treasury will be paying off debt from its own account at the Fed - the Treasury General Account. This will not directly impact public market liquidity. Eventually though, this drain on the TGA will force the Treasury to issue more debt in the future, taking liquidity from the public market in the process.

The MBS roll-off of $17.5 billion per month will drain public market liquidity. Specifically, these funds will originate from homeowners who make their regular interest and principal payments - meaning that commercial bank cash balances will be reduced as well. While any drain on public liquidity is meaningful, the monthly sums currently contemplated are not very large, at least compared to $886 billion of drained liquidity YTD. This MBS roll-off will likely be more impactful on the mortgage market (i.e. increasing mortgage rates) than on dollar liquidity.

Treasury General Account

The balance of the Treasury General Account is largely driven by fiscal policy, though increasingly it has implications for monetary policy and liquidity.

In general, the TGA has a circular flow dynamic with the Monetary Base. It draws in dollars from the public via tax receipts and sends money back to the public by spending. Deficits must also be funded from the public through new debt issuance. Increasing TGA balances means fewer public dollars, and vice versa.

Headline QT will be an incremental drain on TGA funds, forcing the Treasury to raise more debt than would be needed to cover the deficit alone.

Since COVID, the TGA balance has fluctuated by the trillions - something never before seen - with significant implications for market liquidity. In order to fund the COVID stimulus packages, the Treasury needed to pull $1.8 trillion from the public. This feat would not have been possible if the Fed did not preemptively inject trillions of liquidity into the market in March 2020 (the topic of prior writing).

The initial spike in the TGA in early 2020 was offset by bazooka QE and so did not reduce the Monetary Base accordingly. The $1.8 trillion in the TGA was then spent over the course of the next year and half significantly expanding the Monetary Base2.

After drawing down its supply, the Treasury had to replenish the TGA in early 2022. But this time, it had to take dollars from the public through debt issuance without the benefit of QE. Unsurprisingly, UST yields rose dramatically during this period as the market was forced to organically absorb the Treasury’s demand for dollars, without meaningful help from the Fed.

Going forward, the Treasury will have no help from the Fed - rather it will need to fund $30 - $60 billion of Headline QT monthly in addition to whatever deficit it runs. All of this money must come from the Monetary Base - with pressure on UST prices and yields in the process.

The TGA has about $720 billion of dry powder today.

The Reverse Repo

The trouble with liquidity policy, like playing an oboe with a leaf blower3, is that it’s really tough to find the right volume and pitch, particularly if you’ve never played the oboe, and are conducting an orchestra at the same time.

When injecting liquidity via QE, the Fed has little idea how much is too much. At some point, it injects so much cash that short-term interest rates go negative.

The Reverse Repo Facility was a tool that allowed the market to give dollars back to the Fed, rather than buy negative yielding debt. This was an overflow facility that mopped up the excess liquidity. It didn’t pay interest, but no interest is better than negative yield.

The RRP was used from the end of the post-GFC QE cycle in 2013 until the Fed began to raise interest rates and shrink the balance sheet in 2017. As market rates increased along with Fed hikes, the dollars in the RRP flowed back into the market to earn a positive return. It worked as intended.

The RRP came back into use in early 2021 to absorb the flood of liquidity from the TGA’s $1.8 trillion drawdown while keeping short-term rates from going negative.

But then things changed.

On June 16, 2021, at the behest of Money Market Funds (“MMFs”)4, the Fed began paying 5 basis points of interest on the RRP. Uptake exploded.

In my words from December, the decision to pay interest on the RRP upended modern finance. To understand why, consider the incentives of MMFs, which hold over $5.1 trillion in assets and are the largest users of this facility.

Money Market Funds are supposed to be the safest investment funds in existence. Their purpose is to always be redeemable for $1.00, and they are required to invest in ultra high quality, ultra short duration assets like treasury bills and overnight repos. MMFs are not hedge funds. Their objective is not to take risk to maximize profit, but rather to minimize risk and never fail, ever.

The RRP is the best investment for an MMF. It has no duration. It has no counterparty risk. It is truly riskless.

Sure, the alternatives may have almost no risk - but they have some. No risk is better. MMFs don’t construct their portfolio for blue skies but for the worst day you can imagine - and on that day, the US government defaults, clearinghouses fail and companies default on commercial paper. In fact, the more strained liquidity conditions get, the more each of these risks rise - reflexivity in action.

In 2021, MMFs dumped over $600 billion in US Treasuries, and pulled $300 billion from the public repo market in favor of the Fed’s RRP. At year end, RRP made up 40% of Government MMF and 33% of total MMF holdings from zero at the start of the year5.

When an MMF chooses to allocate dollars to the RRP, it drains public market liquidity. Given the incentives of MMFs, this drain will continue.

Making matters much worse is the Fed’s decision to raise the interest rate on the RRP along with each rate hike. By doing so, the Fed creates a massive economic incentive to allocate to the RRP, beyond the facility's attractive risk characteristics. This week’s rate hike increased the RRP rate from 80bps to 155bps. With the 1-month UST yielding just over 105bps, there is now 50bps of incentive to sell UST and allocate to the RRP.

The RRP will not drain with rate hikes and QT as it did in the prior tightening cycle. Rather, RRP uptake will only accelerate with every incremental rate hike, draining liquidity in the process.

This is a disaster in the making. Not only has the Fed fundamentally rewired funding markets by providing a riskless asset that drains public market liquidity, it also tied its liquidity policy to its interest rate policy without an understanding of the implications. The Fed is aware that it is draining liquidity via the RRP - it say it is working as planned. I remain highly skeptical.

Unlike Headline QT in which the Fed determines a gradual, consistent schedule of roll-off, tightening through the RRP is a free-for-all. How much RRP uptake is the “right” amount? You don’t know and neither does the Fed. All they know is how much decides to show up.

Today, nearly 25% of all dollars ever printed sit in the RRP.

Putting it Together

Officially, Quantitative Tightening may have just started, but the true public dollar liquidity has already tightened meaningfully. The Monetary Base and cash at commercial banks peaked in 2021 and has been on a steep decline since.

Tightening has been led by the exploding volumes in the RRP. The Fed’s decision to continue to hike RRP interest rates ensures this facility will continue to reduce the Monetary Base at a rapid pace. Headline QT will drain liquidity as well but in a controlled and gradual manner. Fluctuations in the TGA will add further volatility in both directions.

Contracting liquidity is the reason behind increased UST yields, skyrocketing mortgage rates and a falling stock market.

So what?

Well, the Fed is 0 - 1 so far in successfully executing a tightening cycle.

The previous tightening attempt only included a gradual balance sheet run-off. Still, the Fed drained a third of the cash out of the banking system in about 18 months. Banks’ leverage and liquidity metrics quickly reached their regulatory limits, which are much more stringent in the post-GFC era. Eventually, the public repo market broke in September 2019 and required the Fed to intervene with a new round of QE to reintroduce liquidity.

Today’s leverage and liquidity metrics do not look as stretched as 2019 yet, but the drain of liquidity is much more rapid. The new RRP vacuum plus a more aggressive roll-off schedule ensure that liquidity will continue to drain at a faster rate than the prior cycle.

The Fed has shown little ability to understand the “right” level of liquidity, rather it reacts to problems after they arise. Now, under huge pressure to tackle inflation, it seems destined to overtighten until something breaks.

Is this a good thing?

On the one hand, the Fed is perhaps not as far behind the curve as many perceive. Various measures of money growth have all decelerated in recent months, and financial markets have experienced meaningful losses. Consumer price inflation lags monetary policy, so recent CPI prints probably don’t incorporate these new liquidity conditions.

On the other, inflation will likely persist regardless due to the massive step-change in money supply in 2020. The optimal solution would be a redo button. But a crash landing is not a redo button and could make matters worse.

Ultimately, my biggest concern is that the Fed continues to employ powerful tools that they cannot wield. It devises new inventions to solve yesterday’s problems and creates the problems of tomorrow in the process.

Maybe they should stop trying. It’s time to retire liquidity policy altogether.

As these other account balances have remained stable over time, we will not focus on them in this analysis.

The drawdown of the TGA to low levels was due to the debt ceiling standoff in late 2021. The ceiling prevented the Treasury from issuing the debt it normally would and forced it to draw down the TGA instead.

Or playing the cello with a hacksaw. Or drilling a cavity with jackhammer. Pick your metaphor.

There’s a post that can be written just on MMFs. The short story is that these funds are critical to financial plumbing and things go really bad if they “break the buck” as some did in 2008. The Fed has always been very wary of the risk posed by MMF blowups. Ironically, with short-term rates at zero, MMFs warned they would break the buck because they had no interest revenue to offset their expenses. This was the driving force that caused the Fed to begin paying interest on the RRP.

The reporting on MMF holdings lags substantially, so the latest data available from the Fed is as of January 2022. If we had data through today, these numbers would be meaningfully higher.

My understanding of all of this is so many levels below you. I am an engineer by trade who graduated in 2010. The job market was non existent. As such, I have always been interested in the GFC, what caused it and how we “got out of it”. I saw your posts after the Michael burry retweet and haven’t stopped following. I have more or less come to the conclusion that we did not recover, we simply kicked the can down the road and are being led through a jungle as the fed uses a dull knife and a broken compass to forge a new path through thick foliage.

Your posts really are much appreciated, but also terrifying.

Thanks again TLBS and keep it up

"With liquidity policy, the Fed grabs an oboe and plays it with a leaf blower."

Great article, very informative. Well it was after I stopped to wipe the tears from my eyes after laughing so hard at this line.

Right now we're all at the Indy 500 and watching the cars races around, but it's just a matter of time until there's a crash. The only question is where will it happen on the track and what will be the cause.