Boom to Bust

#39: On Rates and Affordability in the U.S. Housing Market.

Last summer, we assessed the state of the U.S. housing market in The Housing Bubble. We concluded:

Six short months have reversed fourteen years of declining mortgage rates and the purchasing power they provided. The result is a neck-snapping whiplash in buying power and fair values…

Rates giveth and taketh away. Now we sit on a significantly overvalued housing market, due for a price correction so long as mortgage rates hold up at current levels.

This wasn’t a bold or unique prediction, rather simple arithmetic based on the relationship between interest rates and buyer purchasing power. Now, using the Case-Shiller housing index1, a high-quality but delayed dataset, we can pinpoint June 2022 as the definitive peak of U.S. housing prices.

Today, let’s review the latest price data and the outlook from here.

The Peak

For the first time since 2011, housing prices are falling in nominal terms. Nationwide, housing prices fell 2.4% from June 2022 to October 2022 (the most recent data available).

Perhaps more notable than the absolute level of decline has been the speed of the reversal. Unlike the mid-2000s bubble which included a two-year plateau from 2005 - 2007, the near vertical price increases since the beginning of the COVID pandemic have immediately given way to declines2.

While price cuts have been universal nationwide, the degree of correction has been highly regional. All of the 20 tracked metro areas show outright declines but West Coast cities have led the market downwards. Tech hubs, Seattle and San Francisco, stand out with double digit declines - perhaps tracking the rise and fall in the value of the stock options of their residents. Meanwhile, price reductions on the East Coast and Midwest have been modest so far.

Still, these losses are dwarfed by the gains of the pandemic - the average U.S. house remains 39% more valuable compared to January 2020, or 22% higher in inflation-adjusted terms.

Broken down by geography, the gains are universal, but are the greatest in sunny snowbird destinations like Phoenix, Tampa and Miami.

Yet, with average mortgage rates today hovering above 6.0% - the highest level since 2008 and double the rate during the pandemic - is there more pain on the way?

Affordability & Fair Value

Merely considering nominal prices ignores critical variables necessary to understand housing affordability over time. To better predict the direction of housing prices from here, we must normalize for changes in nominal incomes and mortgage rates.

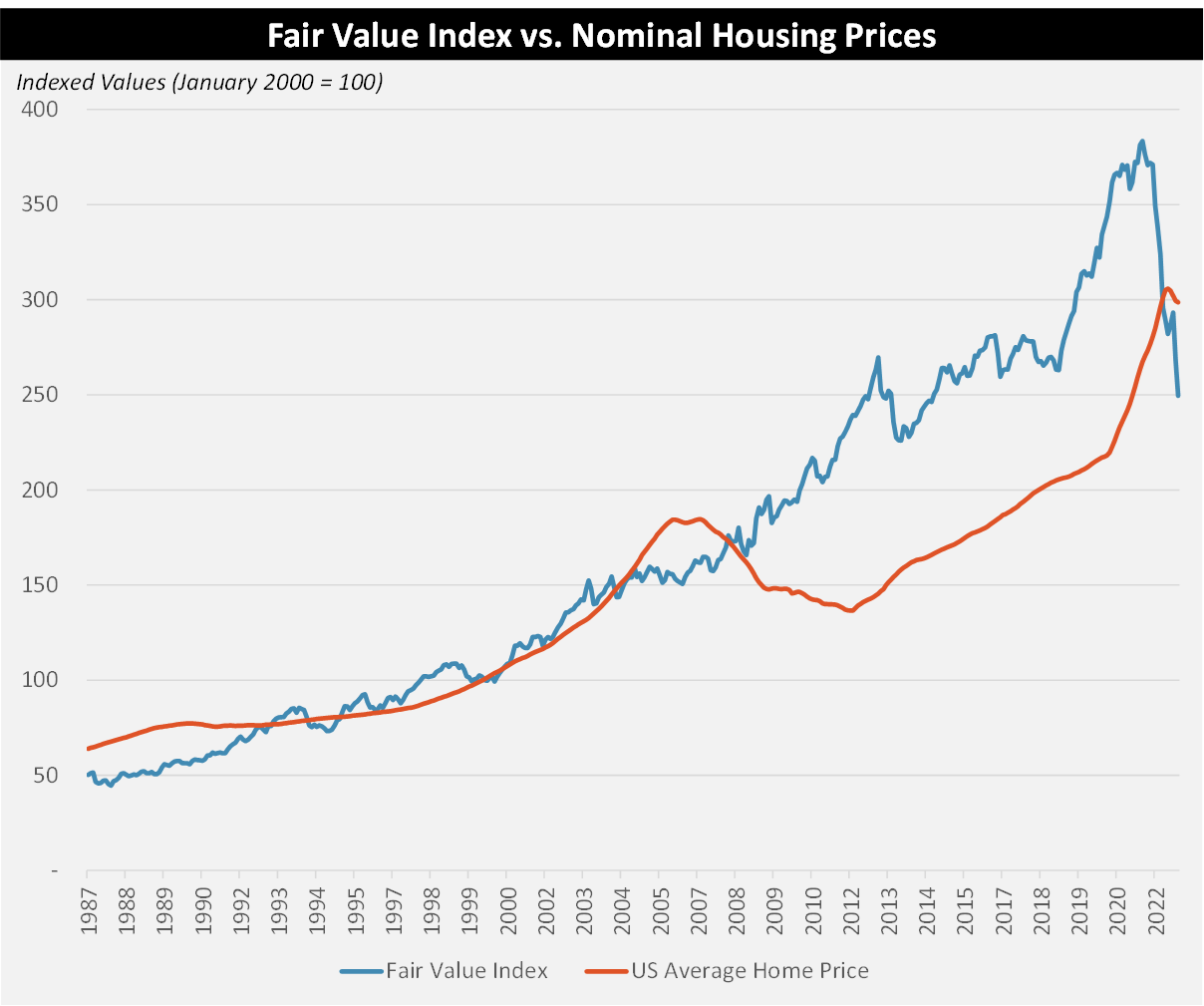

Below in blue we have constructed a “fair value” index which shows the expected change in home prices based on growth in disposable income per capita3 and the buying power implied by the 30-year mortgage rate. Comparatively, we show actual home prices in red. Both series are indexed to January 2000 as a baseline.

To the extent that actual home prices (red) are greater than the fair value index (blue), one could argue that housing is relatively expensive, and vice versa4. While the two series tracked relatively closely throughout 1990s, actual home prices accelerated past affordability in 2004, at the beginning of the last housing bubble.

But the biggest divergence didn’t occur during the bubble, but rather in the aftermath, as actual housing prices crashed well below their expected fair values5.

To use a concrete example - nationwide home prices were roughly flat from 2003 to 2013. Yet, during that ten-year period, disposable income per capita grew by 36% and mortgage rates fell from ~5.5% to ~3.5%. On a relative basis, homes were far more affordable in 2013 than in 2003. This divergence persisted throughout the past decade.

In this context, the price run during the pandemic was highly rational. Fair values actually began accelerating higher before COVID, as the famous Powell Pivot in late 2018 resulted in mortgage rates falling 100bps through 2019. Then, the combination of zero-rates and nominal income growth during the pandemic increased buying power even further. The huge increases in housing prices during the pandemic closely mirrored rising relative affordability, on a lagging basis.

Bidding wars don’t happen unless many buyers are qualified to purchase a given home. The COVID housing “bubble” was not due to irrational animal spirits, but rather due to a dramatic increase in buying power - a direct and intended result of monetary policy.

So too is the “crash”.

In just one year, the Fed’s hiking cycle has pushed mortgages rates to the highest level since 2008, reversing over a decade of rate-driven gains in purchasing power. The magnitude of increase is greater than any period since the early 1980s. The impact is even greater considering that it comes from a historically low base.

The result is a dramatic whiplash in affordability. In April 2022, the fair value index fell below nominal prices for the first time since 2008. By October 2022 nominal prices exceeded fair values by 20% - comparable to the peak of the mid-2000s bubble6.

In other words, even as nominal prices started to fall, the rise in mortgage rates in late 2022 caused housing to be even less affordable throughout the year. This bodes ominously for the future.

The Outlook

Since our last update, housing prices peaked and have begun to fall, consistent with our expectation. So far, the West Coast bearing the brunt of the correction, though the wave may be heading east.

However, despite these early price declines, the housing market has become even less affordable than it was last summer due to the Fed’s consecutive 75bps rate hikes. The recent easing of financial conditions7 may provide some short-term reprieve, but prices will continue their downward trend absent a reversal in the direction of monetary policy. More recent data such as rapidly declining monthly sales and new building permits, or rising contract cancellations by homebuyers confirm this view.

Fortunately, there is far less systemic risk than the last go-around, even in a protracted down-market. Folks didn’t buy houses they can’t afford - it’s just that new buyers can no longer afford those same prices. While this could prove problematic for forced sellers with limited equity value, most pandemic buyers remain locked into fixed rate payments. The vast majority of homeowners have much greater home equity today than they had before the pandemic. Delinquencies remain historically low and banks are far better capitalized to withstand losses if they occur.

Even still, housing prices are likely to fall further. The great pandemic boom has peaked - now we wait out the bust.

If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, please subscribe, hit “like”, and tell a friend! Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

As always, thank you for reading.

-TLBS

The Case Shiller index only looks at repeat sales of existing single-family homes, so this index doesn’t capture multi-unit buildings or new sales. The complete methodology is described here.

While this reversal looks more dramatic on a chart, it’s better that prices revert quickly, as only a small number of homes actually transacted at peak values.

In our previous post, The Housing Bubble, we made a different “fair value” index which adjusted for CPI inflation and mortgage rates. However, as one reader noted, simply using CPI ignores the gains in real income. This is an important distinction and so we have adjusted the methodology for this post. Finally, for disposable income per capita, we have removed transfer payments (i.e., fiscal stimulus) during the pandemic.

Any index we create will be imperfect. This fair value only suggests what the average person could pay for a house based on these two factors. It doesn’t consider other important variables such as the supply and demand of housing units, the relative weighting of housing expenditure as a percent of income, or household debt levels. Further, these “fair values” are relative to a given baseline - January 2000.

Again, there are plenty of reasons that may help explain this divergence. The single-family building spree during mid-2000s and subsequent forecloses left a glut of supply. Individuals were focused on de-levering after the GFC, rather than taking on new debt. Psychology must have also played a factor - speculators had been burned and housing went out of style. Remember that in the years after the dot-com bubble, Microsoft traded at 8x P/E.

Applying today’s 6.13% rate to October 2022 price data implies a 12% premium.

Even as the Fed has continued hiking rates, yields on longer-term treasuries have come down substantially bringing mortgage rates down from their peaks in October.

Great analysis. As long as we have a strong labor market, I don't think housing prices will go down that much. We have a structural supply shortage in housing in the US.

What might trigger the next leg down is a worsening of the labor market or higher interest rates if inflation creeps back up. If we're in the midst of a commodity supercycle as many are predicting, the current downtrend in inflation will not last. If/when oil goes back up to $100 a barrel, the fed will be forced to keep rates higher for longer.

Thanks for this article Mr. Bear! As an spanish, I'm looking at this in a very similar way in my country. Prices still high due to the high demand that cities have. Also, the gross of the properties are in boomers power, younger generations cant afford to live with more than 40% of their salaries into mortgage (very few takes this option) nor renting. So let's see once this get's more even unsustainable with the pensions ponzi fraud (you should do one article about this, would be funny :)

Regards TLBS!