Barbarian at the Gate: The Twitter Buyout

#31: Valuation, Sources & Uses, Buyout Model, and Sensitivities

Last week, I wrote about Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter in Turkey, Twitter and Tesla. In response to the qualitative thoughts, a couple people gently asked me for some real work on the topic.

I agree. Last’s week’s review was somewhat half-assed (in my words) and I appreciate readers calling this out. After all, I’ve previously written about the pitfalls of narratives in lieu of rigorous analysis. So here it is - a detailed review of the Twitter Buyout.

Let’s jump right in.

Financial Overview

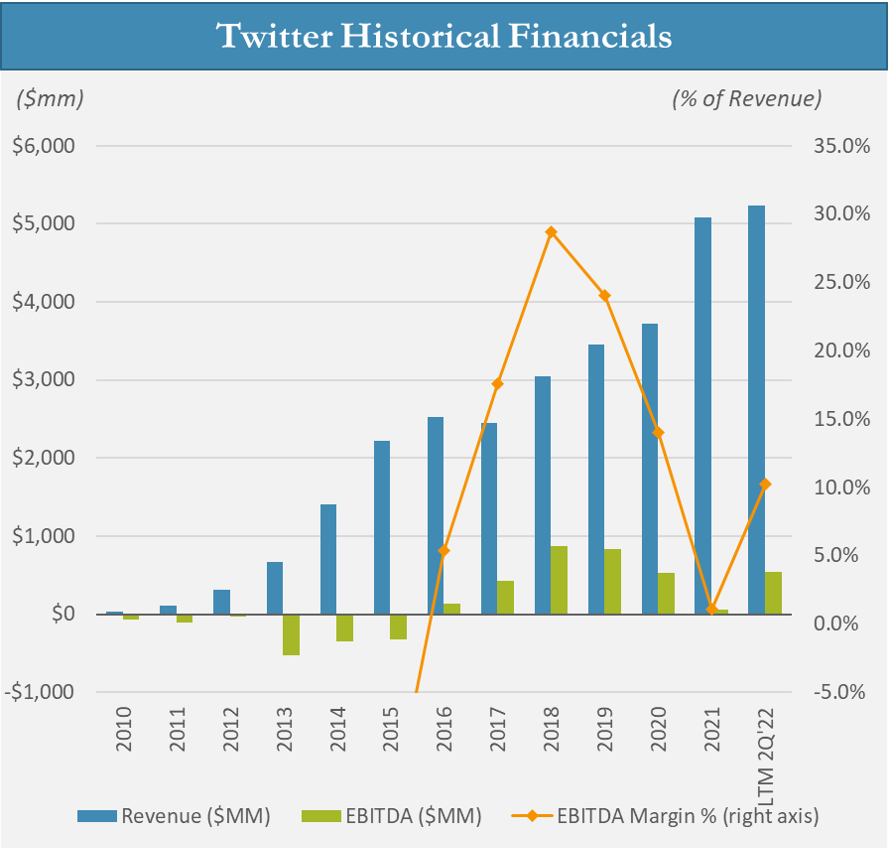

First, let’s look at Twitter’s results1 going back to the beginning of reported financials in 2010.

Revenue: Revenue grew from $28 million in 2010 to $5,228 million as of 2Q 2022, a 57% compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) over the period. While much of this growth came from a small base, Twitter has maintained strong topline growth in recent years, growing at 17% CAGR since 2018.

EBITDA: After losing money (on an EBITDA basis) for the first five years, Twitter posted its first positive results in 2016. By 2018 the company posted annual EBITDA of $874 million, at a 29% EBITDA margin. But since 2018, the company has seen a collapse in margins. Costs have outpaced revenue leading to shrinking profitability over the past several years.

In short, the top line growth remains strong, growing in the mid-teens annually, consistent with its growth in underlying user base as measured by Monetizable Daily Active Users (mDAU) which has grown at a 19% CAGR since 2018.

Rather, Twitter’s problem has been rapidly rising costs. The collapse in margins is startling, and has occurred at every level of the income statement - costs of goods sold (COGS), sales and marketing (S&M), research and development (R&D) expense, and general and administrative (G&A) - even off the income statement in capital expenditure.

If one was confident that they could cut costs without sacrificing revenue, Twitter seems like a reasonable buyout candidate. Applying the 29% EBITDA margins achieved in 2018 to its LTM revenue of $5.2 billion would yield $1.5 billion in EBITDA today - three times higher than its actual LTM EBITDA. (Though as noted last week, cost savings are often easier to achieve in Excel than in real life).

Purchase Price, Sources & Uses

Now, let's turn to the buyout. Below is an estimated purchase price, valuation, and sources and uses (S&U) based on the $54.20 acquisition price per share, and the financing per the debt commitment papers2.

The purchase price implies an Equity Value of $41.4 billion and an Enterprise Value of $40.5 billion after backing off the existing financial debt and cash balance at the company. Assuming no company cash was used to finance the acquisition and all existing debt was repaid at closing, the total funding need stands at $47 billion, made up of $34.5 billion of equity and $12.5 of acquisition debt (including a $0.5 billion undrawn revolver).

How expensive is this acquisition? Well that all depends on how you measure it.

Using an LTM EBITDA of $537 million implies an EV/EBITDA acquisition multiple of over 75x - which is… really expensive.

But the whole reason you are buying the company in the first place is because you think the cost structure is bloated. If you assume you can quickly achieve cost savings (by, say, firing half your headcount in the first week), then the multiple begins to look much more reasonable.

Using an optimistic 2023 Pro Forma EBITDA (to be discussed herein), one could argue the deal implies just a 22.5x forward EBITDA multiple, a far more reasonable price, and incidentally right on top of the average forward trading multiple during Twitter’s time as a public company.

If you prefer to ignore costs entirely, the transaction is at a 7.8x LTM revenue multiple.

The other thing that jumps off the page is the cost of this financing. The acquisition debt ranges from Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) plus 475bps - 1000bps initially, and the $6 billion of bridge loan facilities include a 50bp interest step-up quarterly (up to unspecified cap) if the loans are not taken out with other financing.

Making matters worse, SOFR jumped from 0.30% when the deal was signed in April, to 3.05% by the time of closing in October, adding 2.75% of interest cost3 to $12.5 billion of debt. The day-one weighted average cost of debt is 9.5%, with an annual debt service cost of over $1.2 billion including mandatory amortization. It gets more expensive quickly, as the rate escalators kick in.

But considering opening net leverage (net debt / LTM EBITDA) of nearly 12.0x, this cost of debt shouldn’t be too surprising. With over $6 billion of cash on hand, there is no immediate default risk but this company is officially up to its eyeballs in debt.

It’s an expensive headline valuation that’s predicated off the assumption of meaningful cost savings, with maximum, expensive leverage. A true LBO, indeed.

Buyout Model

I don’t know whether Musk had any detailed projections or assumptions when he decided to buy the company. But I am highly confident that before the deal was signed in April, a handful of junior bankers at Morgan Stanley put together a giant fancy model demonstrating (i) that the acquisition financing can be serviced, and (ii) that the buyers will make money on the transaction.

Here is my grossly simplified version of that “underwriting case”, that I bet is not too far off. Here are the key assumptions (blue font in the model):

15% annual revenue growth, in-line with historical trend. Note: at the time of underwriting, I doubt anyone assumed that advertisers would flee on day one. We will discuss this point later.

30% EBITDA margins based on headcount reduction, and in-line with 2018 levels

Reduction in capital expenditures to 12% of revenue, which is consistent with company’s relative capex spend during its growth period in 2015 - 2018

A five-year hold period, with an “exit” in 20274 based on a 23x forward EV/EBITDA multiple, which was Twitter’s average forward trading multiple from 2015 - 2022.

Acquisition financing stays in place through the hold period

Under these rudimentary assumptions, the underwriting case implies equity returns of 16.8% Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and a 2.3x Multiple of Invested Capital (MOIC). I wouldn’t call that a home-run, but it’s probably not far off from where many private equity deals get underwritten these days.

Using a simplified cash flow, which doesn’t account for changes in working capital or other extraordinary expenses, the company can almost service its massive debt burden from organic cash flow, with only a small drawdown in the $6 billion of cash on hand to cover the shortfall. The company de-levers substantially to 1.8x net debt / EBITDA by 2027.

Of course, this all hinges on an aggressive turnaround plan - that users and revenue continue to grow (doubling over the projection period), and more importantly, that costs can be axed. Most of the value creation relies on cost savings.

So far, thing have not gone entirely to plan.

Revenue and Cost Sensitivities

Just a month into the deal, two things have happened.

First, many advertisers have cut or eliminated their ad spend on Twitter since the takeover. Media Matters (a politically progressive group) reports that half of the company’s advertisers have stopped advertising. Washington Post reports that a third of its top advertisers have cut spend entirely in the past two weeks. Musk himself has lashed out at Apple for cutting spend. While I suspect some of this reporting may be exaggerated and that a temporary pause may not prove permanent, it’s clear that Twitter has taken a big revenue hit in the opening days of Musk’s ownership. Directionally, this is bad.

Second, a substantial majority of the workforce has left the company, either voluntarily or involuntarily. Bloomberg reports that only 2,750 employees remain today compared to over 7,000 pre-acquisition, a reduction of over 60% with potentially more to go. Personnel expenses contribute meaningfully to Twitter’s cost of goods sold (COGS), and make up a majority of its operating expenses (S&M, R&D and G&A). Ignoring the operational risk of such a massive, haphazard reduction in headcount, this will dramatically reduce costs. Directionally, this is good (for cash flow).

But this also mean that you can throw our “underwriting case” out the window. Both revenues and costs are being reset to some new, unknown level, and not necessarily driven by our margin framework.

Let’s instead look at basic sensitivity, assuming a haircut to both revenue and operating expenses independently in year-one, followed by 15% growth in each throughout the remaining hold period. All other assumptions remain the same.

Again, using monkey numbers, we see that that a permanent 50% drop in advertising revenue would be devastating, beyond the possibility of cost savings to restore5. At some point, there are no more heads to cut, and the non-personnel expenses like servers and infrastructure are much harder to reduce.

Alternatively, if the advertiser strike proves to be a knee-jerk reaction, the upside of a leaner cost structure is significant.

Stakes are high.

Relative Value & The Musk Effect

To this point, we’ve focused on Twitter as a standalone buyout, but a key point in my commentary last week was around the strategic rationale for Musk personally. Given that Musk has funded the transaction by selling shares of Tesla, his perspective should be that of relative value.

We can already begin to quantify the impact. Musk sold Tesla over the past year at a weighted average price of $287 on a post-split basis, or $229 after capital gains tax. Tesla today trades at just $194, or a 15% discount to his after-tax proceeds. These forgone losses effectively lower his cost basis in Twitter by that same factor, enough to boost returns by ~4% or 0.3x MOIC in the underwriting case. Not to mention, Musk’s cost basis is actually lower than the math we’ve shown here, since he acquired a 10% of the common equity well below the $54.20 takeout price.

Or, ignore dollar values entirely. From a portfolio perspective, Musk has managed to acquire most of the equity of one of the largest social media platforms while giving up a relatively small percentage of his ownership of Tesla. At the very minimum that is valuable diversification.

But Musk also brings volatility in both directions.

His “mercurial persona” and “outspokenness” has cost his new company hundreds of millions in advertising dollars just days into his acquisition. It’s also possible that his ruthless job cuts may backfire from an operational perspective.

But, if he does turn the company around and eventually seeks to take it public again, we should probably assume a “Musk premium” in multiple, that may result in far higher valuation that what we could expect based purely on historical comparisons.

Conclusions

The Twitter buyout is a very high-risk transaction. Success is conditioned on a meaningful business turnaround, with high-stakes leverage, and a high volatility CEO. A profitable outcome is far from assured, but not out of the realm of possibility.

I continue to see the rationale for the acquisition (while acknowledging its risk), particularly from Musk’s personal portfolio perspective, and believe that the purchase price may not prove frothy as many believe.

Finally, while this piece has focused on Twitter’s financials, there is a qualitative aspect of value that is missed. Twitter, as an increasingly essential platform for the exchange of information. It is a social network, PR Newswire, and marketing platform all rolled into one. Controlling such a platform is valuable in a way that is hard to quantify.

Or, it may all go up in smoke.

Whatever the outcome, it will be a fun one to watch.

As always, thank you for reading. If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, tell a friend! And please, let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

-TLBS

All revenue figures, and EBITDA prior to 2015 are from S&P Capital IQ. From 2015 - 2022, EBITDA figures are based on the Company’s reported “Adjusted EBITDA”, but excluding the add-back for stock-based compensation.

While the initial debt commitment envisioned a $12.5 billion margin loan on Musk’s Tesla shares, this component was dropped by the final deal. For our purposes, we will use the full common shares outstanding to determine valuations, despite the fact that Musk had already acquired around 10% of the shares outstanding at a lower price prior to the acquisition.

Assuming there were no interest rate swaps or other hedges put in place at the time of signing.

Practically speaking, the “exit” would likely be taking Twitter public again in an IPO. For the purposes of modeling returns, we will assume that all of the equity is sold at this IPO valuation, though of course that would not be the case in practice.

It’s also possible that the headcount reductions have been driven in part by the hit to revenue, and that they would not have been so extreme or abrupt otherwise.

Thanks for the deeper dive, Bear. Much respect for holding your word too!

This is great work… now what does it look like if insiders received $54.20 per share on a company that was failing and knew it was failing? What would it look like if Tesla’s primary investor was over leveraged and had $6B invested in a company that was about to go belly up before Tesla’s CEO bought it?