A Solution for QT

#47: QT has hit a brick wall. Here's how to fix it.

Wednesday’s highly anticipated Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) was a dud. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of the speech and press conference focused on interest rates - long considered the Fed’s primary monetary policy tool. Relatively little attention was paid to balance sheet policy - Quantitative Easing (QE) and Quantitative Tightening (QT).

We need to stop talking about interest rates and start talking about balance sheet policy. Interest rates are no longer the primary mechanism for monetary policy.

QE - not interest rates - was the primary driver of money growth since the pandemic. Organic credit expansion has played a relatively minor role.

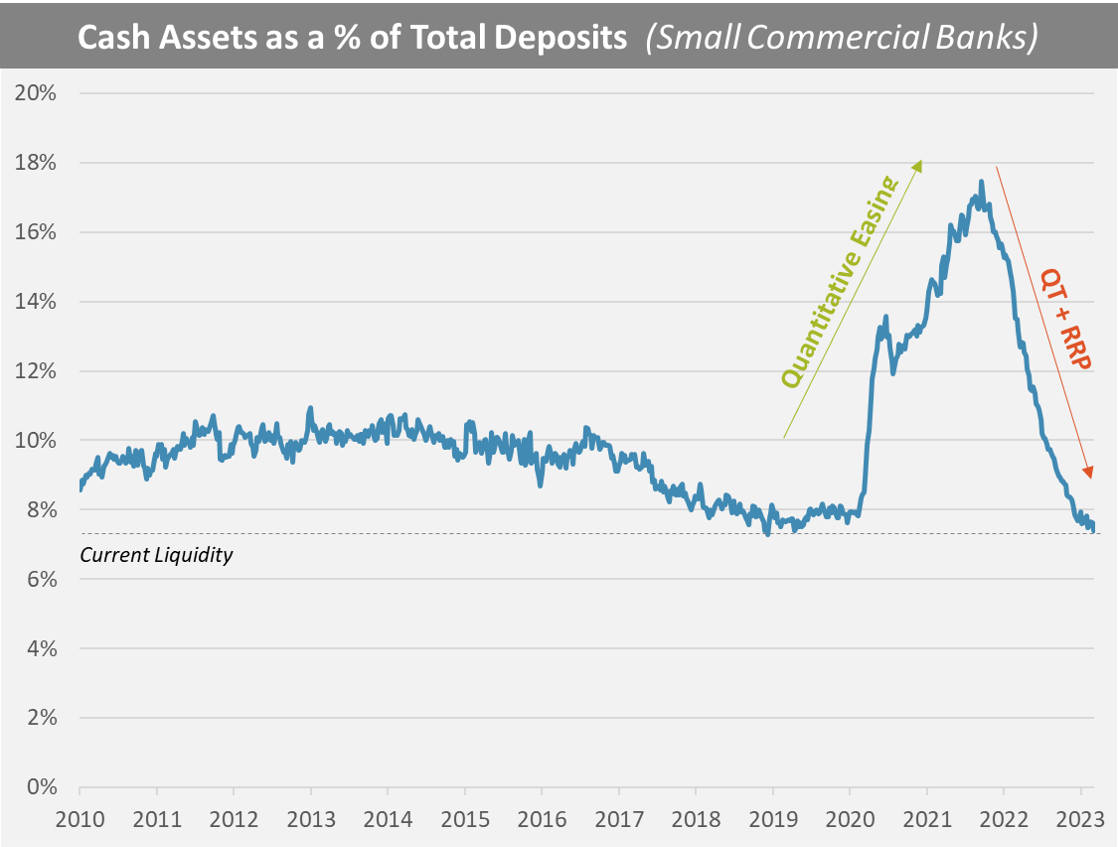

QT - not interest rates - is now the primary driver of current liquidity stress in the banking sector.

Until the problems with QT are addressed, there will be more collateral damage. We propose a solution: “Operation Squeeze”…

Credit, QE and Money Growth

You may have heard that commercial banks “print money” by lending. At best, this an imprecise abstraction.

Commercial banks can’t print base money - i.e. actual dollars. Instead, commercial banks can increase the quantity of bank deposits and the money supply by writing loans. The extent to which banks can stretch base money into money supply is influenced by a number of factors including bank regulation, demand for credit, the price of credit, and underwriting standards.

Money supply - primarily consisting of bank deposits - forms the inner core of liquidity for the broader financial markets and real economies. The purchasing power of all non-bank entities is determined by the bank deposits they hold. Therefore, the quantity of bank deposits and money supply are critical in overall economic growth, financial asset pricing, and the prices of goods and services (inflation).

Up until the 2008, bank lending created most bank deposits. As the graph below demonstrates, total bank deposits closely mirrored loan growth up until the GFC. In this system, interest rates help determine the rate of money supply growth and inflation by changing the price of credit, and explain why interest rate policy has been the primary lever of monetary policy historically.

However, QE introduced a new form of direct money supply growth, dictated by central banks. Today, the growth or contraction of bank deposits is driven both by organic credit expansion as well as the QE/QT policy decisions of the Federal Reserve. Looking at either in isolation will miss the big picture1.

Since 2008, about half of the growth of money supply in the U.S. has been attributable to organic credit expansion underwritten by commercial banks and half has been injected via QE. Since the onset of the COVID pandemic, QE has driven the vast majority of the increase in money supply. Organic credit expansion has been a relatively minor factor2.

Now, those processes are working in reverse. Even as commercial lending has turned positive over the past year, it has been more than offset by QT. Today, money supply and bank deposits are shrinking3 due to the tightening of the Federal Reserve.

Credit expansion was not responsible for the unprecedented explosion in money supply and inflation - this was achieved by edict via QE4. Therefore, the insistence that higher interest rates are required to fight ongoing inflation seems to ignore the elephant in the room5.

Unlike pre-2008 analogs, our ongoing inflation problem is not due to the current rate of money expansion - money supply is shrinking today. Instead, whatever sticky inflation we are still dealing with is more likely due to the lagging effect of the excessive step-change increase in money of the prior two years.

Rather than acknowledge its direct role in money expansion (and now contraction), the Federal Reserve would prefer to blame private sector lending6 for feeding inflation. Ironically, if higher rates cause organic credit to contract (which could occur over the coming year), it may force the Fed back into outright QE in order to stabilize the already shrinking money supply.

QT, Bank Reserves and Liquidity

You may have heard that higher interest rates on Treasury Bills (T-bills) are causing deposits to flee banks. At best, this is an imprecise abstraction. Absent QT and the Reverse Repo facility (RRP), interest rates on T-bills would have no effect on aggregate bank liquidity.

Treasury Bills do not “hold” cash. T-bills are exchanged for cash - cash moves from buyer to seller7. If a T-bill is purchased in the secondary market, cash moves from the buyer’s bank to the seller’s bank. If a T-bill is purchased directly from the Treasury in the primary market, then cash will leave a bank and enter the Treasury General Account at the Fed. But even then, those dollars will eventually return to banks through the Treasuries outlays.

The net effect of the Treasury flows on bank liquidity is determined by the total TGA balance - which includes taxes receipts and government spending along with debt issuance and maturity. Ironically, the TGA has been shrinking since May 2022, which has actually added to bank liquidity8.

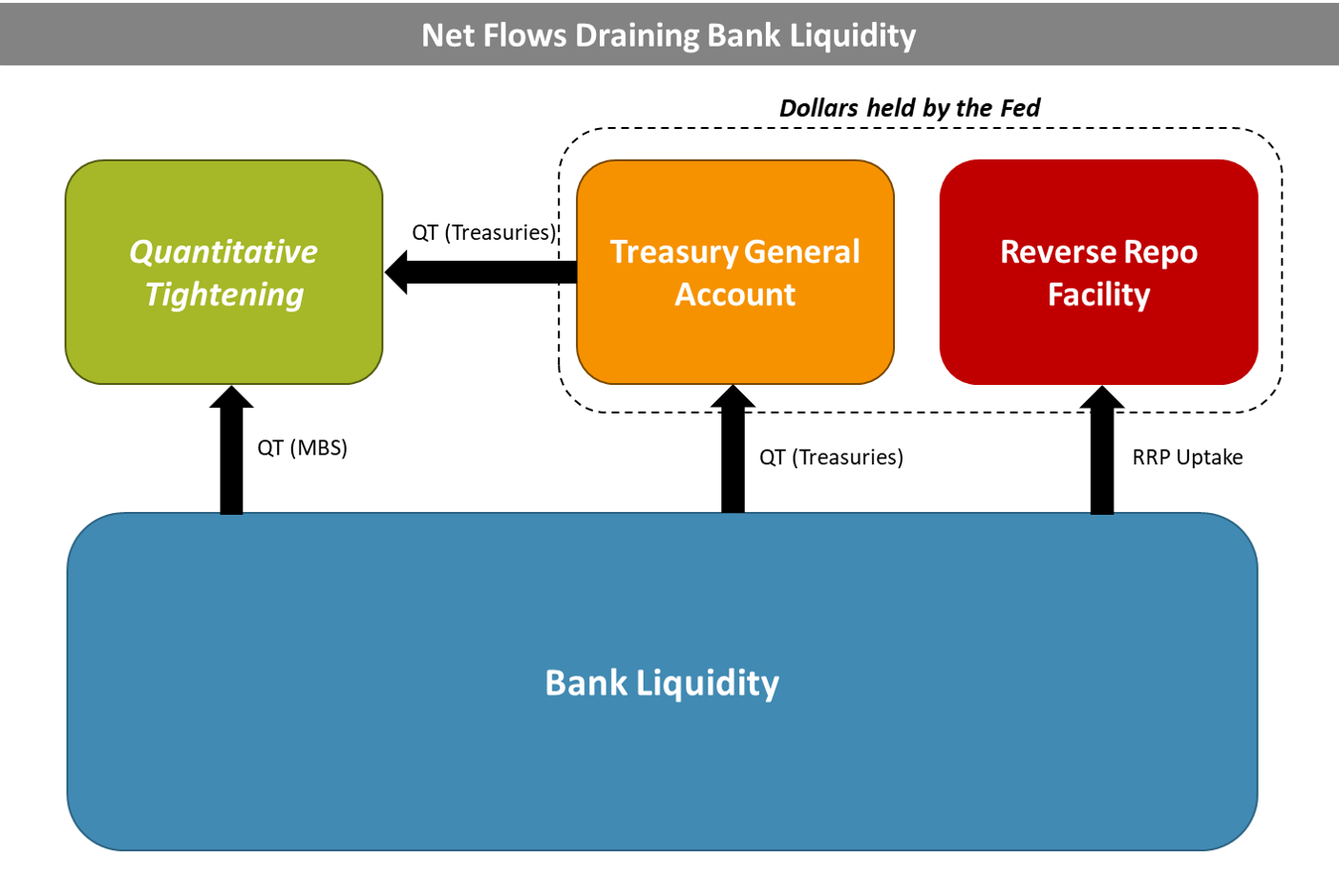

Instead, cash is fleeing the bank system due to QT and the RRP, as described last week.

Certainly, higher rates have created losses in bank portfolios and eroded capital balances, but the primary problem is a lack of liquidity. The combination of balance sheet reduction and flows to the Reverse Repo facility caused a dramatic decline in cash balances, particularly at smaller U.S. banks.

Silicon Valley Bank was the first to fall because of uniquely poor management of its balance sheet, but liquidity stress more broadly is a result of the Fed’s balance sheet policy and predated the recent failures. SVB’s failure merely puts more stress on similarly positioned banks who now must also contend with deposit outflows to competitors.

The Federal Reserve's response to the bank crisis has been to create new emergency lending facilities to improve liquidity. Between new and existing facilities, the Fed has injected $392 billion into the banking sector in the past two weeks - highlighting the severity of liquidity shortage at hand.

Ironically, the Fed seems to have no interest in seriously engaging with the root cause of liquidity drain. Instead, the Fed is content to let QT continue to eat away at bank cash and not address the sticky RRP which puts over two trillion dollars out of the reach of the banks every day.

The result will be further “emergency lending” from the Fed necessary to counteract its own policy. With one hand, the Fed will expand its balance sheet through discount window and BTFP lending, while its other hand attempts to shrink the balance sheet via QT.

Fortunately, we pose a solution.

“Operation Squeeze”

The Fed is simultaneously borrowing $2 trillion from money market funds, while lending $392 billion to banks. It’s as if the Fed is holding a plug and staring at a socket wondering what to do. The best solution is the simplest: forcibly reunite money market funds and banks. Plug them back in.

Currently, RRP usage is driven by economic incentive. Since T-bills are trading well below the RRP interest rate, balances won’t decrease on their own. Rather than adjusting the award rate or hoping the RRP will decline on its own, the Fed could simply reduce the counterparty limit, currently set at $160 billion per entity9.

By reviewing the current RRP usage by entity, the Fed could reasonably estimate the cash flow effect of any given counterparty limits, and target a level that offsets the liquidity drain of QT10. The cash that is squeezed out of the RRP would re-enter the banking sector.

As an example, below is the RRP usage by the largest money market funds as of the end of February11, as well as the implied benefit to bank liquidity if the counterparty limit was reduced.

If implemented correctly, Operation Squeeze would allow the Fed to continue its overall pace of QT, shrink its balance sheet, while also improving or maintaining bank liquidity.

The benefits are obvious. It would support financial stability by gradually re-connecting the wires that the Fed unplugged in the first place. The Fed would not have to explain how massive surges in the Fed’s balance sheet is “ACKSHUALLY NOT QE”. While savvy observers may reasonably suggest that Operation Squeeze is a form of stealth QE, it could be easily branded as a technical tweak. Over time, the Fed may actually succeed in shrinking its balance sheet.

There are also drawbacks. A restriction on RRP usage would weaken the facility’s power as an overnight rate floor. T-bill and broad repo rates may fall below the target range - undercutting the Fed’s rate policy12. The influx of cash into banks would likely reinvigorate financial markets by giving both banks and non-banks more liquidity to play with. Other things equal, it would be inflationary.

But, as argued above, if the key driver of money supply growth was QE rather than credit expansion in the first place, then perhaps the inflationary impulse is of less concern. Under the current path, the Fed will be forced to pump newly printed liquidity into the banks anyways.

Conclusions

Interest rates alone cannot explain modern monetary policy. Today, QE and QT play outsize roles in money creation and destruction, inflation, and financial stability. At a minimum, we must refocus the public’s attention on these issues.

Operation Squeeze represents an elegant and obvious solution to the liquidity concerns that we have highlighted and repeated since QT began last year.

Now, how likely is it to occur? Not very.

For one, the Fed still has yet to acknowledge there is a problem with QT. Second, the Fed’s intuition is to solve problems by expanding its own reach by inserting itself ever deeper into private markets (this is how this problem started). By contrast, Operation Squeeze would eliminate the Fed’s new role in money markets and force private actors to play with each other once again. For this reason alone, it may be dead-on-arrival.

But in the past two weeks, the Fed has given us 392 billion new reasons to doubt its wisdom.

If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, please subscribe, hit “like”, and tell a friend! Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

As always, thank you for reading.

-TLBS

Japan is the classic example used to argue “QE is not inflationary”, since inflation remained low despite a longer history of QE. But money supply growth in Japan has been below 5% since 1991 - their QE has merely been used to offset flat to declining credit growth. Back when Japan increased money supply by 28% in 1972 (comparable to M2 growth in the US in 2020-2021), inflation spiked to 25% in the following years. Japan, ironically, actually makes a strong argument for the significance of money supply on inflation.

Bank lending briefly expanded at the beginning of the Pandemic as companies drew on existing credit lines (i.e. committed but undrawn facilities such as corporate revolvers), but those sums were quickly paid down by mid-2020. Ignoring this temporary spike, overall bank loan balances remained flat for much of 2020 and 2021. Lending began to accelerate as the economy continued to recover and expand throughout 2022. Yet, the pace of loan growth clearly peaked in mid 2022 and has been decelerating since the Fed began its jumbo rate hikes.

This is incredibly unusual. Money supply rarely ever shrinks, and is often associated with depressions. The only reason why the Fed is now shrinking money supply is to try to retroactively undo their largesse from the prior years.

Of course, inflation is complicated. Fiscal policy took the new printed money and distributed it to checking accounts, resulting in a much quicker transmission to real economic activity and inflation.

Higher interest rates will discourage borrowing today and will help slow inflation. That may be necessary and appropriate. But the net effect of credit expansion in recent years pales in comparison to the direct impact of QE/QT on the money supply.

Loan growth is higher quality, more sustainable and economically beneficial form of money growth than QE since it is specifically underwritten against new productive assets.

Similarly, flows into money market funds are not problematic by themselves. The trouble comes when those money market funds park funds in the RRP instead of banks. In other words, the availability of the RRP as an alternative to private counterparties is the underlying problem - not the absolute size of money market funds.

When ignoring the QT that effectively passes-through the TGA. Further, the TGA will soon become a drain on bank liquidity after the resolution of the debt ceiling allows the Treasury to begin issuing new net debt again.

In September 2021, the counterparty limit was doubled from $80 billion to $160 billion. The total uptake is $2.2 trillion, spread across 99 counterparties or an average of $22.5 billion per entity.

The Fed could make a one-time change to the counterparty limit, as it has in the past. Or if the Fed wants to provide extensive forward guidance, as it tends to prefer, it could lay out a long term schedule - i.e. the counterparty limit will be reduced by $10 billion per month for the next 16 months…

Data per the Office of Financial Research as of the end of February. More recent data shows that RRP uptake has increased significantly in the past several weeks. For example, Fidelity’s Government Money Market Fund’s latest data shows that they have now reached the $160 billion cap, representing 72% of their total assets.

If a sneaky Fed really wants to effectively cut rates without actually cutting rates, this is a pretty perfect way to do so.

A bit off-topic, but I asked GPT-4 for a one paragraph summary of your last three posts:

In a series of posts, the author discusses the issues surrounding the U.S. financial system, highlighting the impacts of Silicon Valley Bank's failure and the subsequent actions by the Federal Reserve. The author argues that the Fed's focus on interest rates rather than balance sheet policy has left the financial system vulnerable to liquidity stress. Since the pandemic, Quantitative Easing (QE) has driven money growth, while Quantitative Tightening (QT) is now causing liquidity problems in the banking sector. To address these issues, the author proposes "Operation Squeeze," which involves forcibly reconnecting money market funds and banks by reducing the Reverse Repo facility counterparty limit, allowing the Fed to continue QT while maintaining or improving bank liquidity.

I, for one, feel like I have no choice but to welcome our new AI overlords

"The best solution is the simplest: forcibly reunite money market funds and banks"

That mechanic is already occurring naturally through the FHLBs. Why did RRP significantly drop 3/9 -> 3/14? Because FHLB issued a couple hundred bil of debt (to fund advances to probably mostly smaller banks looking to replace fleeing deposits). MMFs bought that debt (at the expense of RRP). Of course RRP has risen again since due to the inflows of new deposits/reserves into MMFs (117b last week) overwhelming any reallocation from RRP to FHLB debt

Mechanics aside.... I heartily disagree that there are too few aggregate reserves in the system, even when you just look at bank reserves (excluding RRP). Before SVB and the deposit runs on smaller banks there were 3T in bank reserves (~3.4T today). In Sept of 2019, when system legit snapped imo due to lack of aggregate reserves (given regulatory intraday liquidity constraints etc.) there were ~1.5T in aggregate reserves (and 0 in RRP). Sure, 30% money growth since then but also some auto-reserve printing capabilities like SRF as well. Anyways we shouldnt need x2 the bank reserves (again not even considering the 2.2T reserve tank we also have in the RRP). Bottom line, its not an aggregate reserve problem imo, its a deposit/funding problem for banks with problematic asset profiles and a collapse in trust from their depositors (particularly their uninsured ones) intermixed with a desire of those depositors to not get basically 0 on the bank deposits in excess of their operational liquidity need.

Regardless, still love this article and how it explains the setup, just disagree with what i think is a fundamental premise behind your conclusion and thought you might find my perspective thought provoking.

Anyways keep up the great work! It is much appreciated.