So-Fried

The consumer is weakening and so is its lender of choice.

By: Daniel Saedi, Former Banks Investor at Bridgewater and Founder of Minerva, and The Last Bear Standing.

The Saedi Summary

Social Finance or SoFi (SOFI), once a silicon valley success story leading the DeBank movement, has transformed into a regulated specialty consumer lender with all of the same challenges and significantly worse positioning than its new competitors.

In the past three years, SoFi’s business model has shifted dramatically — from high quality student loans to unsecured credit card consolidation and personal loans. An OCC bank charter has allowed for cheaper funding and faster growth, but the company continues to count its profits as if it were simply an originator, not the loan-to-hold bank model it has largely adopted.

By valuing its balance sheet loans well over par — an unusual and aggressive accounting practice — SoFi front-loads its earnings and equity capital accretion. But this aggressive approach also brings mark-to-market volatility with immediate impact on its financial and regulatory standing. Today, nearly a third of its tangible equity capital has come through the cumulative write-up of its loans, even as its credit performance has materially declined. If it were to value its loans at cost with reasonable credit loss assumptions — like all of its peers — SoFi would likely trip bank capitalization requirements, prompting immediate corrective action.

What do you get when you have an undercapitalized, fast growing bank making riskier and riskier loans? History has never been kind at the end of a credit cycle to these players, why should this time be different?

Don’t Bank. Sofi.

“We see ourselves as a technology platform... not beholden to the same constraints as a bank.” - Mike Canegy, Former CEO

Social Finance has been one of the Silicon Valley darlings of the 2010’s fintech revolution. Founded at Stanford in 2011, it began as a student loan refinancer and eventually became a private student loan originator, following the success of peer-to-peer lending startups like Lending Club. SoFi benefited from the FinTech and SaaS craze in the valley at the time, with a bombastic CEO who insisted during the run up that SoFi was a technology platform, not a bank. All across San Francisco, and eventually even Wall Street, during the 2015-2017 era, you could find their marketing slogans like “Don’t Bank. Sofi” and “Even banks don’t want to be banks anymore”.

But what was so special about SoFi, and how was it able to distinguish itself from existing peer to peer players like Lending Club, consumer focused BNPL fintechs like Affirm (at least early) and tech enabled originators like Rocket? Brilliant distribution, a focus on a safer but fast growing segment of the consumer lending market in private student loan refinancing from top institutions and graduate programs, and an inability of older consumer credit models to incorporate income curves and growth for that market.

Back in 2015, with capital cheap and a good story, SoFi was off to the races. It made sense for someone with an MBA from Stanford or Harvard to consolidate their federal undergraduate and graduate loans and get some extra cash to spend at a 3% secured interest rate.

In an era of growth at all costs, SoFi was able to effectively turn cheap debt capital from loan hungry banks in California like East West into its customer acquisition tool. It may seem like forever ago, but companies back then in its cohort of West Coast upstarts were selling useless products at massive losses while wasting equity capital on ineffective marketing campaigns plastered across the internet. At one point we even had a company that promised to send somebody on a scooter to valet your car for cheaper than it was to park on the street.

SoFi was able to flip this model on its head and use ZIRP directly, lending at very thin net interest margins (NIMs) and packaging up loans whenever it needed cash or liquidity. The result? Nearly $3 billion in total capital raised from funds like SoftBank, IVP and Discovery before Chamath took the company public via SPAC in 2021 at a $9.5 billion valuation.

Despite proudly claiming that not even banks wanted to be banks, Sofi eventually became attracted to the prospect of consumer deposits vs. expensive shadow bank financing and acquired a national banking charter through the acquisition of Golden Pacific Bancorp in February 2022. SoFi became the very institution it was trying to displace.

What Happens When a Silicon Valley Darling Becomes a Bank?

Every bank is a company. But not every company is a bank. Once you obtain a bank charter and fall under the purview of the Federal Reserve and OCC, it doesn’t matter if you were funded by Founders Fund, Softbank and QED, you are now more similar to the small mechanics bank in Gary Indiana than you are to OpenAI and Facebook.

As someone who has covered and studied banks for nearly two decades, studying credit cycles going back to the Roman Empire, there is one constant, timeless and universal phenomenon that emerges — somebody always thinks that they can lend better and begins to issue new credit quickly. Usually, they’re actually a bit better than the incumbents at the start of the cycle, but once their perceived edge starts to dry up or they fall under pressure to keep the growth engine going, they make riskier and riskier loans.

This is a tale as old as time — and we see it here again.

While SoFi had an early edge in extending lower interest rates to qualified borrowers at premier educational institutions in the US, that edge and technology does not apply to unsecured personal loans and credit card consolidations, which now make up the majority of SoFi’s growth and loan book. No matter the data, technology, or AI advantage, consumer lending is a game of margins and there is a reason credit card companies extend 20-34% APRs to individuals who have 700+ FICO scores — borrowers default on unsecured loans first and recoveries are very slim.

With an originator model, SoFi would simply continue to borrow money from banks to issue loans to consumers and then turn around and sell those loans back to the banks or to asset backed securitization vehicles clipping the interest difference, origination fee, acquisition fee, and servicing fee for continuing to collect payments.

But if you think you are uniquely good at finding diamonds in the rough borrowers, you want to capture the full economic value of the Net Interest Margin (NIM) through time, which only makes sense if you are a bank. Why? Because banks can create loans funded by deposits, which are much cheaper than lines of credit, and they get to decide when they want to mark things to market or hold until maturity, allowing them to smooth their returns (I wonder where private credit got this idea from).

SoFi told investors that they sought out a banking charter to (1) be able to offer a larger suite of financial products, including saving and mortgages, to their customers and (2) to access deposit funding directly from consumers. It was a major step in fueling the growth engine that began to pay off even as rates were rising.

Despite the Fed hiking 525 Basis points from 2022-2023, SoFi’s cost of funding rose far more gradually as it switched from expensive warehouse financing from other banks and financial institutions to retail deposits.

But being a bank brings new levels of scrutiny. Governments have known that banks have the ability to create money for centuries and therefore have attempted to regulate them much more stringently than regular corporations. This burden has prevented many fintech companies from attempting to be true depository institutions.

Amongst a whole host of regulatory requirements (AML, KYC, liquidity, stress testing and capital planning), the most applicable across time and space has been capital and loss reserving. In the modern version of banking regulations that we see today, all regulated banks have to maintain minimum capital ratios. They need to have positive equity and that equity must be relatively liquid in the event that losses are sustained.

The Bank’s Books

Despite becoming a bank, SoFi still prefers to think of itself as an originator and distributor, not a balance sheet lender. While nearly all banks value their loans at amortized cost or “par” value with a reserve for credit losses (the Current Expected Credit Loss or “CECL”) approach, SoFi opts to value its loans on a “fair value option” — allowable under GAAP but highly unusual among peers.

The two methods result in dramatically different earnings and capital balances.

Amortized Cost Accounting: Under standard accounting, a bank does not “make money” in its P&L simply by issuing a loan. While the bank expects the loan to be profitable, it takes P&L earnings throughout the life of the loan as it actually performs.

When issuing a new loan, the bank will mark the loan at its amortized cost (or roughly “par” value), with a reserve for expected credit losses. Then, over time, the bank will recognize earnings through ongoing spread between the asset yield (interest received from the loans) and its funding yield (the cost of deposits). If the bank sells or securitizes a loan, it will record a gain or loss on the sale as it actually occurs.

In practice, this means that if a bank makes a five year loan, it will recognize the earnings throughout its duration. Likewise, the bank’s capital position will gradually grow as P&L earnings fall through to the retained equity. The bank can also update its credit risk over time through by adjusted the loss provision associated with the loan.

Fair Value Option: By contrast, a FVO approach effectively takes P&L credit for the loan on the day it’s issued. Instead of holding the loans at par value, the bank makes assumptions around prepayments, defaults, and a discount rate, which define the “fair market value” (FMV) of the loans it holds on its balance sheets.

Since a bank underwrites with the expectation of profitability, the FMV will almost certainly be higher than the par value of the loan, creating a day-one writeup in loan values. That writeup creates an unrealized gain that flows through the P&L and immediately accrues to the equity capital. Faster equity capital accrual also allows the company to grow faster without pressuring its regulatory leverage tests.

The FMV relies on management assumptions and dramatically accelerates earnings recognition and equity capital appreciation. While both methodologies are allowable under GAAP, the fair value option is aggressive and highly unusual for banks – in fact SoFi is the only bank of its peers that takes this approach for a majority of its loans.

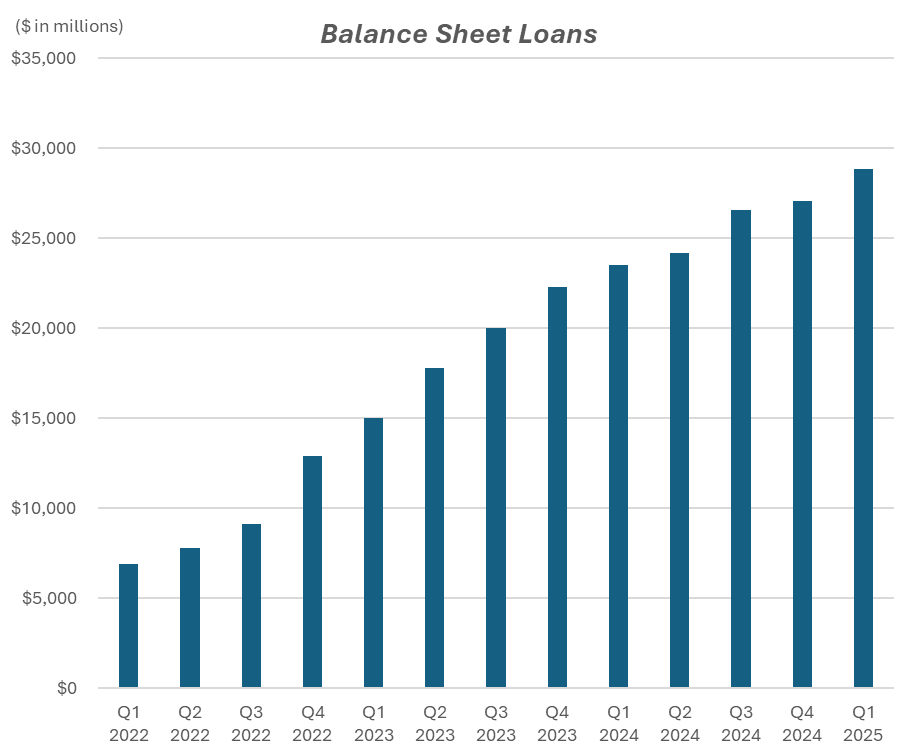

Simply, SoFi counts its earnings as if it were a pure play originator and loan seller, despite the fact that its balance sheet loan book has grown 4x in three years. SoFi wants the best of both worlds — it wants the valuation and reporting benefits of the write-and-sell model with the reliable and lower-cost funding of a bank. But with $27 billion in customer deposits, regulators might see things differently.

SoFi’s Marks

Below shows the key input into SoFi’s FMV marks by loan category; personal loans, student loans, and home loans.

Using these assumptions, SoFi’s personal loan book was valued at 105.5% of par value as of its most recent quarterly marks. In other words, for $100 of unpaid principal outstanding, the company has recorded an asset of $105.5. By contrast, CECL accounting would value these loans well below $100, when including a provision for losses. On average, companies like COF, DFS, and SYF value their on-balance sheet loans at ~$92.

While the company provides support for these DCF model inputs, it seems the real justification for auditors is by referencing the “Sales Execution” of its recent transactions. In the most recent quarter, the company calculated a personal sale execution level of 106.2%. In other words, so long as SoFi can offload some loans at 106.2, it can mark all of its balance sheet loans at 105.5.

Indeed, in its most recent investor presentation, SoFi shows the evolution of its reported sales execution and FMV over time, implicitly acknowledging the importance of these figures in justifying its balance sheet marks.

Again, SoFi’s guiding principle here is far more aligned with its shadow banking past rather than the regulated bank it has become. The entire valuation approach assumes efficiently selling loans rather than holding loans. Which is odd, considering the company now holds a whole lot of loans…

Capital Impact

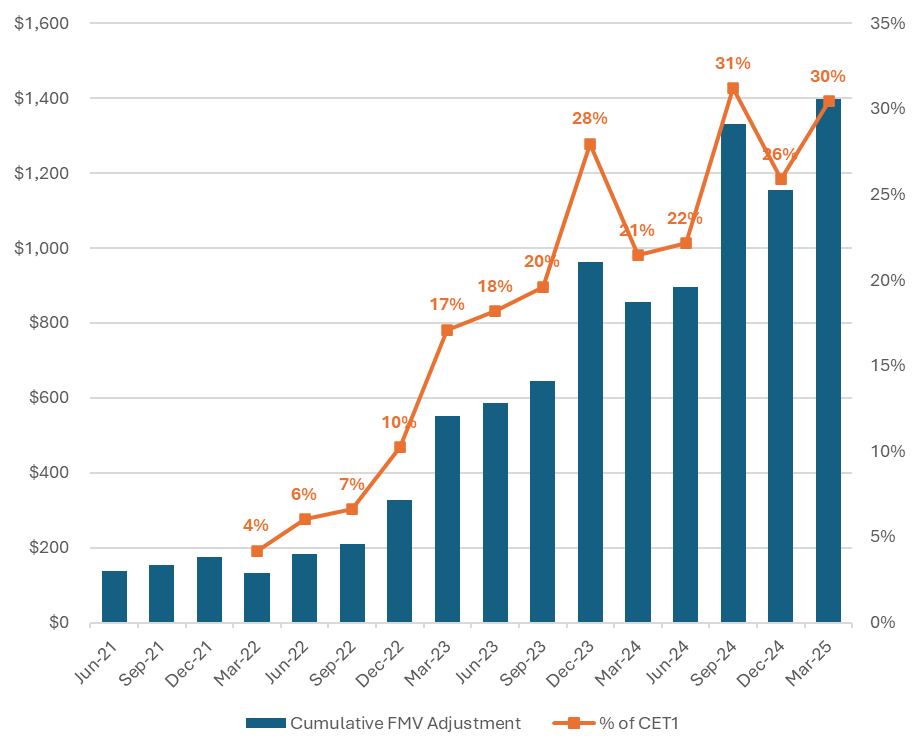

As spreads have tightened and sales execution has improved over the past two years, SoFi’s FMV markups has become an ever greater portion of its total reported profitability and, perhaps more importantly, its regulatory capital.

SoFi’s cumulative FMV adjustment of its loan book has grown to $1.4 billion as of 1Q25 — increasing both as a percentage of loans outstanding and regulatory capital. Today, this $1.4 billion markup constitutes 30% of the company’s Common Equity Tier 1 capital (CET1).

If SoFi was to hold its loans at par, the company’s CET1 ratio would fall to 10.7%, even before considering CECL loss reserves. If we assume a 5% CECL reserve, which is well inside SoFi’s 8% expected loss underwriting criteria for personal loans, the CET1 ratio would fall to 5.8%, well below the minimum capitalization threshold that would induce immediate regulatory action.

In other words, if SoFi simply followed the accounting practice of its peers, it would likely fall below the mandated minimum capitalization of 7%, triggering a Fed/FDIC’s Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) with an immediate halt on distributions and a formal recapitalization plan, backed by escalating supervisory oversight.

This question of accounting therefore is not trivial but critical. A reduction in these marks would materially reduce the bank’s equity capital, requiring the company to either dramatically reduce growth while building capital buffer or raise new equity which would be very negative for the stock.

And as we dig into the details, we see several causes for concern.

Things That Make You Go “Hmmm”

There are three red flags in the company’s FMV approach. We focus on the company’s personal loans, which are the largest – and highest risk – segment of loans. They are also the category held at the greatest premium to par.