Rate Cuts, Risk On?

#122: Rate Cuts and the Market, Reinflation Risks, and the Failures of the Fed.

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve officially joined the global easing cycle with the first rate cut in the U.S. in four years. Opting to kick things off with a plus-size 50bps cut, the Fed came out more aggressive than economist forecasts but well within market expectations which increasingly leaned towards a half-point cut as the meeting approached.

The committee notably eased its forward guidance by penciling in 50bps of incremental cuts by year-end according to its dot plots, implying a 4.4% federal funds target by December. This represents a significant shift in perspective from just three months ago, when the FOMC projected a year-end rate of 5.1% at the June FOMC meeting.

While the meeting tilted dovish, it still did not surprise the market which correctly interpreted the summer’s macroeconomic data. Short-term treasury yields have front-run the rate cuts since the tepid June CPI report put a final nail in the “higher-for-longer” narrative. With weak employment reports in July and August and a decidedly downbeat Beige Book release, full-employment clearly stepped in front of price stability as the primary concern.

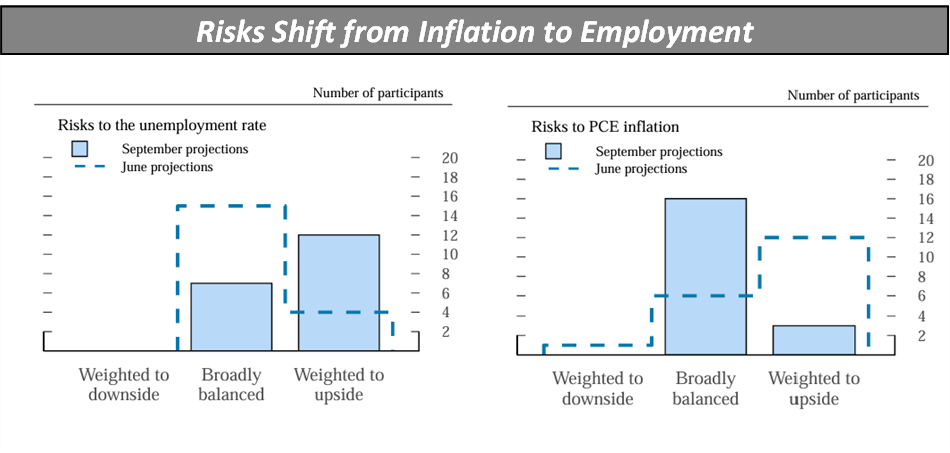

As shown in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), there has been a stark shift among the committee over the past three months from a focus on inflationary risks to unemployment risks.

In his press conference, Powell did his best to paint a picture of an economy that remained on course, while acknowledging the slowdown in job creation and notably even suggesting that payroll data — the brightest spot in the employment data — are likely overstated. Instilling confidence that more aggressive rate cuts are for good reasons not bad ones was a delicate task, but judging by the equity market reaction it seems that he succeeded. After a head fake on Wednesday afternoon, the market surged higher on Thursday as investors committed to the risk-on cue.

The S&P 500 pared its summertime slump, notching a new all-time high close with strength in both growth and cyclicals, with particularly strong performance in tech shares, industrials, and materials. Small-caps — the most levered companies with the highest direct sensitivity to interest rates — jumped over 2% on the day. Commodities have found a floor with oil, natural gas and non-energy minerals all up on the week. Gold continued its impressive ascent, posting a new record close.

Still, we are left with questions:

Are rate cuts really good for the market or are we overlooking macroeconomic weakness?

Could rate cuts reignite inflation?

How should we judge the Fed’s monetary policy in this highly unusual decade?

The Wrong Question

The million dollar question in markets is whether rate cuts are a good thing or bad thing. Many point to 2001 or 2007 to argue that rate cuts precede pain for the markets.

Detractors will claim recency bias and suggest that on a longer lookback rate cuts have generally been good for the market, particularly when the impetus for higher rates was inflationary pressure. One might cite data like the below table published by Morningstar yesterday which suggest that the market often performs well in the year after rate cuts, and that 2001 and 2007 are anomalous.

But the truth is that monetary policy was implemented in a totally different fashion in the 1970s and 80s. The federal funds rate was adjusted far more rapidly and with much more variability compared to modern days, without warning or transparent communication. Of course, there were no large scale asset purchases or sales via Quantiative Easing or Tightening. (When looking at the effective federal funds rate in those decades, one may be confused with how exactly Morningstar even tabulated the table above credibly, given the constant see-sawing of the policy rate).

Further, the current practice of extensive “forward guidance” via dot plots implemented in 2012 — where rate cuts can be signaled years in advance — clearly impacts the market’s reaction function, making comparisons to any of these prior periods tenuous at best. As I’ve written many times before, peak “monetary tightness” in the most recent rate cycle occurred in late 2022, precisely the moment that the Fed began to show a downward sloping curve its guidance. The market has appreciated 50% since, suggesting that some rate cut benefit has already been taken.

Instead, what has been remarkably consistent across decades is that the market declines during recessions.

In a cyclical macroeconomic downturn, the benefit of rate cuts pales in comparison to the effect of a recession on earnings, employment sentiment etc. And recessions are almost always defined by contraction in employment.