Is the Fed Broke?

#33: On the Fed's losses, Treasury remittances, and implications for policy.

Have you heard? The Federal Reserve is losing money.

Well, not really - the Federal Reserve can create as many dollars as it wants - rather, the Fed has negative earnings. What does this mean and does it matter?

Let’s dig in.

Income and Expenses

The Federal Reserve today looks more like a traditional “bank” than ever before. A consequence of post-Global Financial Crisis monetary policy is that the Fed now has meaningful interest income and expenses, and consequently, earnings and losses1.

Over the past decade of quantitative easing (QE), the Federal Reserve has amassed an enormous quantity of Treasuries (USTs) and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) from the private sector.

While the primary purpose of QE is to create easier financial conditions by injecting new money into the financial sector (i.e. lowering interest rates, increasing money supply2, and improving market liquidity), a secondary consequence is that the Fed accrues an enormous portfolio of interest-bearing securities. As interest payments are made by borrowers (the US Treasury in the case of USTs and homeowners in the case of MBS), the money flows to the Fed as “income”.

The Fed also has interest expenses. Since late 2008, the Fed began paying out interest to commercial banks on their reserve balances at the Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) rate - effectively the overnight policy rate of the Fed3. The introduction of the Reverse Repo facility (RRP) created another interest-bearing liability of the Fed.

When the Fed earns more interest income from its portfolio of UST and MBS than it pays in interest on bank reserves and the RRP, it has positive earnings. If its expenses exceed its income, it has negative earnings.

The Fed’s net earnings or losses are a function of the quantity and rate of its interest-bearing assets (UST and MBS), and the quantity and rate of its interest-bearing liabilities (bank reserves and RRP)4.

But such calculations have been largely unnecessary…until now.

Remittances

Historically speaking, the Fed has had positive earnings since 1915 - the income it generates from its portfolio of securities has always exceed its expenses. But of course, the Fed has no need for earnings - after all, it can create new dollars at will.

Instead, the Fed sends its net earnings to the US Treasury in a process called “remittances”. In other words, the net interest income that the Fed earns on its QE portfolio subsidizes the US Treasury and government spending.

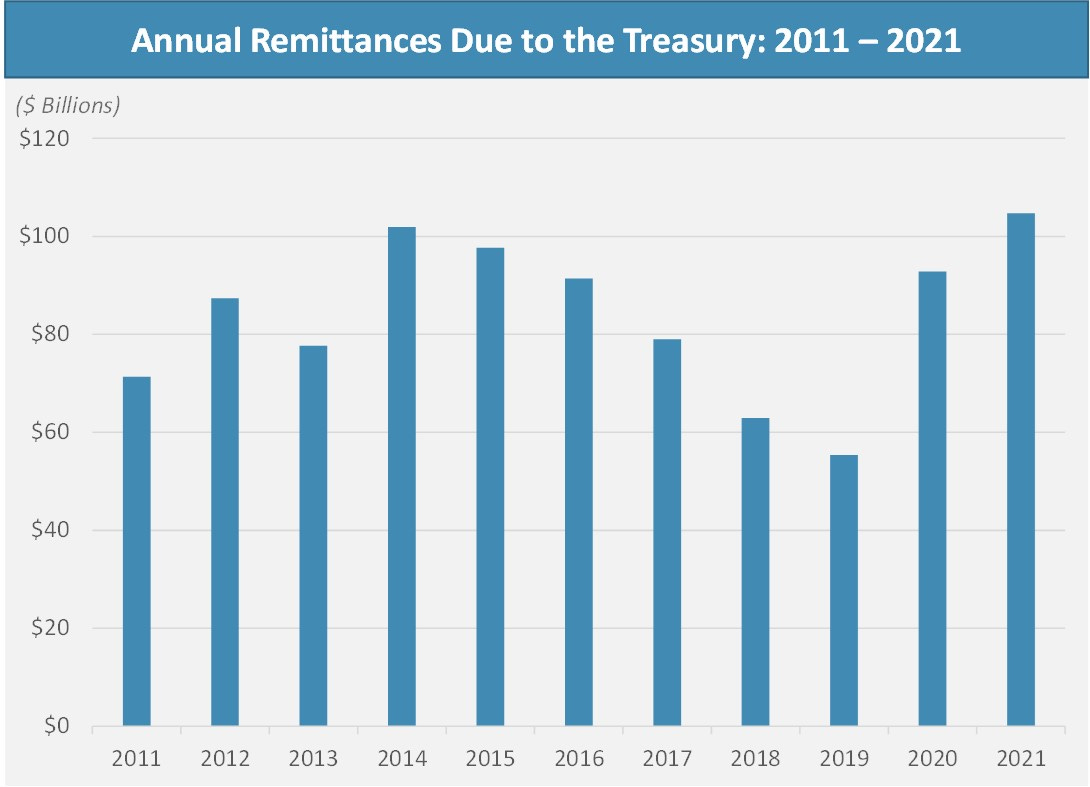

Remittances increased significantly in 2011, shortly after the Fed began its first phase of post-crisis QE. Since 2011, the Federal Reserve has sent on average $85 billion to the Treasury annually, totaling nearly $1 trillion through August 2022.

While remittances are not huge in any given period, they have been a consistent source of funding for the Treasury and have reduced the need for new UST issuance. By rough calculations, total remittances have offset 7% of the aggregate federal deficit from 2011 - 2021.

Significant remittances have been a quiet and underappreciated perk of the QE era. But, this perk has ended.

Into the Red

In September 2022, the Fed’s net interest income turned negative, due to a mismatch in the structure of its assets and liabilities.

The Fed’s portfolio holdings of UST and MBS have fixed interest rates. Meanwhile, the interest expense it pays is variable, fluctuating with the Fed’s short-term policy rate.

As the Fed has aggressively raised interest rates from near-zero in March to 4.3% today, the interest expense it pays to commercial banks and RRP participants has exploded higher. Meanwhile, the size of its fixed-rate portfolio shrinks with quantitative tightening (QT)5.

This combination has created the following Chart of Doom, which you may have come across in financial media or on Twitter.

But this chart6 is a bit misleading and counterintuitive.

First, remittances are a one-way street. If the Fed has positive earnings, it remits the earnings to the Treasury. But if the Fed incurs losses, the Treasury isn’t required to cut a check to the Fed to cover those losses. Instead, the Fed “prints” the difference. It simply pays the excess interest expense with newly created dollars7, in the same way that it prints dollars to buy bonds in QE.

The Fed keeps track of its cumulative losses, and when the Fed starts earning money again in the future, it will first go to recoup those losses before remittances to the Treasury resume.

In other words, the positive balances shown in the graph above are in-period (since earnings are constantly swept to the Treasury), while the losses over the past several months are cumulative, since they accrue over time.

But more importantly, Fed losses are not a “problem” in a practical sense. Unlike a commercial bank, the Fed can’t go broke - it can always print. Therefore, the Fed’s losses are the private sector’s gains.

Specifically, more money is created and paid to commercial banks and RRP participants, increasing commercial bank capital and providing income to money market funds.

Ironically, this monetary stimulus is a result of the aggressive rate hikes of the Fed - and the higher rates go, the larger this effect will be.

Sizing the Hole and Implications for Policy

The trajectory of Fed losses will be primarily a result of the path of interest rates. Today, with the Fed paying 4.4% IORB on $3.2 trillion in bank reserves and a 4.3% rate on $2.1 trillion in the RRP, the total annualized interest expense of the Fed stands around $240 billion. Meanwhile, the Fed estimated its interest income for 2022 at around $150 billion, leaving almost a $100 billion annualized loss.

The loss will only grow to the extent that the Fed makes good on its intended rate hikes in the coming months, increasing its interest payments to the private sector, while income on its fixed-rate securities portfolio remains relatively steady.

Yet, in the scheme of things, these excess interest payment to the private sector will only marginally soften the effect of ongoing QT, which is slated to run at a cap of $95 billion per month, or $1.1 trillion annually for the foreseeable future. If the Fed wishes to totally sterilize the stimulative effect of its interest payments, it could simply increase the pace of QT to counterbalance.

Further, the negative impact of higher interest rates on financial conditions is likely to be far greater than the marginal benefit of higher income payments to banks and money markets.

The biggest loser is the Treasury, which will be starved of remittances for the first time. This will force the Treasury to issue more new debt to make up for the funding shortfall, at a time when treasury supply is already set to expand against the uninviting backdrop of QT. As the Fed’s accrued losses deepen, it will take longer and longer before the remittances resume, as the Fed’s earnings must turn positive and dig out of a big hole8.

Conclusions

So, no, the Fed is not broke, nor will it ever be. The effect of the Fed’s negative earnings is more money creation via higher interest payments to the private sector. While this imbalance is ironically the result of higher interest rates, the benefit is relatively small when compared to the negative impact those higher rates have on the rest of the financial market and the much larger liquidity drain of QT.

The Treasury, for the first time, will not have the Fed subsidizing its budget - and such funding is unlikely to resume in the near term. This makes the prospect of funding the government more challenging and comes as questions loom about the ability of the market to absorb new UST issuance.

In the meantime, noise around Fed “losses” are likely to be just that - noise.

As always, thank you for reading. If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, like this post and tell a friend! And please, let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

-TLBS

Technically, the Fed has always had earnings or losses, but they have become much larger and more variable as a result of recent policy.

To the extent that sellers of the securities are non-bank entities.

This change was a part of an overhaul of the banking sector and would require an entire separate post to detail. The short version is that the Fed wanted to move away from a system where banks were incentivized to hold as little cash as possible, and so it began compensating banks for the cash balances they were force-fed via QE and required to hold due to more stringent regulation.

For our purposes, we will ignore unrealized gains or losses based on changes in interest rates and mark-to-market bond prices. Since the Fed does not outright sell securities in QT, but rather retires them at maturity, the unrealized gains are not practically relevant.

The Fed’s portfolio only adjusts to changes in interest rates as securities mature and are reinvested at prevailing market rates. The weighted average maturity of the Fed’s portfolio is roughly 5 years.

And creates a “deferred asset” on its balance sheet.

As of July, the Fed’s baseline estimate was that remittances could resume by 2025, but those projections are already far out of date, as they predated the Fed’s jumbo-rate hikes over the past several FOMC meetings. Today, we should expect a much deeper cumulative loss, and a much longer pause, unless the Fed slashes rates in the near future.

As is your norm, excellent article. Particularly enjoyed your labeling the "Chart of Doom"

Point of clarity though. I believe the cumulative deficit is only 14.3b thus far (see table 6 Liabilities, Earnings and Remittances Due to the US Treasury from most recent H.4.1 https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20221215/), but perhaps I am looking in the wrong place. How did you derive the 48b number?

Thank you Bear! Another great writeup!