The hardest choices aren’t between good and evil. The hardest choices involve trade-offs between desirable but conflicting goals.

Optimizing in a complex system involves balancing risks and benefits across multiple poles, mixing apples and oranges (and bananas and pears) to create the tastiest fruit salad. While it is easier to pick a single goal and maximize at any cost, it is rarely the best decision. Absolutists will be disappointed.

When a global pandemic threatens the lives of millions, do you take extraordinary action to stall the spread of disease at any cost? How do you weigh public health against public education, civil liberties, and the ability to put food on the table? How do you weigh categories with different units of measurement, and does the optimal balance shift over time as costs or benefits become more clear?

At the heart of the Federal Reserve’s mandate is conflict - the dual (conflicting) mandate of price stability and full employment1. In normal times, this is a delicate balancing act.

In April 2020, with cratering GDP, near-zero inflation, and double-digit unemployment2 the optimal choice seemed obvious - do whatever it takes, at any cost, to avoid a depression. Double the monetary base, backstop private credit, provide blanket industry bailouts, and fund Federal deficit spending equal to 15% of GDP. The Fed seemed to have a single mandate.

And here’s the thing - it worked.

Contrary to the dire projections at the time, the recovery in employment, consumption, and GDP are best described as “V-shaped”. It’s unlikely that such a rapid recovery would have been possible without the extraordinary policy. The pandemic demonstrated that a single-mandate Fed paired with unorthodox fiscal stimulus can be very effective. It proved that helicopter money has a powerful first-order effect in stoking demand.

But the Fed was never a single-mandate bank. The risk of stoking demand in the midst of supply disruption is inflation.

Permanent Stimulus

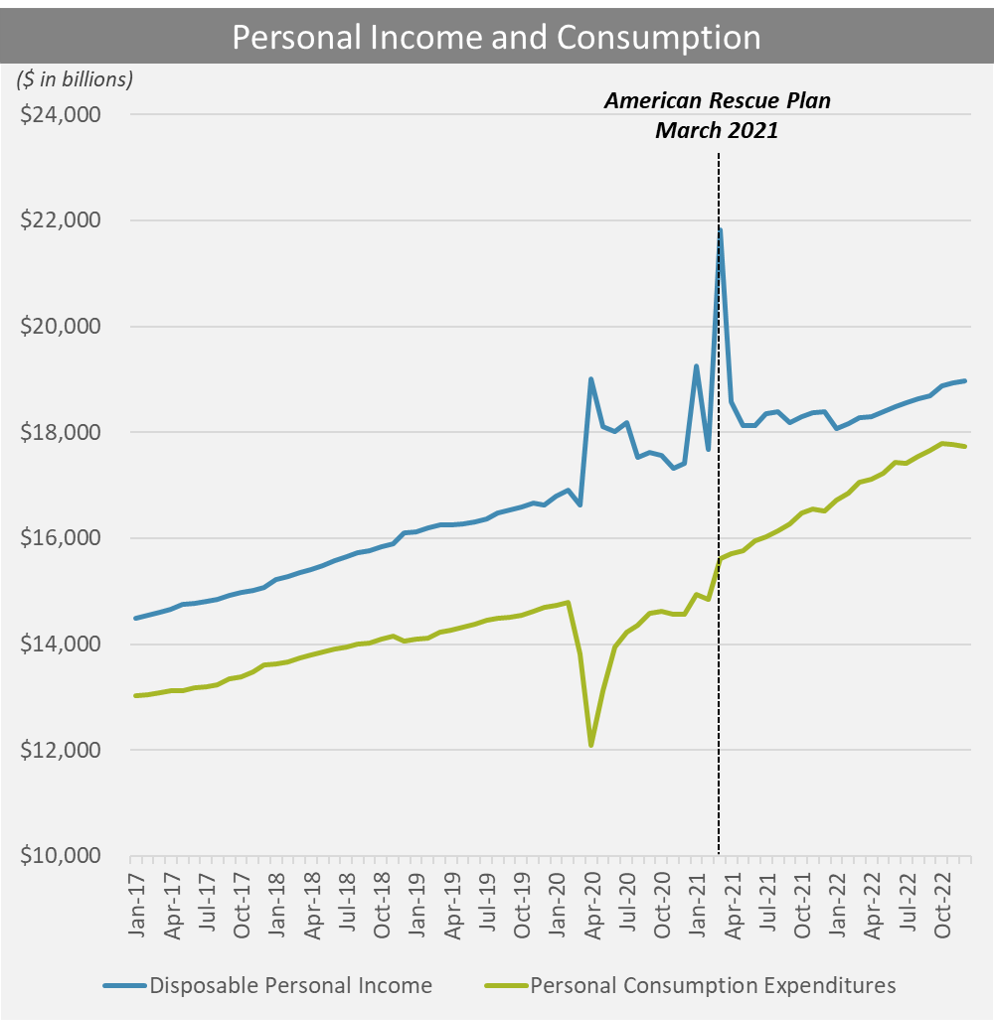

When looking at a simple time-series of personal income vs. personal consumption, we can clearly see how the timing and sizing of stimulus impacted economic activity. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) signed in March 2021 provided the final jolt in income necessary to bring consumption back to the pre-COVID trend.

The ARPA (and the preceding rounds of stimulus) was intended to jump-start demand, and it worked. Consumption returned to trend. But in order for the Treasury to fund such significant outlays, the Federal Reserve had to dramatically increase the supply of money.

In July 2020, the U.S. Treasury held $1.8 trillion in its account - more than the combined cash balance of every U.S. commercial bank just four months earlier. This was only possible due to the $3 trillion expansion of base money3 conducted by the Federal Reserve via Quantitative Easing (QE) in the first weeks of the pandemic.

The Treasury then spent its war chest back into the economy, injecting money into private bank accounts where it provided the support for the rebound in consumption and job creation. Each round of stimulus provided a one-time lift to personal income, but the cumulative impact was a step-change increase in money supply (regardless of which metric of money you prefer to measure).

Fiscal stimulus (when funded by new money creation) is not a one-time spending voucher. Rather, the dollars that were created to fund stimulus circulate and recirculate4. After its easily identifiable initial injection into the economy, “stimulus” simply adds to fungible cash balances and becomes regular old “money”. If there was a watermark on the dollars created during the pandemic, we could continue to track them and identify their ongoing positive impact on income, revenue, and earnings today5.

In other words, two years removed from the last major stimulus package, the economy is still benefitting from increased demand6. To the extent that productive capacity has not risen in proportion, prices will rise to fill the gap and bring the economy back into equilibrium.

So, was monetary expansion a policy mistake? It was a trade-off.

The benefits have been tangible. Real growth, consumption and employment rebounded faster than nearly any expectation. This is a good thing. The job market is remarkably competitive, household net worth has increased across all income cohorts, and businesses are generally still doing well7.

So, was monetary expansion a success? It was a trade-off.

The cost of artificially inducing demand is the inflation we are experiencing today. Inflation neutralizes the increased quantity of money by reducing the purchasing power of each dollar. Inflation is the constant, grating, drag of higher prices for all consumers. Inflation deflates the wealth boom of the pandemic.

The other cost of inflation is the fight against it.

Recent data shows the inflation battle is far from over8. In order to restore price stability, the Fed has slammed on the brakes to reverse the growth of money through higher interest rates and Quantitative Tightening (QT). Higher rates discourage organic money growth by reducing demand for credit, while QT directly sucks dollars out of the system. These actions are meant to reduce demand and economic activity, and typically end with both recessions and easing prices. If a recession is ultimately needed to tame inflation, then are we back to where we started?

Even then, there are arguments on both sides.

Was it better to kick the can down the road and forestall a recession until COVID had passed? Or, could the dramatic swing in policy over the past three years exacerbate a boom-and-bust cycle that proves to be more costly than consistent, moderate policy9?

That’s the problem with trade-offs - there isn't one correct answer and mistakes are often only obvious in hindsight10.

Tribes and Tribulations

There are those who have long argued for increased government spending, direct stimulus, and debt cancellation as a more direct and equitable method to spur growth. The COVID pandemic brought these views from the fringe to the mainstream and provided the opportunity (and monetary greenlight) to experiment with large-scale direct stimulus.

Meanwhile, others think that the Fed has enabled a growing and unsustainable federal deficit by suppressing borrowing costs and monetizing debt via QE. By backstopping financial markets at any wobble, central banks have established deep moral hazard as private risk is socialized and wealth inequality grows. Money printing is a well-worn treadmill that leads to inflation, the loss of faith in currency and institutions, and the demise of empires in the most extreme examples11.

Now, three years since the onset of the pandemic, we have experienced both a “V shaped” recovery in real economic growth and decades-high inflation. That’s the trade-off. Both tribes will tout their “wins” and obfuscate their “losses”, as they argue their preferred side of the coin - heads or tails.

In my view, we are still early in the game.

By acting as a one-mandate bank and increasing money supply to fund fiscal spending, the Fed created the conditions for a rapid recovery and a rapid increases in prices. Once inflation began to show up in the data in early 2021, it was outright ignored. More concerned with hand-holding the bond market than its mandate to maintain stable prices, the Fed held rates at zero and grew money supply via QE until March 2022. I suspect this will be regarded as a policy mistake.

Yet, the first order impact of monetary and fiscal stimulus proved to be an effective shot in the arm during a period of unique economic disruption. Is a great inflation better than a great recession? Without the counterfactual experience, we are left to guess. Now, we contend with the second order impacts - the nagging scourge of inflation, and the fight to end it.

Though it seems that moderate policy would lead to longer-term stability than a fishtailing Fed, wishful thinking doesn’t help explain or analyze the practical consequences of policy today.

We don’t yet know how long the war on inflation will last, or the collateral damage that will be left in the wake. Until these variables become clear, we are left waiting and pontificating.

Only with time can we grade the trade.

If you enjoy The Last Bear Standing, please subscribe, hit “like”, and tell a friend! Let me know your thoughts in the comments - I respond to all of them.

As always, thank you for reading.

-TLBS

Interestingly, Milton Friedman - the most famous monetarist - argued that there is not a conflict between inflation and employment over the long term. Though, in the short term, the two are linked due to the practical impact that unexpected changes in inflation have on business decisions.

One miscalculation was the failure to differentiate between the temporary and permanent effects of the pandemic. Mid-teens headline unemployment masked the fact that the vast majority of those workers only considered themselves temporarily unemployed. Similarly, the fall in headline GDP was due to imposed restrictions rather than a permanent contraction in activity.

“Base money” means dollars, in the form of physical currency or bank reserves.

This is why predictions that the economy would crumble once stimulus “wore off” have proven inaccurate so far. Stimulus hasn’t worn off - it circulates every day.

Because of the structure of the banking system, tracking specific dollars would be more complicated than if everyone simply held paper bills and traded them daily. But, if there was some unique identifier associated with each dollar (reserve or currency), plus a first-in-first-out (FIFO) inventory method for tracking inflows and outflows between commercial banks, I think it would be possible and interesting!

The term “demand” is in this context often misconstrued as people’s desire for things. I desire a penthouse overlooking Central Park, but unfortunately don’t have the money to purchase one. Demand is better understood as the desire and relative ability to purchase goods and services - a consequence largely of how much money you have to spend.

Corporate profits hit records during the pandemic. Even as margins have begun to compress, earnings remain near all-time highs.

This week was a double whammy as both consumer prices (CPI) and producer prices (PPI) bucked their recent downtrends. When combined with hotter than expected spending and jobs data, it is becoming clear that the disinflation party was premature. Though it does seem that all seasonally adjusted economic figures from January 2023 seem a little odd - perhaps a grain of salt is warranted.

Imagine if in the early days of the housing crisis - say early 2007 - the Fed slashed interest rates to zero and Congress signed COVID-sized stimulus. Presumably, there would not have been a recession in 2008, the housing market would have regained steam and equities would have risen. But, what happens a couple years later if inflation forced the Fed to hike rates even more aggressively on an even larger housing bubble? Of course we will never know the answer to this hypothetical.

Consider COVID policy. At what point did China’s zero-COVID strategy, initially lauded by many as a success, become widely derided as draconian lunacy?

The invocation of “hyperinflation” is usually either hyperbolic doomspeak, or a strawman argument to ignore the risk of inflation entirely. The U.S. is not the Weimar Republic, Zimbabwe, or even modern day Argentina. But sudden rises in inflation like we are seeing today pose a real economic challenge and should be taken seriously, even if prices aren’t doubling every day.

Hey Bear, an extremely balanced approach as always.

Something that is hard to prove or quantify in any way is whether the Fed has a third mandate, that of using its incredible ability to exert substantial influence over the global economy and use the USD as a means of applying pressure on other countries to align on its geopolitical goals.

During a period of liquidity withdrawal, with lots of EM in a tough spot I can imagine that swap lines can be a powerful negotiating argument.

I hope you get your Central Park penthouse one day. Thanks for another great piece!